by Nick Taylor

Happy Holidays! We are celebrating a very dear, tumultuous season - awards season - and the current wave of critics prizes has left us with some very exciting developments. It’s perhaps not the biggest shock that Jane Campion’s austere, sensual Western The Power of the Dog has become such a critical darling. It’s the first time in nearly two decades that one of Campion’s phone is in serious consideration but the film’s remarkable showing with awards bodies and the sheer number of Best Director wins she’s accrued are both tremendously deserved and, given the overall trajectory of her career, something of a surprise.

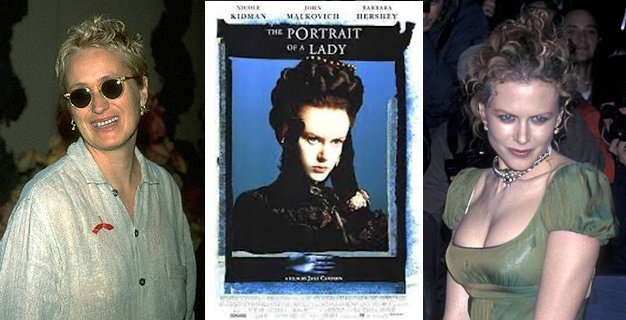

Releasing her first film since 2009’s Bright Star (and after showrunning the acclaimed series Top of the Lake for two seasons), Campion’s favor with the Academy and critics at large has shifted wildly over the years. As rapturously as The Piano was received, her 1996 bold, purposefully hard-edged adaptation of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady scuttered a lot of that goodwill, and as abrasive as that film is, I can’t for the life of me understand why this torpedoed her prestige reputation so badly...

I’m happy for the folks saying The Power of the Dog is a new peak for Campion, but anyone saying it’s a return to form hasn’t been paying attention. Maybe I’m waving my pom-poms in a small, dedicated corner, but I’m happy to wave ‘em here and now.

Before The Portrait of a Lady even begins in earnest, Campion disarms us in the opening credits. Multiple New Zealand women discuss their favorite things about kissing in voiceover while the production credits are listed. When the opening credits begin in proper, they become a montage of young women posing for the camera and dancing in a glade while the pan flutes of Wojciech Kilar’s score serenade them. It’s an unusual decision, an ode to the Isabel Archers of today as well as a fairly enticing dry run for many of the film’s aesthetic strategies. Stuart Dryburgh’s camera will remain fleet and mobile and gloriously attentive to the faces and bodies of the actors inside his impressive compositions, while Veronika Jenet’s editing keeps a tight hold on emotion and atmosphere, disrupting the camera’s ostentatious visual rhythms as often as she maintains them.

Without warning, the montage gives way to the actual film, shifting from a pan of the title written on a girl’s hand to a close-up of our intrepid heroine Isabel Archer (Nicole Kidman) as insects and birds drone around her, zooming in on her tear-stained face as her eyes dart in every direction, sometimes even spiking the camera. Her privacy is soon shattered in two ways. Cinematically, by the cut of the edit, moving into a medium shot that reveals she’s sitting on the branch of a tree that’s very close to the ground, while the rest of the tree shields her from the sun. Physically, by the approach of a man who we will learn is an artistocrat named Lord Warburton (Richard E. Grant). He seems a bit shell-shocked when he finally talks to her, reassuring her that if she doesn’t want to live at a particular house he owns, she wouldn’t have to, even if it is perfectly safe. He jokes that some people don’t like moats, and Isabel, desperate for any note of validation or kindness to give the man, says she likes a good moat, which becomes the signal he needs to reaffirm that he has been touched for life by her and will remain favorable to her, should she change her mind. This in turn becomes her signal to leave, departing from what turns out to be a very sizable garden hosting a small, intimate gathering and storming into a mansion without talking to anyone. Well, she talks to the dog, and hoists him up in a fantastic canted shot before she fully retreats.

James’s novel contextualized this encounter with sixteen prior chapters of introduction, characterization, and buildup, all of which is completely expunged from Laura Jones’s screenplay. Still, at what point in Isabel’s conversation did you intuit that the soft-spoken man she was talking to was a suitor she had rejected moments earlier? Were you keyed into this through performance? Lensing? Direction? Dialogue? Silence? All and none of the above? Throughout The Portrait of a Lady, Campion drops us in the beginnings, middles, and ends of complex interpersonal relationships and asks us to catch up to the histories of the people on screen while attuning to scene-specific emotional beats and the thick air of storied, not entirely knowable lives that clings to every character. It takes no time to become familiar with the color, temperament, and ambition of these figures, yet the mysteries they hold remain as proudly hidden as they want.

Speaking of mysteries, I should take a moment to establish the key relationships that the early sections of The Portrait of a Lady are built upon. Isabel Archer is a young American woman who’s been living with her American aunt Mrs. Touchett (Shelley Winters) and English uncle Mr. Touchett (John Gielgud) for several months now. Isabel’s time spent living and traveling in Europe has given her a level of freedom she’s always desired, allowing her to cultivate eccentricities and ideas she’s eager to test against the world while still presenting herself as an independent traveler rather than a potential bride for the men she meets. This desire for freedom is the primary reason she turned down Lord Warburton’s proposal, as well as an earlier proposal from an American heir named Caspar Goodwood (Viggo Mortenson), though her friend Henrietta (Mary Louise Parker) fears Isabel’s headstrong desires will soon lead her into an unhappy marriage. The Touchett’s son Ralph (Martin Donovan) is a frequent companion of Isabel’s, though his consumption prevents him from traveling Europe as fully and regularly as she does. Ralph also harbors a deep love for his cousin that he’s elected to keep to himself, knowing her attitude about marriage.

Isabel’s life takes two sudden and near-simultaneous turns about 20 minutes into the film. Mr. Touchett has become gravely ill, and is expected to die soon. Ralph persuades his father to allocate part of his inheritance to Isabel, so that she can have enough financial freedom to be truly independent the rest of her life - provided she never know Ralph orchestrated this, of course. News of Mr. Touchett’s illness also summons an old friend to visit and comfort him, American expatriate Madame Serena Merle (Barbara Hershey), who takes an immediate and mutual fascination with Isabel after she walks in on this unexpected guest playing Schubert on the Touchett’s grand piano. The sudden inheritance of a great fortune and her newfound kinship with Madame Merle ultimately places Isabel in the attention of another wealthy American, widower Gilbert Osmond (John Malkovich), an unpleasant, often nasty recluse who spends all his time curating an art collection and preparing his daughter Pansy (Valentina Cervi) for marrying the kind of rich man he wants her to marry.

Even this is only enough setup for the first hour, before we get two time jumps, a handful of new characters, and some old ones with new designs on Isabel and the world she inhabits. For all its glades of women and excision of the novel’s first quarter, The Portrait of a Lady is a fairly straightforward adaptation of James’s narrative on a structural level, even as it imposed new ideas on the material. I don’t say this to make a dichotomy between the fidelity of Laura Jones’s script and Campion’s direction smearing her iconoclastic fingerprints all over the novel. Adapting James for the screen has proven a difficult enough proposition that Jones’s success at translating the novel for the screen is a genuinely remarkable feat. The script ensures all of James’s structural gambits, lush emotions, opaque mysteries, and period-specific idioms play on film, while leaving ample room for a talented, visually inventive director to fill in all the interiority, atmosphere, and unspoken motivations of Portrait’s characters and their environment.

There’s certainly nothing in the novel to justify the feverish, hallucinatory black-and-white short film in the middle of the movie that depicts Isabel’s falling in love with Osmond as she travels an exotic desert locale. Nor is there anything to prepare for the number of canted shots Dryburgh uses, though they, like his languid camera movements and attention to every flicker of the actor’s faces, communicate a lot about Campion’s characters and deepen our responses to them intellectually and emotionally. The audiovisual richness endowed by every artist involved gives The Portrait of a Lady lucid, perverse textures while preserving its most trenchant mysteries and critiques with fine-honed ingenuity. One could easily view its overwhelming craft choices as something wild and untamed, and maybe it is, but Portrait’s choices, equally florid and claustrophobic, have a very clear origin point guiding them.

Enter Jane Campion, who honors Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady while filling her interpretation to the brim with her own thematic and artistic experiments. I can’t think of a film of hers that’s this sprawling, this stuffed with characters and locales that all feel like central narrative engines whenever they appear. Campion is entirely disinterested in James’s juxtaposition of American values against the backdrop of European aristocracy. Meanwhile, her feminist sensibilities and ideas on autonomy and responsibility are different from James’s in key ways, as much a reflection of “modern” theory as her own fascinations. Isabel’s initial attraction to Osmond feels like a masochistic impulse rather than a duped innocent. For all Isabel miscalculates how dangerous Osmond is, Campion and Kidman repeatedly convey a protagonist who would rather be pushed against, even punished, than given the room to spread her wings the way she says she craves. As sympathetic as her plight undoubtedly is, Campion neither makes Isabel a pitiful object of abused Victorian morality or an anachronistic femininity worthy of a modern viewer’s scorn. Instead, The Portrait of a Lady is a prickly, insightful character study of a woman torn between thriving within a patriarchal system and letting it crush her.

It helps that the cast rises tremendously to the occasion. Kidman achieves a layered, paradoxical blend of intrepid, unlikely fortitude and tear-stained despair nearly a decade before Birth gave us that opera scene. She stands by Isabel’s impulsiveness and intellectual curiosity while carving out unique, vibrant relationships to her scene partners. Barbara Hershey’s Madame Merle may be an even more fascinating creation, and yet another example of Campion’s naked fascination with fierce, complicated, and self-destructive women. Blessed with the film’s most memorable introduction and tragic exit, her pauses are as voluptuous with history and purpose as any of her dialogue or expressions. Merle is both the woman Isabel aspires to be and the walking tomb that her most masochistic impulses will lead her towards, and Hershey negotiates this with an emotional legibility and presence of self that’s just astounding to witness. Martin Donovan’s observant, lovesick Ralph is just as magisterial a characterization as either of these women, and Campion’s marvelous scope makes even the most tertiary actor register as concentrated, three-dimensional interpretations.

Best of all, I think, is that The Portrait of a Lady’s many hard, charismatic, stifling edges all speak to Campion’s talents as a conductor and a collaborator. Everyone here is clearly working within her designs but also smudging their own fingerprints alongside hers. This is as much Nicole Kidman’s Portrait as it is Campion’s, as much Dryburgh and Patterson’s and Hershey’s and Kilar’s. I love that this story of one intrepid woman’s fatal miscalculation is also the story of a whole team of artists marshaling such a bold, singular, modern-yet-period vision of one of the most famous pieces of 19th century literature. We don’t get that every day, even in projects specifically designed to reinvent classics or test their audience’s ideas about what they’re watching. The Power of the Dog will never be my favorite Campion film, and if it brings her her long-deserved Best Director Oscar I’ll never say a word against it. But nomination #2 shouldn’t have been a long time coming, and to revisit any of her works is to know for a fact how long and how creatively she’s been challenging what cinema can do.

More on Jane Campion

More on The Power of the Dog