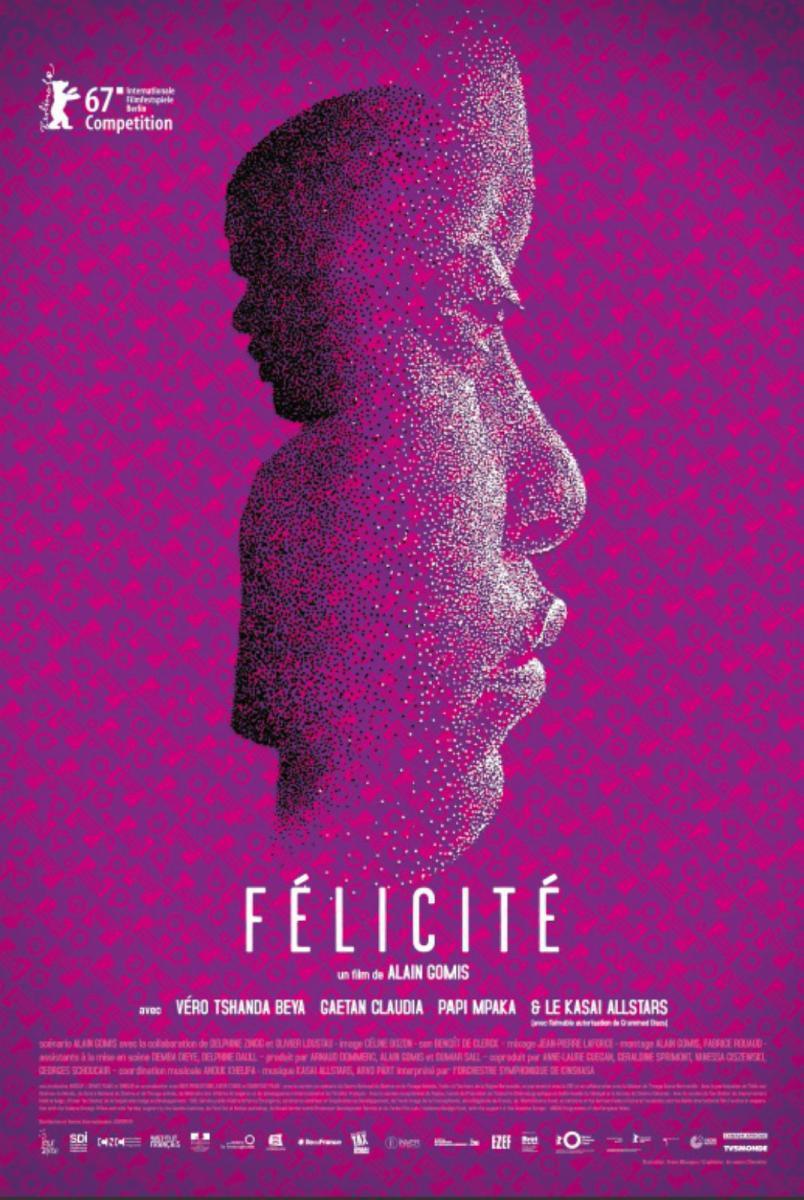

Interview: Alain Gomis on Why Senegal's Oscar Submission 'Félicité' is a Film About the Modern World

Wednesday, November 1, 2017 at 8:00PM

Wednesday, November 1, 2017 at 8:00PM By Jose Solís

The title heroine of Félicité is unlike any film character you’ve met. As played by Véro Tshanda Beya Mputu, she’s both larger than life and an everywoman trying to make a living as a singer in a Kinshasan bar. When her son Samo (Gaetan Claudia) has a devastating motorcycle accident, Félicité is forced to go in a race against time, as she tries to find the money to pay for his treatment. But this is only the first of Félicité’s many plights and before we know it, the film has become a soulful character study in which a woman must learn to accept love from others. If the film sounds like a social drama, it’s only because director Alain Gomis uses that familiar structure to invite us into a world that will seem new to many, but once inside he defies the conventions of genre and traditional plot to convey something more lyrical.

The film has been selected as Senegal’s official Oscar entry and is now playing in select US theaters. I spoke to Gomis during the New York Film Festival, where the film was shown, and learned about his process, and why he thinks his film is a reflection of the modern world. Read the interview after the jump...

JOSE: You’ve spoken about how you let ideas simmer for a couple years before turning them into films. Was this the case for Félicité?

ALAIN GOMIS: Yes, I don’t start to write immediately but I look at paintings, photos, I take notes and then try to let the film come.

JOSE: What insights do you gain during that time? Can you give me an example of something you learned about Félicité that you didn’t learn while doing Andalucia for instance?

JOSE: What insights do you gain during that time? Can you give me an example of something you learned about Félicité that you didn’t learn while doing Andalucia for instance?

ALAIN GOMIS: The process was very similar for both, I would perhaps say this time I felt more confident. I tried not to panic when I didn’t have answers. Sometimes you have pieces that enlighten other things, so you work here and there and suddenly realize you can write because you have what you need. In this film we deal with her ego, she’s a warrior, I love her this way, but she can’t even accept love for example because she doesn’t have time for that. She’s busy trying to stay alive and making the minimum she needs to survive. She doesn’t compromise. In a way you can’t force your work, it’s a way to destroy yourself. If you want to continue to live you need to accept some things and find a balance between what you can fight for and what you must accept. When I understood that I was more able to articulate the fear.

Since you approached this project with more confidence, did some of the answers come during the shoot then?

Yes, some came at the end of the editing. We continued changing things, it would be awful to have a film down on paper and not allow yourself to discover things when you meet the actors for example. You need to allow yourself to go deeper, in the end I’m always surprised with what I end with.

Your heroine is an artist, even though it’s a cliché many people assume artists create characters just like them, so if this were the case in your film do you find that putting your fears, hopes and dreams in your character help you deal with them in your own life?

I think you have to find a personal relationship with every character, you have to find a place where it’s you also. You have dialogues with them.

Music is such an important part of who Félicité is, she channels her love through the music. Why was making her an artist important?

It allows me to have a character who can remain silent but you can hear her voice. The voice of a singer is also her internal voice, you can be more elliptic in a way, you don’t need to explain things because you have the voice. In this film I had the voice before finding the actor. Originally I had imagined this skinny woman and ended up with Véro who is perfect. Sometimes you’re looking for green and then find a blue only to realize it’s what you were looking for.

The film made me think of two opposites: silent films since we have Véro’s beautifully expressive face doing more than words, but also it’s kind of like a musical too. How did you find the balance for that?

You know of the Kuleshov effect, which was the same shot of a man but each edit meant something different, so this is really this important relationship, it’s the shock of two frames that in your mind create an emotion. So we have this silent movie element which obliges the viewer to put yourself in the character, that way your relationship with the film is stronger. The film becomes an experience rather than something you watch. The musical element allowed me to have choreography that helped find a harmony with the silent moments. The film has a melody and a musical relationship, I can’t say it in a more precise way because for me it’s not a concept. It’s not theoretical, I have this overwhelming me, and have to find a way to do tai-chi of sorts with these elements.

You based the medical dilemma Félicité’s son faces on a cousin of yours. Was there a conflict with your family in wanting to show this personal story?

No because I don’t see a frontier between my life and my films, the only thing is I wanted to be honest. I wanted to bring personal things into the film and also have real people, we shot in a real hospital where we had 3 or 4 people die every day during our shoot. We could hear the families crying, so when you do things like that you ask yourself questions about what we’re doing here. I’m not here to steal something from the life of my family member, in fact when he watched the film he came to me with no words, he just gave me a long hug. At this moment this film is all my life, all that I got is in the film. There are no barriers, everything of me is in there.

Credit: Jose Solís

Credit: Jose Solís

How do you recover from that?

In fact I’ve learned the more you do the more open you become. The more naked you are the more you receive. Sometimes you think you have to be strong, but if you accept your weakness you end up receiving more.

Congratulations on the award in Berlin. After watching the film in New York I read other reviews and people kept comparing Félicité to other iconic female characters from Neorrealism, someone like Anna Magnani or Sophia Loren, or Ozu heroines. I know we need references to understand the world, but I actually had never seen a heroine like Félicité onscreen before. As a filmmaker of Senegalese heritage are you ever thinking about creating new references, new parameters of characters so one day we won’t hear people comparing characters like this to Magnani but rather in a few years hearing “oh, this is such a Félicité kind of character”?

It’s true about doing film in Africa and for non-European, Western filmmakers, that you try to create a new archetype because we need it. We need new references. Even if dialogue with other references is important, you need to recognize yourself in the Anna Magnani character, but doing this film I tried to create a new modern mythology to say that we are the modern world. Twenty years ago if you wanted to make a film about the modern world maybe you went to New York, but if you want to see what is the real world today come to Kinshasa. You will see the real world without the makeup, it’s the same as yours and you can learn from it too. We have European archetypes which are important but creating our own archetypes should be the mission of painters, writers, filmmakers, with the hopes that in the future maybe not Félicité but some other African character will be the reference for some Polish guy. We need that! In our cities and countries you see why it’s important to see ourselves and not have this feeling that you don’t exist, or to have the feeling that to exist or have the right to exist we have to look like someone else. This hurts us, it’s violence against us, because we are told not to love ourselves. It’s really, really, important for me to have these strong characters that you don’t have to like or dislike, but can have dialogue with. You see characters like Tarzan who are in Africa killing people who look like you, watching TV in Africa you don’t see people who look like you, this is not possible! It’s too complex for a kid to grow up not being in dialogue with himself.

I grew up in one of the poorest countries in Latin America and you grow up with the dissonance of being told you should aspire to be the Bruce Willis character in the action movie, but your skin isn’t the same color, so you know you can never be him. You’re either the criminal, the maid, the gardener, the drug dealer…

You can have something like a “black Bruce Willis” but you can also say the maid character is somebody, she’s not just an example. She’s more important than Bruce Willis because she represents 90% of the world population. What Hollywood tries to sell to us doesn’t exist, trying to create a society where everybody wants to escape their own condition is a nightmare!

You’re based in France and even there we’re seeing the rise of the extreme right. Something hard for a person of color is seeing that white people are finally waking up, but they don’t realize they have a 100 year long advantage over us in the arts. We have always known that, but they don’t. You’re Senegalese and French, do you ever wonder if white European people deserve more patience or do they just need to hurry up and learn?

I’ve had the chance to live between France and Senegal. In Senegal nobody’s white, you’re human. There are a few white people, but to learn to be a minority is important. I feel more and more confident because everybody’s realizing we are the biggest part of the world. For me realizing it makes you wonder how it was possible we accepted being oppressed when it came to seeing our own image. Now it’s OK, we don’t have to fight anymore, we just have to say “I’m here!” if you don’t want to look at me you don’t have to, but we’re here. We are the people.

Félicité is now in select theaters.

Alain Gomis,

Alain Gomis,  Oscars (17),

Oscars (17),  Senegal,

Senegal,  foreign films

foreign films

Reader Comments (1)

The director is a really attractive man.