Please welcome guest contributor Anna to discuss Gods and Monsters for its 20th anniversary. You can follow her on Twitter @MovieNut14

.

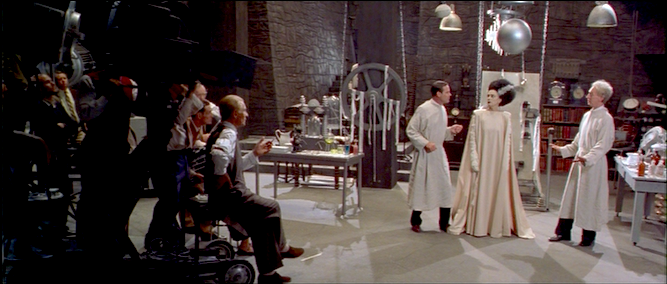

Based on Christopher Bram’s novel "Father of Frankenstein," Gods and Monsters – which references a line from Bride of Frankenstein – focuses on the final months of retired film director James Whale (Ian McKellen). Recovering from a series of minor strokes, he lives alone with his housemaid Hanna (Lynn Redgrave) and memories of his past. Because of his weakening state, he slips into a depression and contemplates suicide (which he would ultimately follow through in 1957). But the presence of gardener Clay Boone (Brendan Fraser) gives the aging man something to live for...

From my standpoint, the best works from director Bill Condon are those that focus on the matters of sexuality, a subject that he would highlight again six years later with Kinsey. And Gods and Monsters – its subject being the not-quite-open-but-not-quite-closeted Whale – is no exception. After all, Whale was alive during a time where such desires were not only frowned upon but also illegal in some parts of the world. (That doesn’t stop Whale from cattily gossiping about fellow gay director George Cukor’s sordid soirees nor his own past hedonism.)

From my standpoint, the best works from director Bill Condon are those that focus on the matters of sexuality, a subject that he would highlight again six years later with Kinsey. And Gods and Monsters – its subject being the not-quite-open-but-not-quite-closeted Whale – is no exception. After all, Whale was alive during a time where such desires were not only frowned upon but also illegal in some parts of the world. (That doesn’t stop Whale from cattily gossiping about fellow gay director George Cukor’s sordid soirees nor his own past hedonism.)

Being the first in a collaboration between McKellen and Condon – subsequent titles being Mr. Holmes, Beauty and the Beast, and the upcoming The Good Liar – Gods and Monsters began a professional union between two men that aren’t ashamed publically with who they are privately. And as stated before, their shared identities add a level of understanding to the film’s story as well as exploring how people like them had to hide behind a mask of normalcy to avert suspicion. The film is set during the era of Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter after all.

Gods and Monsters was certainly a shot in the arm for McKellen's mainstream career. (Roles in The Lord of the Rings trilogy and the X-Men franchise quickly followed this Oscar-nominated performance.) And though he lost to Roberto Benigni for Life is Beautiful (in fairness, it was a solid lineup of performances that year), one thing in particular stands out in the years since Gods and Monsters’ release: the rarity of having an out lead performer. It wasn’t commonplace for queer films to star actors of similar orientations (and to some extent it's still not) but McKellen managed to open a door (so to speak) not only for actors like him to play characters they can very much relate to but also to have them star in non LGBT related projects. The days of Anthony Perkins and Raymond Burr these are not.

Lynn Redgrave holds her own here as well. (Like McKellen, she earned an Oscar nomination for her work but lost to Judi Dench for Shakespeare in Love.) Her Hanna doesn’t suffer fools gladly but she remains loyal to her employer (even if she doesn’t generally approve of Whale’s homosexuality). But Redgrave – who died in 2010 – plays Hanna as more than your standard servant role; she has her own life outside of working for Whale.

During the 1990s, Brendan Fraser was quickly becoming an in-demand performer. But as the new century began to unfold, his popularity waned and the few projects he was involved with made him the butt of the joke, and often accused of only doing them for the money. Only recently have we learned why his career had suffered, the reason being one of Hollywood’s many dirty secrets. These revelations can make some moments in Gods and Monsters (the climax in particular) hard to watch. But that shouldn’t discredit Fraser’s work here; he shows he can hold his own against stage veterans McKellen and Redgrave. (And hopefully, Hollywood will give him a second chance in the coming years.)

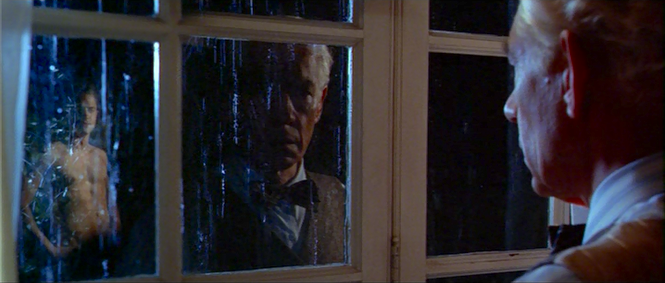

There’s an interesting manner in how cinematographer Stephen M. Katz frames a number of the scenes in Gods and Monsters. He captures Whale in a way that implies he’s already distant from the world he’s a part of. Long shots are used to achieve this effect, showing the empty space around the fading filmmaker. Many of his contemporaries have either grown distant or have passed on. Whale is trapped in his own little world, stuck somewhere with his memories and his desires.

Condon is adept at connecting Whale’s two worlds, his present and his past. Whale often finds himself reminiscing about his young upbringing or his career. But the event that stays with him the most is his involvement in World War I. (“Just like in the movies, only the movies now…they never get the stench of it all. The world reduced to mud and sandbags and a nanostrip of rainy sky.”) Just as they would do with Mr. Holmes seventeen years later, Condon and McKellen show how a once-great mind is far from immune to the effects of old age; the line between false memories and real ones gets fuzzier as one gets older.

Many things have changed in the twenty years since Gods and Monsters opened especially Hollywood’s attitude towards queer actors and stories. Audiences have developed more of an interest in queer stories. Queer actors have been given more opportunities than they ever could’ve gotten thirty years ago. (Granted, some of the more popular queer actors of today weren’t even alive thirty years ago let alone acting.) Gay audiences, too, feel more included with their stories being told. But when will Hollywood itself be completely accepting?

More on Ian McKellen

More Anniversaries

More on Oscars in the 1990s