"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

Thoroughly Modern Millie opened 50 years ago this week, in the spring between San Francisco’s Human Be-In and the Summer of Love. None of 1967’s Best Picture nominees, immortalized as the birth of the New Hollywood in Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution, had yet opened, but there was already something in the air.

Thoroughly Modern Millie opened 50 years ago this week, in the spring between San Francisco’s Human Be-In and the Summer of Love. None of 1967’s Best Picture nominees, immortalized as the birth of the New Hollywood in Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution, had yet opened, but there was already something in the air.

Director George Roy Hill capitalized on this countercultural moment with an extravagant show of concentrated nostalgia. Thoroughly Modern Millie leaps back to the Roaring 20s, America’s last moment of liberated sexuality and conspicuous consumption before the Great Depression. Its flamboyant, frenetic ode to the flappers and their world was a big hit, making more than $34 million and landing 10th at the yearly box office. The film was nominated for seven Oscars including Art Direction-Set Decoration.

Yet its portrayal is not without contradictions...

The New York City of Thoroughly Modern Millie is enlivened by its bright costumes and re-orchestrated hit songs, to be sure. But its production design hints at the falseness of this fantasy, even as it plays an equal part in the “madcap beauty.”

The most obvious example of this fakery is probably the sequence in which Jimmy (James Fox) climbs an office building. He’s in love with Millie (Julie Andrews) and is determined to wrest her heart away from her boss, the handsome and wealthy Trevor Graydon (John Gavin). And so he scales 20 or so floors of her quintessentially New York workplace, gleefully risking his life.

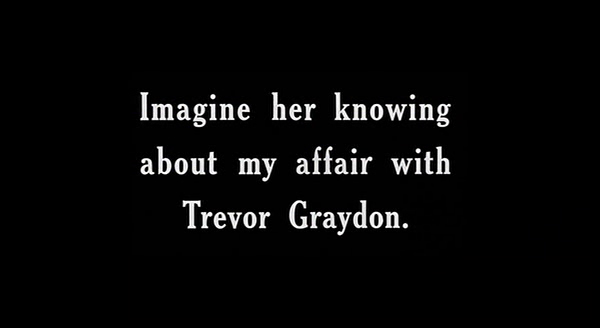

It’s right out of Harold Lloyd, and quite intentionally so. The scene places Thoroughly Modern Millie into the cinema of the decade, not its reality. Oscar-nominated set decorator Howard Bristol (Guys and Dolls) and art directors Alexander Golitzen (Spartacus) and George C. Webb (Sweet Charity) frequently allow a certain cinematic falseness in these sets. They fit right in with Roy Hill’s other nods to the silents, including the charming intertitles that function as Millie’s internal monologue.

This isn’t a total replication, of course, like Blancanieves. But there are periodic reminders of the charm inherent in silent cinema’s artifice. The finicky elevator is another example.

This same falseness is true of the romance, or lack thereof. Millie’s utter ignorance of her friends’ feelings turns every interaction into a clever farce. It also helps that even those moments that come closest to true love take place in front of such transparently painted skies as this one, behind a charmingly lit bridge.

Perhaps the most vocal romantic of the cast is Trevor, which is why he spends much of the last act of the film in a state of tranquilizer-induced paralysis. Dorothy (Mary Tyler Moore), who loves him, only adds to the comedy by not understanding the difference between bliss and unconsciousness.

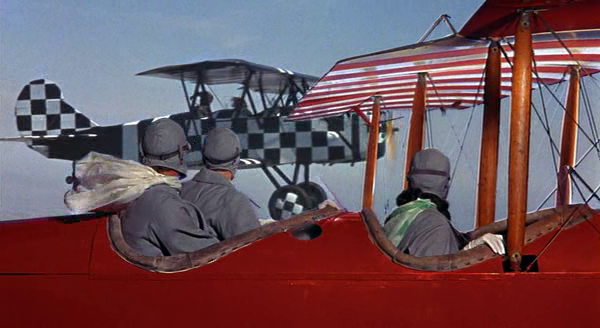

Besides, not one of these four lovers is the real life of the party. That would be the fabulous Muzzy van Hossmere, Carol Channing in her most iconic film role. She enters from above, in a ridiculous checkered airplane. Her pilot is German, a Red Baron who made it out of the Great War in one piece.

In fact, she surrounds herself with European expatriates. She performs with the Bernini Brothers, acrobats who also clearly reference World War One. Muzzy is like the Secretary General of her own League of Nations, ushering in a utopia built from jazz, world peace and raspberries.

Her mansion and its gardens would fit perfectly into the Long Island of The Great Gatsby, but without any of the crippling psychological downsides.

Thoroughly Modern Millie has little to say about prohibition, either. Its representation of 1920s crime is both comically absurd and profoundly racist. In the end, the “white slavery” ring run by Mrs. Meers (Beatrice Lille) becomes a punchline, another self-aware homage to the iconography of the silent era.

This subplot exposes two things about the film’s painted nostalgia. The first is on the surface, the continuity of Hollywood’s racist representation of Asian-Americans. The second is a bit deeper. The Roaring 20s, as represented here, may share some of the frivolity of the Swinging 60s. But there is a falseness even to this falseness, a misunderstanding of what cultural liberation really might mean. It hasn’t aged as well as those Best Picture nominees to follow for this precise reason, that even the charm of pre-Code Hollywood magic wasn’t quite freedom.

Other musicals in 'The Furniture':

Beaches (1988), Dreamgirls (2008), La La Land (2016)