This week, in advance of the Oscars, Nick Davis is looking back at the Academy races of 20 years ago, spotlighting movies he’d never seen and what they teach us about those categories, then and now.

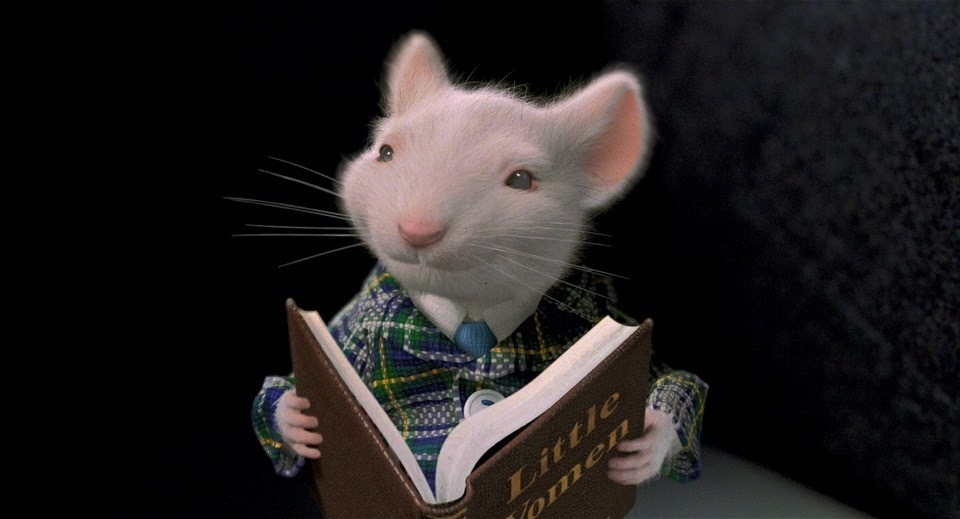

This year, The Lion King joins Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Kubo and the Two Strings (2016) as only the third fully animated feature to be nominated for the Best Visual Effects Oscar. I’ve read that tidbit in several places and assume that it must be true, according to people who know better than I do. I wasn’t sure why the movie that defeated Kubo, the 2016 remake of The Jungle Book, did not belong on this list, until I remembered that Mowgli was played by a living, breathing actor, Neel Sethi. Actually, what I mean is that I remembered Mowgli was in the movie, period. And I actually didn’t remember, I had to look it up. The Jungle Book, like an incredible number of films nominated for Best Visual Effects since the category got expanded to a five-wide field in 2010, made almost zero lasting impression on me. Like Best Original Song, it’s a division where I gladly release myself from seeing all the nominees. So, sorry, Lion King. Sorry, Endgame. Don’t get smug, Rise of Skywalker, you weren’t much better. And, until I proposed this series to Nathaniel, which partly exists to fill my own viewing gaps, sorry to Stuart Little, a movie that really tested my sense of the line between animation and visual effects, especially in the context of 1999. That line only gets blurrier as time goes on, so I thought I’d dig in a little...

I’m actually surprised I’d never seen Stuart Little, because I do have an abiding soft spot for cute, anthropomorphized critters on screen...as who, indeed, does not? I even read the book by E.B. White in advance of the movie’s Christmastime opening, right before I turned to its obvious companion volume, Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair.

As I’ve now discovered, the movie of Stuart Little resembles White’s book about as much as that little white mouse resembles his mom, Geena Davis (back in the Oscar mix this year as the Jean Hersholt recipient!). In the book, Stuart is the biological child of Mr. and Mrs. Little, even though they happen to be humans and he happens to be a mouse. A great deal of the book concerns Stuart’s attachment to a songbird named Margalo who briefly lives with the Littles but winds up fleeing for her life from a conspiracy of bird-thirsty cats. Stuart goes looking for her but does not find her. He is spurned along the way by a new love interest, Harriet Ames, when his big attempt to impress her goes haywire and he won’t stop pouting about it. He ends the book frustrated and alone, and the search for Margalo remains unresolved. As Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson discover when they read this book to wee Henry in Marriage Story, you can’t fully judge Stuart Little by its kiddie-marketed cover.

Despite his cameo in "Marriage Story," Stuart might be voting for Greta Gerwig's movie.

Despite his cameo in "Marriage Story," Stuart might be voting for Greta Gerwig's movie.

The screenplay for Stuart Little takes considerable liberties, though not the kind you might be expecting or hoping for when you notice that its co-author is M. Night Shyamalan (!!??), in the same year he broke out with The Sixth Sense. In this version, Stuart, voiced by Michael J. Fox, is the adopted son of the human Littles, played by Davis, Hugh Laurie, and Jerry Maguire tyke Jonathan Lipnicki. (You might call that a cursory detail, but the IMDb trivia page is an unwittingly hilarious exercise in concrete poetry, listing with identical phrasing the gajillion actors evidently "considered" for these roles.) I would not call the movie a high point in representations of adoption. Its big plot pivot involves Stuart’s birth parents, voiced by Jennifer Tilly and the late Bruno Kirby, showing up on the Littles’ doorstep and asking for their kid back. The Littles are glum about it, especially since their human son George has only recently started bonding with Stuart, but they’re like, “Hey, what can we do? They’re his ‘real’ parents!” And off he goes, that same evening. Damn, Littles! That’s cold as shit. I don’t think your ears were fully open to your adoption counselor.

But, no worries: Stuart comes back, in fairly short order. All the cats in the movie are devious, resentful monsters—even more so than in White’s vision, and to the apparent indifference of the effects artists themselves, who do pretty slipshod work in helping them speak convincingly. In any case, one cat has a moral conversion in sufficient time to facilitate the Littles’ reunion and guarantee their eternal happiness sequel rights, in which Margalo will finally come a-cooing. Meanwhile, there’s a near-disaster on a train set, a boat race, and a big washing-machine mishap, all of which is ...fine. The movie falls short of Paddington-style flair and exuberance, but not that short, and we have all gritted our teeth through shriller, less cheerful films for tots.

Stuart Little doesn’t over-stress itself with transitions between set-pieces. Even major character transformations happen rather fast, even by the standards of this kind of movie. As quickly as Stuart’s parents agree to give him up, for example, his birth parents elect pretty swiftly to out themselves as con artists, hired by those nasty cats. Plenty of people will appreciate the corresponding trimness of its 84-minute runtime except, perhaps, parents who hoped the movie might preoccupy their kids in the next room just a half-hour longer. I assume the reason here is the gigantic behind-the-scenes labor required for Stuart to do basic things: wear clothes, turn his head, react with shock or horror or delight. Forget about trying to steer a sailboat or brush his teeth or frantically keep his head above water during a perilous rinse cycle! The Oscar-nominated visual effects, then, are not just a proud plume on the movie’s surface but, I’d bet, an overarching factor that determined such things as length, narrative shape, and lighting. (I wasn’t wild about the cinematography by future Pan’s Labyrinth Oscar winner Guillermo Navarro, but I assume its hard, over-bright textures are helpful toward integrating Stuart into the overall mise-en-scène.)

All of the movie’s VFX tasks required meticulous collaboration with the animators, and thank goodness turn-of-the-millennium DVDs—when the format was still new, and bells and whistles could really move a disc through retail—are so good at explaining the difference. Individual commentaries on my copy of Stuart Little feature the testimonies of each department, and one set of featurettes invites representatives of both squads to demonstrate where CGI leaves off and animation picks up, though of course they all stress their absolute interdependence. The effects team, for example, devised 33 discrete facial expressions for Stuart, each calibrated down to its exact musculature; that’s still three fewer than Fanny Brice’s, but they permitted innumerable conflations for a wider variety of looks. Stuart can thus exhibit a whole spectrum of strength, fear, excitement, and exhaustion as he tries to power his brother's boat to a big racing win, while the animators decide how fast the captain's wheel should spin on that boat, and how much the painted cityscape-backdrop should tilt to imply Stuart’s degree of danger or control.

Stuart cycles through much of his facial repertoire while brushing his teeth on his first morning of life as a Little—basically a gratuitous mini-expo of just how mobile this tiny mouse’s mug can be. Meanwhile the animators add little droplets of water flying out of his mouth as he goes, and make sure that his clothes are bunching in all the right places as he leans toward the bathroom mirror or saws his arms back and forth.

In a further act of virtuoso show-offery, but also a tiny, plausible nuance that it’s great for audiences not to notice, Stuart’s little toothbrush even has a partially transparent plastic handle, as many of ours do; you can still make out the movements of his body through that translucent prism. The effects artists nailed down just how his toros and limbs should flex, contract, and operate while he brushes, thus avoiding any creepy, Cats-style floutings of proportion. And speaking of Cats, bear in mind that Stuart’s every major or micro movement entails corresponding shifts in hair and fur, a notorious trouble-spot for animators, which the Pixar team smartly sidelined from the first all-CGI animated feature by populating its story with plastic toys.

This tooth-brushing episode was part of the sequence that the artists on Stuart Little completed first, so the cast would have some idea of what their totally imaginary co-star would ultimately look like. Rehearsals, apparently, often involved a puppet stand-in for Stuart, but for most actual takes there was nobody there, not even a green dot. Maybe it occurred to you, but it wouldn’t to me, that even the bedsheets become visual effects in this context, since CGI artists have to determine how much Stuart weighs, and thus how much the pillow and the linens would depress beneath and around his body, especially with Mom leaning over to kiss him. I admit that detail-work in animation often strikes me as excessively, expensively obsessed with minutiae like this, which can start to drive the trains of story and character rather than the other way around. But Stuart is a winning little critter and seems impressively present and organic in his scenes—very hard to say about many 20-year-old CGI characters, even if compositing techniques, image-smoothing, and every other artistic effect deployed by this movie has evolved tremendously. In this way, as in every single other way imaginable, he blows fellow nominee Jar Jar Binks right out of the Gungan water, even if The Matrix, a movie I really responded to well in 1999, probably won this Oscar by one of the widest margins in Academy history. And deservedly so, as even I can grant.

Even as I try to disentangle the VFX work and the animators’ exact responsibilities on a project like Stuart Little, it’s worth pointing out that Oscar collapsed those things back together. AMPAS included animation supervisor Henry J. Anderson III as one of the movie’s four listed nominees on the Visual Effects ballot, along with effects supervisor and Oscar-winning Star Wars mastermind John Dykstra and his second-in-command Jerome Chen, who’d take over as department head on Stuart Little 2. This combined roster of nominees seems exactly right, considering the utter synergy required between those departments on such a film; Andrew R. Jones, the credited animation supervisor on The Lion King, is also one of this year’s Visual Effects nominees, along with three of his colleagues with VFX-specific job titles.

About Animation in 1999

So I’ll wrap this entry by noting that Stuart Little also belongs in the story of what an astounding year 1999 was overall for animated cinema in major U.S. release. Oscar wouldn’t inaugurate its Best Animated Feature category for two more years, and I’ve always assumed that the banner year that closed out the 20th century was a catalyst in making that happen. There is no question in my mind that if Best Animated Feature had existed in 1999, our contenders would have been these:

The Iron Giant, a commercial misfire but an immediate hit among critics and industry peers, and by now a widely beloved classic of hand-drawn animation, weighty in theme but tender in expression;

Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki’s still-timely masterpiece about factionalism, gendered notions of leadership, and eco-disaster, and the first Ghibli film to get a proper commercial release in the States, albeit on a two-year delay;

South Park: Bigger, Longer, & Uncut, a Best Original Song nominee and a new kind of watershed in screen musicals and in U.S. political cinema, addressed to contemporary figures and issues;

Tarzan, the Best Original Song victor and a perfectly sturdy entry in the Disney canon, with vine-swinging sequences that were pretty vanguard for the state of animated motion; and

Toy Story 2, the Golden Globe winner for Best Picture (Musical/Comedy), and one of many, many films that could and should have taken the place of the mediocre Cider House Rules or that shitpile The Green Mile in Oscar’s top category.

That list would have been a Hall of Famer, not just for Animated Feature but for Oscar ballots in general, as distinguished for each film’s individual achievement as for their collective range of styles, tones, genres, and themes. But even so, they are not the full story of how much film animation was testing its boundaries and tackling new challenges as the 21st century dawned. Stuart’s competitors in Best Visual Effects, The Matrix and The Phantom Menace, both include plenty of animators on their crews, as do many films that don’t seem obviously animated or effects-powered. The Green Goddamn Mile, for example, required animation work to help gift us all with Michael Jeter’s beloved little Lazarus mouse, who may or may not be Stuart’s distant country cousin.

And for all the forward-looking innovation you’ll see in 1999’s animated features, you can find equally brilliant valentines to old-fashioned styles in that year’s Best Animated Short category. Two exemplary contenders from that race are available on YouTube: Torill Kove’s My Grandmother Ironed the King’s Shirts, characteristically wry and adorable, and Aleksandr Petrov’s The Old Man and the Sea, principally voiced by Away from Her’s Gordon Pinsent and composed of 29,000 oil paintings on glass plates. Even here, boundaries of “old” and “new” are hard to draw strictly: The Old Man and the Sea was the first animated film conceived specifically for IMAX projection. In sum, every small step for sweet, fuzzy Stuart Little was part of a huge, eclectic series of giant leaps for turn-of-the-millennium animators and visual effects artists, who are not so easy to distinguish from each other even when you try.

P.S. About this year:

Writing this piece made me feel better about animated features and visual effects movies in general, since I find both of those ballots in this week’s Oscars to be very dispiriting. How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World, Missing Link, and Toy Story 4 all have plenty of bright spots, but their images, techniques, and stories feel broadly familiar in most respects. I Lost My Body takes a bigger risk with its premise and tone, but I find the execution pretty wonky (why does the hand...see??) and the storytelling pretty awkward, all the way from pacing to cross-cutting to gender politics. Klaus just ...anyway. Enjoy your weird BAFTA, Klaus. The three Visual Effects nominees I’ve seen, 1917, The Irishman, and The Rise of Skywalker, don’t exactly strike me as Academy-level achievements. But as you can hopefully see from my entry, I still have lots to learn in these areas, so if you want to make a swinging pitch in the Comments for something I’m undervaluing in one or more of these movies, go for it!