The Honoraries: Liv Ullmann in "Persona"

Wednesday, March 16, 2022 at 10:30AM

Wednesday, March 16, 2022 at 10:30AM We're celebrating each of the upcoming Honorary Oscar winners with a few pieces on their careers.

Sometimes, a film is so great that it robs you of words, leaves you speechless, struck dumb with awe. It's been a bit over two years since I've started writing for The Film Experience and, in that time, it's been a privilege to write about some of the best works of cinema I've ever seen. Ingmar Bergman's Persona tops them all and, when facing its wonder, it's hard to articulate anything. Perhaps no other film has been as tirelessly examined in the history of criticism, making it impossible to bring anything new to the discussion. And yet, it remains mysterious, as beguilingly unknowable as when it premiered in 1966. To try and write about it is a maddening exercise.

Even so, a celebration of Liv Ullmann wouldn't be complete without mentioning the first work in the artistic collaboration that forged her legend, that's at the center of her legacy…

When dealing with such a complicated object as Persona, maybe one should start by describing what happens on-screen. A prologue sets the stage for a strange hallucination of cinema, where a boy wakes up on a morgue's slab and interacts with projected images, like the diffuse visages of two women. After that dreamlike introduction, the narrative starts proper, focusing on Elisabet Vogler, a stage actress who, one night, suffered a breakdown. What first manifested as a barely controlled urge to start laughing during a serious scene has devolved into near catatonia. She either can't or won't speak, reduced to a state of functioning awareness and little to no communication.

Nobody seems to have an explanation for the sickness, and neither Bergman nor Ullmann will ever offer an answer that unlocks the mystery. Seeing no physical blocks or indices of mental ailment, Elisabet's doctor sends her out to the country with Alma, a young nurse assigned with the actress' care. Ensconced to a cottage, lost in the middle of nowhere, the women forge a peculiar dynamic. Alma talks non-stop as if to fill the gaping void of silence. She talks of her life, her history, sharing intimate details that feel too personal to vocalize. Elisabet watches on, embodying that same silence, that same voracious void. She listens and listens, studying Alma with detached amusement, a hint of condescension.

Around the film's midpoint, Elisabet writes a letter to her husband. Finding the unsealed envelope, the nurse pours over the typed words, discovering how much she's been regarded as an object of study, a curiously weak personality worth examining. After the revelation, Alma grows bitter, full of fire and fury. Loud arguments escalate to threats of violence. The silence once filled with meandering monologues is now slashed through with accusations, cutting jabs, spouted agonies. In no time, the text gets confusing, with Alma expressing words that feel like they belong to Elisabet. When that distant husband comes for a short visit, not only does he treat Alma as his actress wife, but he seems unable to acknowledge the presence of two separate entities.

And that's when Persona arrives at its most famous scene. Percolating in guilt and self-loathing, Alma imagines a life story for Elisabet and proceeds to tell it to the other woman. In essence, we witness how a weak personality reacts to the gravitational power of a much stronger one, attacking the pulling force through an act of projection. The nurse imagines the actress's biography to reflect her own anguishes. It's a distorted mirror of all the stories of sexual dalliances and regretted abortions she once shared with the woman she considered a friend, maybe a sister. And so, the weaker identity shatters, reconfiguring its fragments around the stronger one, finding, at last, a way to resolve its quandaries. Alma sees the worst of herself in Elisabet.

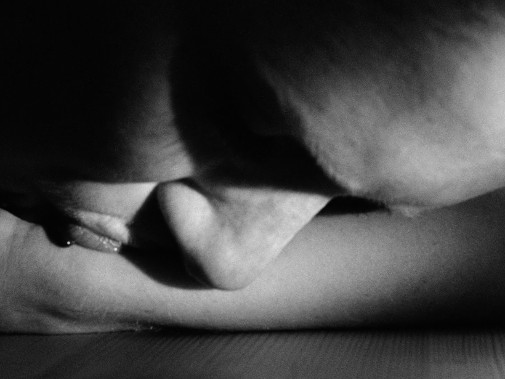

The scene happens twice, once with the camera looking at Elisabet, then with Alma in the center of the frame. A last haunting image serves as punctuation, the women's faces merged through an optical effect, an uncanny chimera. In the aftermath of the exorcism, the vampiric Elisabeth seems to fade as Alma dominates. Power relations inverted, the nurse abandons the cottage. We never quite know what happens to Elisabet. The last we see of her is in the hospital, a memory of mirrored smiles floating through the celluloid haze above her exhausted face. Through it all, cameras have played a major role, as have sudden bursts of meta-cinematic disruptions – burnt reels, blurry lens, and even a flash of the cameraman operating his machinery.

In essence, it's a straightforward film, an insular chamber piece composed almost exclusively of monologues to which Ullmann's Elisabet listens. The voice of Bibi Andersson dominates the aural dimension, but it's the close-up pas-de-deux of films faces that delineates the visual idioms. Yet, despite such simplicity, the ideas it evokes are nearly as complex as they are infinite. Reading through the work of countless critics and academics, one is bound to find a myriad of explanations for what Persona is about. Identity is a possible answer, though sexual repression also has its champions. Morality, the divinity of the creative act are other possibilities.

Maybe, to me, the one that rings truer is an idea that Persona, above all else, is about cinema. It might be THE film about cinema in the medium's history. In any case, we're not here to celebrate Ingmar Bergman's directorial brilliance, his script, Sven Nykvist's crystalline black-and-white cinematography, or even Bibi Andersson's tour-de-force as Alma. This is a Liv Ullmann celebration, after all. The truth is Persona may not feature the most accomplished screen performance by the Norwegian thespian. It's certainly not her most outwardly complex. Even so, I count her Elisabet Vogler amongst the essential screen creations in my life as a cinephile. Considering her, I once learned to recognize what most inspired me about the seventh art. I learned how to appreciate its riddles.

The mere sight of her face in this first collaboration with Bergman takes my breath away. There's a shot of her lying in bed, unblinking eyes focused somewhere to the audience's right. The music swells on the radio, and the light dims, two bright spots reflected on her vitreous gaze. I don't know what to tell you, I don't know why, but while revisiting this moment for the write-up, I suddenly started to tear up. It's as if Ullmann's Vogler isn't just drawing Alma's soul, her identity, out of the woman. She's doing her vampiric magic on me too. Oh yes, Elisabet is a bit of a soul-sucking ghoul. A vampire and a ghost, the character's a fleshy mound of neediness and an unsolvable enigma.

Though, that may be a misclassification of Elisabet's role within Persona. It's such a minimalist performance, so structurally limited, that it's difficult even to say if Ullmann is playing a character or an abstract collection of concepts. Bibi Andersson's Alma is a person. Liv Ullmann is a black hole instead. Or maybe she's cinema in the shape of a woman. The text makes it clear how she finds the nurse entertaining, watching her with a look that's full of want. It's the desire to know something, to capture it perfectly. Smiling at Alma, Elisabet's smiles feel loose and human, if only for a moment. However, her eyes betray the hunger, the curiosity. They're that black hole sucking everything in – cameras. They frighten me.

And yet, it'd be unfair to say Ullmann portrays Elisabet as an unfeeling monster or detached beyond reason. On the contrary, the woman feels horror, taken to the extremes of anguish when observing a Tibetan monk's self-immolation on TV. The use of actual footage of death makes the moment unforgettable and vile, like a shot of existential alarm that comes from the screen straight into our hearts. Ullmann isn't cinema in that single instance. She's a reflection of the audience, a copy taken to the limits of poised expressivity. It has been said that everything one can say about Persona can be contradicted and still be valid. The reverse too. That sounds like a contradiction in terms, but it describes both the film and Ullmann's strange work in it.

That idea came from film historian Peter Cowie, but the best summation of Ullmann's Elisabet Vogler already exists in Persona's screenplay. Before sending her off to live with Alma in the remote countryside, the doctor says:

Don't you think I understand? The hopeless dream of being. Not seeming, but being. Conscious and awake at every moment. At the same time, the chasm between what you are to others and to yourself. The feeling of vertigo and the constant desire to at last be exposed — to be seen through, cut down, perhaps even annihilated. Every tone of voice is a lie, every gesture a falsehood, every smile a grimace. Commit suicide? No, too nasty. One doesn't do things like that. But you can be immobile. You can fall silent. Then, at least, you don't lie. You can close yourself in, shut yourself off. Then you don't have to play roles, show any faces, or make false gestures. You think…but you see, reality is bloody-minded. Your hideout isn't watertight. Life seeps in everything. You're forced to react. No one asks if it's real or unreal, if you're true or false. It's only in the theater the question carries weight — hardly even, there. I understand you, Elisabet. I understand your keeping silent, your immobility. That you've placed this lack of will into a fantastic system... I understand and I admire you. I think you should maintain this role until it's played out, until it's no longer interesting. Then you can drop it, just as you gradually drop all your roles.

It takes one hell of an actress to take that description and build a screen creature out of it. Indeed, no other performer ever understood the cinema of Ingmar Bergman as masterfully as Liv Ullmann did. She somehow manages to articulate the paradoxes of Persona, from the most negligible micro expression to the wildest action. Even her laugh is a contradiction. Softly sounding, it rings like a cruel bell, a vicious sound of judgment. How can something be delicate and devastating simultaneously, gentle and violent? It shouldn't work, but it does. While Bibi Andersson delivers the showiest performance throughout the movie, Ullmann holds the key to Persona's mysterious mechanisms.

She is the wonder at its center, the miracle of its mystery, the crucial ingredient of Ingmar Bergman's most enduring masterpieces. She is Liv Ullmann, and she's one of a kind. There will never be another like her.

Persona is streaming on the Criterion Channel. You can also rent it on Apple iTunes.

Honorary Oscars,

Honorary Oscars,  Ingmar Bergman,

Ingmar Bergman,  Liv Ullmann,

Liv Ullmann,  Persona

Persona

Reader Comments (5)

I know I'll never "understand" it all. I don't even think Ingmar Bergman "understood" it all. I think it's the greatest film ever made.

Great article!

One of my favorite films, Bergman created so many masterpieces, but this one is really special, Andersson and Ullmann are two sides of the same coin, and of course Nykvist cinematography is just perfect.

One of the most beautifully oppressive films I have ever seen,a haunting final shot and 2 top calibre actresses.

Since ABC was so eager to ‘drop’ those 8 categories to be ‘edited in later,’ with more shaved time now available, it sure would be great to have these Honorary Oscar recipients speak. Would love to see a Ullman montage/speech, but I guess ABC wants more ‘comedy routines and jokes’ for the coveted audience who has no time for Liv Ullman’s legacy…

Persona is cinema at its most sublime: haptic, gestural, a map of ever-shifting human emotions.