The Furniture: The Magnificent Amberson Mansion

Monday, July 10, 2017 at 10:30AM

Monday, July 10, 2017 at 10:30AM

"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Much has been written about the making of The Magnificent Ambersons, the conflict between Orson Welles and RKO, Robert Wise’s studio-mandated shorter version, Bernard Herrmann’s refusal of credit, and the loss of much of the original footage. It’s a fascinating story.

Much has been written about the making of The Magnificent Ambersons, the conflict between Orson Welles and RKO, Robert Wise’s studio-mandated shorter version, Bernard Herrmann’s refusal of credit, and the loss of much of the original footage. It’s a fascinating story.

However, this column isn’t about that. There remains plenty to celebrate in the version that was released to theaters, 75 years ago today. At the top of that list is the Amberson mansion, a triumph of design that should stand next to Citizen Kane’s Xanadu. It’s like a Victorian ancestor to the great palace of Charles Foster Kane, a previous iteration of wealth’s excesses. But the story of The Magnificent Ambersons is not about a meteoric rise in fortune, but what comes after.

Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Booth Tarkington, the film begins in a fictionalized late-19th century version of Indianapolis. The Amberson family is at the top of their city’s financial and social life. Here is their manse in its prime.

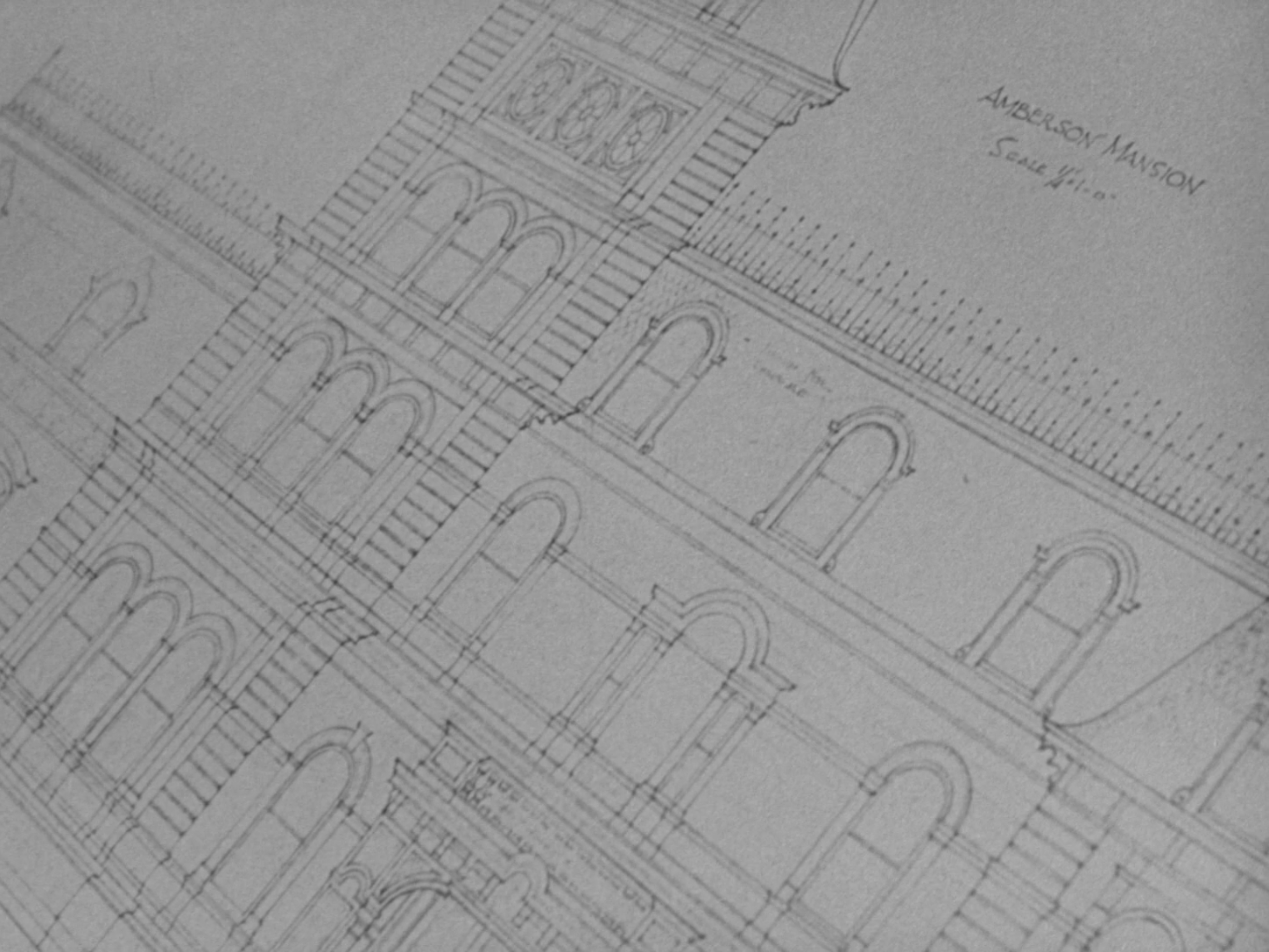

Welles shows gratitude to the design team in the famous credits sequence. Set designer Mark-Lee Kirk’s name is read over this image of the mansion blueprint.

The work of set decorator Al Fields, meanwhile, is represented by this quite impressive chair.

Together, along with the rest of the design team, they created a Victorian palace. Its front garden features Classical sculpture, for class, and an enormous bronze deer that suggests the triumphalism of Manifest Destiny.

The Amberson daughter, Isabel (Dolores Costello), is being wooed by a young inventor named Eugene (Joseph Cotten). But it doesn’t work out, and she marries a boring Hoosier named Wilbur. They have an awful child named George, who terrorizes the town with his manners, his carriage and his curls.

Then the film jumps forward twenty years. Eugene, now a widower, attends an enormous party at the Amberson house with his daughter, Lucy (Anne Baxter). This is the first real tour of the interior, and it does not disappoint. Here is the anteroom, where Major Amberson and his family greet the arriving guests.

There isn’t a ballroom, exactly, but a series of interconnected rooms for dancing and mingling. They seem to go on forever, another gilded salon beyond every ornate door frame.

But the grand size of the house is not ideal for family living. That evening, the grown-up George (Tim Holt) picks a fight with his mother and his aunt Fanny (Agnes Moorehead) about Eugene. The house seems to swallow up not only this petty drama, but also the people participating in it. George, Fanny, Isabel and Uncle Jack (Ray Collins) bicker between doors and shout around corners, communication hindered by architecture.

They all seem so small. And as they slowly destroy each other’s futures in an endless series of selfish gestures, they only seem smaller. The house, meanwhile, seems to extend further and further upward. Fanny and George turn the stairwell into a locus of conspiracy and frustration, each desperate to prevent Isabel and Eugene’s happiness.

This vertical, oppressive atmosphere is in great contrast to the source of Eugene’s new money. His automobiles are lower to the ground than horse-drawn carriages, and more kinetic. They drive the borders of Indianapolis outward and lower real estate values in the center of town, including the mansion. As the century turns, the Amberson name loses its wealth and influence to this upstart, forward-moving world.

George is left behind. His commitment to the staircases and the ideas of the past have led him to disaster, a penniless solitude in a house that he soon must abandon. His comeuppance comes in a room full of shadows and sheets, an alcove in the cavernous architecture of a dead age.

Reader Comments (5)

Worth mentioning that the big Amberson mansion staircase set was re-used in a bunch of RKO films. For example, in the beginning of The Seventh Victim, it appear as a private school for girls.

Very informative look at an almost great movie with brilliant production design and the way it influences the audience's perception of the characters actions and the characters themselves. As impressive as the design is it's the towering performance from Agnes Moorehead that was my main takeaway from the film.

I can never decide which is the greater achievement - this or Kane.

In either case, both are among the greatest American works of art in any medium - novelistic in depth and psychological insight but unquestionably cinematic in their execution.

Far out I love this movie. I'd love the chance to see it on a big screen to soak up all of that exquisite design (and Moorehead's powerhouse performance).

The exterior of the Amberson mansion appears to have been partly inspired by the exterior of Thurlow Lodge in Menlo Park, California. This massive Second Empire country house was torn down in the early 1940s with much of its contents being auctioned off. The Hollywood studios bought a lot of it for set decorations.