The Furniture: The Cluttered, Musty Madness of King George

Monday, June 5, 2017 at 2:00PM

Monday, June 5, 2017 at 2:00PM

"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Play adaptations are frequently criticized for not being “cinematic” enough. It’s as perennial a complaint as it is a silly one. Many of the best play adaptations don’t abandon their more theatrical elements, they use cinema’s unique capabilities as an especially potent additive.

Play adaptations are frequently criticized for not being “cinematic” enough. It’s as perennial a complaint as it is a silly one. Many of the best play adaptations don’t abandon their more theatrical elements, they use cinema’s unique capabilities as an especially potent additive.

The Madness of King George is a great example, a film that juxtaposes the visual freedom of on-location shooting with the precision of period sets. Adapted by Alan Bennett from his own play and directed by Nicholas Hytner, it chronicles the Regency Crisis of 1788. King George III (Nigel Hawthorne), perhaps as a result of porphyria, lost his grip on reality. The Prince of Wales (Rupert Everett) petitioned Parliament to have his father removed from power, and to have himself declared regent. It very nearly worked.

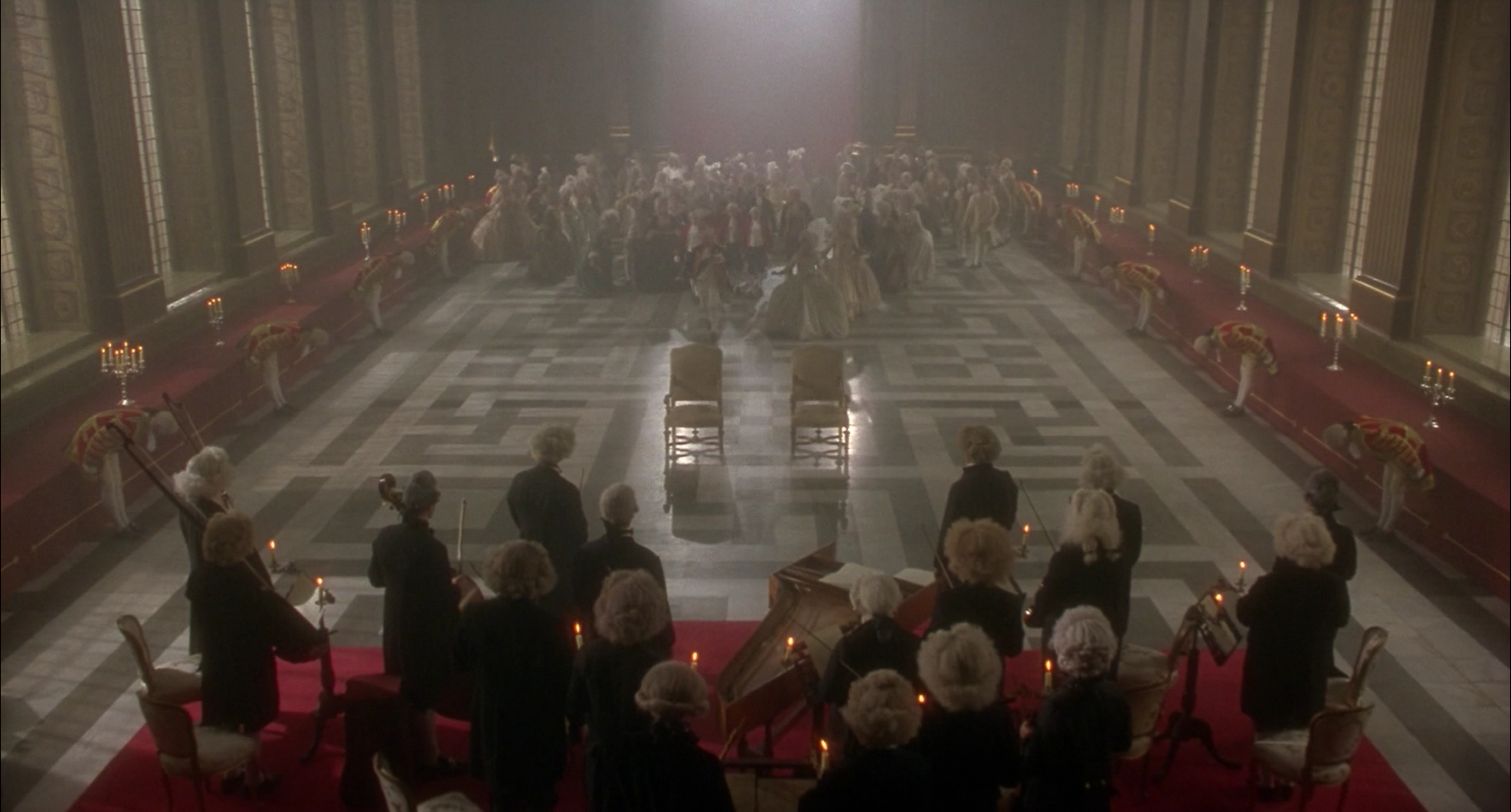

Bennett eschews much of the legal complexity, instead focusing on the King’s mercurial psychology. As he moves from palace to palace and doctor to doctor, the only thing that remains steadfast is Queen Charlotte (Helen Mirren). Everything else is at odds, a theme underlined by the Oscar-winning design. Production designer Ken Adam, art directors Martin Childs and John Fenner and set decorator Carolyn Scott modulate between the peace of open sky and the stuffy absurdities of 18th century royal living.

An early symbol of this is Arundel Castle, which stands in for Windsor Castle. Originally built in the 11th century, it has seen many destructions and renovations. Hytner pans from its oldest tower to its 18th century additions in one shot. This proud building represents quite a history of noble life, from windswept Norman simplicity to Georgian opulence.

The King lives and works in its cramped rooms, overstuffed with expensive furniture and populated by an army of servants. His office has a simple desk, but it is surrounded by books no one reads and chairs where no one is allowed to sit.

This life, while ornate, is hardly pleasant. No one is ever comfortable, or even particularly clean. The utter lack of both privacy and efficiency follows the King even into his bedchambers, where his three servants bunk together in a closet.

Parliament, ostensibly the more democratic and enlightened institution, is as chaotic. Those who can’t fit into the room itself pile into its open windows, where even the Prince of Wales is just another body squirming to get a better look at the action.

The tragedy is that King George truly loves the countryside, the farmers and farmlands of England. It’s no wonder he grows desperate, surrounded by such cacophony. He rushes out to the fields at the crack of dawn, when the sky is a beautiful clear blue and there’s no one around to bother him with stupid questions.

Bizarrely, though Bennett uses actual humorist medicine as the butt of some excellent jokes, the visual logic suggests that George’s madness is all about the elements. The King lacks fresh air and the balance it provides. He needs a physician with relevant experience, one whose pioneering mental hospital is a fully functioning farm.

When Dr. Willis (Ian Holm) arrives with bits of his agricultural asylum in tow. He and his assistants restrain the King almost immediately, before they even have the time to clean up the hay that fell out of the crates. The castle has become a barn.

The constant whirr of political intrigue must be kept away. The Prince of Wales, meanwhile, seems poised for victory from the very beginning. It is a long, hard road for King George.

However, one scene stands out as a brief glimpse at tranquility. The King and Queen find themselves on the castle roof. Adam and the design team have embellished it, adding six more chimneys. The atmosphere is theatrical, a Stonehenge in the sky. It is here, an oasis in the storm, that it is first clear that even a King needs a little air to breathe.

Reader Comments (7)

It always amused me that Ken Adam, whose name is synonymous with modernism, concrete and steel, won his two Oscars recreating period environments. (That he only received one nomination for his work on the Bond films is a crime).

Hawthorne was robbed.

I love what you tweeted about this movie.

I haven't seen this one since it came out, but I remember loving it - a rewatch is in order.

The "it's not cinematic!" arguments frustrates me so much. Like, what was Denzel Washington meant to do with Fences (to take the most recent example I could think of)? And why should people care if the writing and the acting is still so good?

markgordonuk - Robbed! By Forrest Gump no less! Such nonsense.

Peggy Sue - Thanks!

Glenn - People are desperate to isolate film, as if relationships with other arts are somehow cheating, or less rigorous and dignified. I think it's a weird holdover from when people didn't take film seriously as an art, but also that was decades ago and people should really move on.

Hi, my name is muskaan and i am staying in Goa. for more about me visit my website: