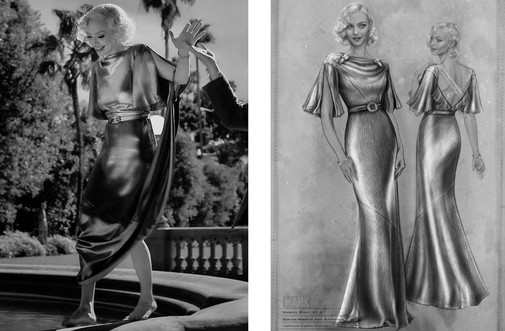

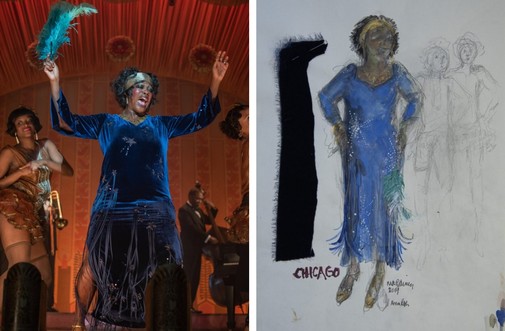

Costume illustrations by Gloria Young Kim (left) and Matthew JLeFebvre (right)

After last year's dispiriting domination of Best Picture contenders in craft categories, this year's Best Costume Design lineup feels like a breath of fresh air. While the branch is resistant to contemporary narratives, their reluctance to honor new names has alleviated a bit. For the first time since 2006, we have three first-time nominees among the costume designers competing for gold. Better yet, the five achievements honored by AMPAS offer a dizzying variety of film styles, aesthetic strategies, genre, and tone. From Disney remakes to Italian literary adaptations, from biopics to biting period comedies, this batch of nominees has it all.

Still, in the end, one must win. With that in mind, here's how I'd rank the five Best Costume Design nominees at the 93rd Academy Awards…

5) MULAN, Bina Daigeler

It's not often that one finds costume designers embroiled in controversy, but Disney's Mulan managed to do it. Even before the movie premiered on streaming, the production faced criticism for its lack of Chinese artists behind the cameras, namely the absence of a costume designer from China. Bina Daigeler was Nicki Caro's chosen artist (they previously worked together on The Zookeeper's Wife), a German designer who has worked primarily in Spanish cinema over the last few decades. In interviews, she has said it took her around three weeks to research the Tang Dynasty period (which is not when the original folktale is set), studying traditional Chinese garb from European museums in order to arrive at the stylistic intersection of historical influence and colorful fantasy that is Mulan's wardrobe.

First things first, denigrating Daigeler's work for its lack of historical accuracy seems beside the point. Her creations feature as much fairytale whimsy and unrealistic details as the majority of Disney remakes. Sandy Powell didn't set out to reconstruct accurate 19th-century European couture when designing Cinderella, nor did Anna B. Sheppard bind herself to the intricacies of Medieval garb when outfitting Maleficent. If anything, Daigeler's approach is closer to Jacqueline Durran's vaguely Rococo take on Beauty and the Beast. There's plenty of nodding towards history, but the main aesthetic is one guided by dreamy reverie than fact. All of those designers were nominated for the Oscar, just like Daigeler. Furthermore, a lot of the best Chinese period pieces aren't necessarily accurate in their sartorial choices. For instance, Curse of the Golden Flower is wildly stylized and earned an Oscar nomination for Chung-Man Yee.

That being said, it's not unfair to question the choice of designer. With a filmography that includes some of Pedro Almodóvar and Jim Jarmusch's most visually striking pictures, Bina Daigeler isn't a hack, nor is she necessarily a big name in the Hollywood industry. Mulan represents a huge swerve in her career, from auteur cinema to blockbuster entertainment. It also represents the costumer's first foray into ostentatious pre-20th century period wear. In that lack of experience lie the few glaring problems in her approach. The lack of accuracy isn't half as vexing as the questionable construction of some pieces, the eye-searing palettes, and textile mismatches.

Not to sound too hopelessly nitpicky, but a lot of Mulan's most vibrant outfits don't fall right. Court wear lacks the crispness of structured silk, the long sleeves draping more like pseudo-Renaissance than Imperial fashion. Then there's the matter of the colors, which often look so bright as to be gaudy. One respects the willingness to go against the elegant watercolor aesthetic of the animated original, but the results don't satisfy. It's all fun to look at, and it would be a lie to suggest Daigeler's designs don't inspire wonderment. However, an accumulation of minor issues amounts to a mountainous objection, the sort which makes an Academy Award nomination a bit hard to swallow.

4) MANK, Trish Summerville

Have you ever wondered who styled such iconic early-00s music videos as "Lady Marmelade" and Christina Aguilera's "Dirrty"? That was Trish Summerville, a costume designer who started in fashion and quickly became a sensation in the music world, creating wild costumes for performances, styling fantastic looks for the cameras. Throughout, Summerville also did some work in magazine editorials and film, assisting costume designer Michael Kaplan in such projects as David Fincher's The Game. It was that connection that ended up guaranteeing Summerville's instant success as a full-time movie costume designer.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was her first feature as a credited costume designer, and more extravagant projects followed, such as The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Summerville pulled garments directly from the runway in all these productions, using her connections to the fashion world as an integral part of her craft. In that regard, Mank represents a subtle change of pace for the designer. Instead of imagining the future or dressing a contemporary drama, Summerville was challenged to invoke the glamour of 1930s Hollywood for David Fincher's jagged nightmare about Citizen Kane's much-celebrated screenwriter. We're strictly in the realm of history while also dealing with a movie designed to be presented in silvery monochrome instead of vivid color.

Edith Head once used blue-tinted sunglasses to surmise how a specific color would register in black-and-white. Summerville, blessed with the advantages of modern technology, used her phone to check textiles' appearance in monochrome. The result of such efforts is a ghostly vision of a gone-by era, metallic greys and cold silvers dominating the frame. Patterns are sparingly deployed, textured materials even more so, inspiring an image characterized by its absolute control. One can feel the restraints around which the characters live, the gold chains that trap them, the poisonous nature of their glamor. Even Marion Davies' lamé evening gown transpires vile portents, her figure looking like an oil spill specter haunting the gardens of Hearst Castle.

Pulling from vintage pieces and building many more from scratch, Summerville constructed a wardrobe that tells the story of passing time, delineating the end of an era of Hollywood history. One can see, for instance, how Oldman's suits gradually evolve from the style of the early 1930s to the 40s. Nonetheless, Summerville also scaled down some of the era's more absurd quirks. Feminine hats are simplified or erased altogether, ill-fitting outfits of real life are adjusted for a cleaner look on-screen. Nevertheless, the designer still found space for some fun. In the Circus-themed party, for example, we see Mayer dressed as a lion tamer, a fabulous visual lark about the man's position as head of MGM, wrangler of ferocious stars.

3) PINOCCHIO, Massimo Cantini Parrini

When a pupil becomes a master, that's when a pedagogue can be genuinely proud of their work. While legendary Piero Tosi isn't with us anymore, I'd like to imagine he was proud of Massimo Cantini Parrini, a student of his who has become, in the past two decades, one of Italy's best working costume designers. Apprenticing at the legendary house Tirelli Costumi before becoming an assistant to Oscar-winning designer Gabriella Pescucci, Parrini represents the perpetuation of a long tradition of artistic excellence in Italian cinema, theatre, TV, and opera. Furthermore, he's a passionate collector of antique clothing, studying closely their details, accumulating knowledge about the techniques that span from the 1630s to our modern day.

Such gifts have reflected positively in his craft and, while Pinocchio marks his first Academy Award nomination, he's been worthy of gold for some years now. His previous collaboration with director Mateo Garrone, Tale of Tales, is even more splendorous than this Collodi adaptation. In any case, we're here to explore the wonders of this new twisted fairytale about a wooden boy whose nose grows when he lies. Garrone didn't run away from the text's nightmarish imagery in his telling of the old story, embracing the grotesque with as much passion as he celebrates the story's poetic qualities.

Parrini's costumes follow this same logic, negotiating varying levels of enchantment and horror. Without sticking to any definite period, the designer evokes the 19th-century while keeping the story necessarily separate from actual history. This is a tale happening out of time, a dream rather than a look back at the past. Nonetheless, the period detail helps ground the fantasy, especially when it comes to Parrini's use of ornamental elements, his treatment of textiles, the way he ages outfits to convey the idea of a decaying world. This Pinocchio universe is like a corpse, rotten until the flesh blooms with bright colors, rusty blood and bubbling bile, a garden of flayed flesh, flowers made of dancing maggots.

While every single costume is worth analysis and much praise, I'd like to shine a light on the figure of the Blue Fairy. Made up to look like an Angel of Death, skin, and hair powdered into an azure pallor, she appears both as a child and an adult. Both times, Parrini dresses the odd character in early Victorian dresses, just as pale as her skin, accessorized with delicate veils. She looks both like a bride and like a ghost, a shot of dying light flashing in the dark cosmos of this fairy tale. It's a breathtaking sight, so rich in detail it looks palpable, so ethereal it's also out of reach. Like smoke, we can feel the fairy's faint presence with our outstretched hand, but we cannot hold her.

2) MA RAINEY'S BLACK BOTTOM, Ann Roth

I've previously sung Ann Roth's praise and written about her extraordinary work in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, but that was before the costume designer got her fifth Oscar nomination, thus becoming the oldest nominee of all-time. Technically, it's a three-way tie, 89-year-old Roth sharing the record with James Ivory (Call Me By Your Name) and Agnès Varda (Faces Places). It couldn't have happened to a more deserving individual, a veritable titan of film and theatre history whose work spans six decades and over a hundred features. As things are looking, she might even get her second statuette, having already won in 1996 for The English Patient's wartime elegance.

While there's much to look at in the main character's costumes, this is a minimal wardrobe compared to its competition. At most, we have three costume changes for six actors, and that's probably an overestimation. If not for a dramatically needless prologue, Roth's work would be limited to Ma Rainey and her band's clothes during the recording session that structures the narrative. Still, even with little opportunity to explore each part, their personal style, how they fit into their time and place, the designer manages to pull off an astonishing feat of character building through costume.

The most obvious example is the titular Ma Rainey, played by Viola Davis, whose body was padded to achieve the Blues Singer's appropriate silhouette. We see her performing on stage first, decked in berry tones and royal blue, every inch of her covered in gorgeous ornament. There's the famous gold coin necklace worn by the real Ma Rainey, the theatrical use of ostrich feathers, the beautiful pleating and draping of early 1920s fashion. Instead of going for Jazz era clichés, Roth dressed her cast in distinctive styles, reflecting the variety of the time and how each character projects an image of themselves.

Just compare the heavy fabric luxury of Ma with the lightweight flow of Dussie Mae's dresses. One woman weaponizes her wealth, the other her sensuality, but both have to play the same social game within a profoundly bigoted society. As for other actors' outfits, the men's costumes don't call as much attention to themselves, but they're no less exquisite. We get to see how each member of the band contrasts with his colleagues, from Cutler's suave perfect tailoring to Toledo's old-fashioned lines. Chadwick Boseman's Levee is the only one whose costumes are heavily featured by the camera, his yellow shoes becoming an ominous symbol of golden aspirations that are bound to be smeared with dirt, blood, death, and disappointment.

1) EMMA., Alexandra Byrne

I'm not the biggest Alexandra Byrne fan, but even I can't deny the majesty of what she accomplished in Autumn de Wilde's Emma. The designer has long created a filmography full of maximalist spectacles of excess, full of stylized takes on historical and superhero fashion. Sometimes her designs work surprisingly well and manage to be one of the few bright spots in an otherwise mediocre affair like The Phantom of the Opera. On other occasions, Byrne's taste for undisciplined modernization can get in the way. Mary Queen of Scots, with its nonsensical saddlebags, denim court wear, and elf-like armor, is probably her nadir, but that didn't stop AMPAS from nominating Byrne.

Considering the precedent, I went to this new Jane Austen adaptation with a fair bit of caution, expecting to have to appreciate the film despite Byrne's ostentatious mess. Surprise of surprises, the designer has delivered one of the most fascinating Regency wardrobes in a long time, maybe the best dressed Jane Austen adaptation ever filmed, and a monument of accurate historical stylings that put hundreds of other period dramas to shame. By not modernizing the past, Byrne explores the oddest and most idiosyncratic aspects of early 19th-century fashion to conjure a strange vision that feels anachronistic but isn't. Not at all.

The costumes of Emma. aren't extraordinary just because they're faithful to historical truth. Part of Byrne's genius lives in the way she used the extremes of Regency proportions to create visual humor, making comedy out of clothing. The titular character's penchant for unpractical millenary and blindingly bright outerwear make for some hilariously incongruent sights. There's also a sharpness to the designs, a pointed quality that inspires awe, simultaneously entertaining and alienating the spectator. It's impossible to imagine this cutting version of Austen's social satire with different costumes, so integral are they to the flick's tonal balance.

As far as individual costumes go, there are no words capable of describing the tailored perfection of Anya Taylor-Joy's pelisses or the coordinated yellows of hers and Johnny Flynn's outfits. Mia Goth parades a glorious array of costumes that act as faded reflections of the protagonist's wardrobe, the shadow of financial inequity cast over their friendship at all times. Bill Nighty is a perfect model for the Regency menswear trends rendered in pale shades, making him one with his house. At the same time, Miranda Hart's fussy accouterments reveal her character's insecurities long before her smiles falter. Then there are Josh O'Connor's over-starched collars and his on-screen wife's fashion victim confections. It's all both sensual and funny, as beguiling as it is ridiculous, a triumph of costume design that's unparalleled within this Oscar race.

Predictions: I'm going to predict Roth tentatively, but I wouldn't be surprised if either Summerville or Byrne got it instead. Emma. has the advantage of the flashiest costumes, while Mank gets a noticeable boost as a Best Picture nominee. In truth, any winner but Mulan would be a victory worth rejoicing.

What about you, dear reader?

Are you enchanted by Disney magic, seduced by Old Hollywood Glamour, fascinated by the grotesqueries of Italian fantasy, dazzled by Jazz Age fashion, or are the splendorous oddities of the Regency period too good to resist? Which achievement in costume design gets your vote? Sound off in the comments and vote on the Oscar chart.

OTHER CATEGORY REVIEWS

- Adapted Screenplay

- Cinematography

- Costume Design

- Makeup and Hair

- Original Song

- Sound

- Visual Effects

- Documentary Feature

- Shorts, Animated

- Shorts, Doc

- Shorts, Live Action

plus

- Um... who is winning best actress?

- Double acting nomination complications

- How often does Best Actor go to a non-Best Picture nominated film?

- New Oscar records

- History of Posthumous Oscars

- Oldest Best Actor Nominees of all time (two are from this year!)