De Laurentiis pt 2: The '60s epics of Dinocittà

Tuesday, August 6, 2019 at 6:30PM

Tuesday, August 6, 2019 at 6:30PM This week at TFE we're celebrating the centennial of one of cinema’s most prolific and legendary producers, Dino De Laurentiis. Here's Tim Brayton...

Yesterday, Eric took us on a tour of the first phase of Dino De Laurentiis's one-of-a-kind career as a producer, the era when he and Carlo Ponti helped usher a number of major works of late Neorealism into the world, introducing the first wave of international art cinema masterpieces. We now arrive at the 1960s, when De Laurenteiis was emboldened by those early successes to indulge himself in the first of his many flights of staggering, ill-advised ambition. Near the start of the decade, De Laurentiis opened a movie studio on the outskirts of Rome, an enormous playground for moviemaking nicknamed Dinocittà (after the famous Cinecittà, then and now the heart of the Italian film industry).

The Dinocittà experiment perfectly describes De Laurentiis's singular personality. A visionary producer can tell what is going to be popular in the future, and thus can jump in on trends at the moment of their inception. The hacks who make up the bulk of commercial producers know what was popular a year ago, and thus crank out movies that feel like uninspired cash-grabs and knock-offs. De Laurentiis had the gift and curse of knowing what's popular right this instant, and so his biggest swings – and too often, his biggest misses – came out just barely on the back side of the historical moment when they could live up to his extravagant hopes...

In the case of Dinocittà, that historical moment was the titanic success of 1959's Ben-Hur, an American film that entered production at Cinecittà late in 1957. That film reignited the public's love of huge-scale ancient world epics, and promised a robust future of huge-budget Hollywood projects filming in Italy.

It was, in other words, a superb time to already own a big studio that could accommodate these massive-scale productions, and a reckless time to create one from scratch. For, of course the ancient world epic fad was just that: a fad.

The demise of Dinocittà made global headlines

The demise of Dinocittà made global headlines

The public's taste for multi-hour extravaganzas with mid-size armies of extras and sets that occupied the space of small towns petered out in the middle of the decade, leaving De Laurentiis with a huge financial liability that couldn't pay for itself. Dinocittà continued along into the early 1970s, producing several much-beloved films along the way, including the 1967 Italian omnibus The Witches, Franco Zeffirelli's 1967 adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and the beloved 1968 campy cult favorites Barbarella and Danger: Diabolik. It even hosted a few American productions looking for room to stage an outdoor epic, notably the 1972 adaptation of the stage musical Man of La Mancha. But with the Italian industry switching to much smaller scale outdoor productions for much cheaper genre films, such as the spaghetti Westerns, sustaining Dinocittà became an impossible dream.

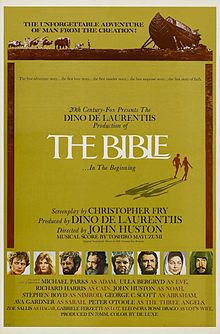

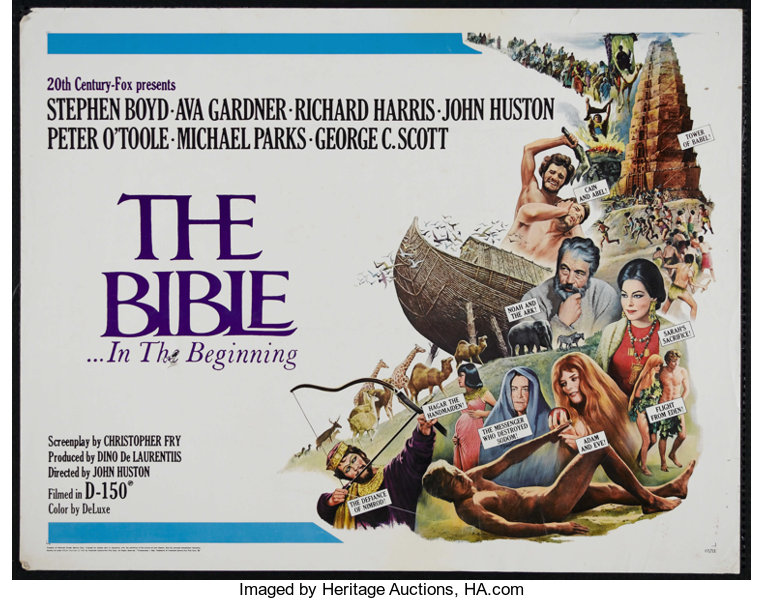

If Dinocittà itself typifies De Laurentiis's grandiosity in its fullest extent, it's perhaps his production of The Bible: In the Beginning, released in 1966, that best encapsulates his '60s misadventures in one single movie. As the title suggests, this was meant to be the first in a monumental series of films adapting the whole of the Bible, an idea that would have been astonishingly hubristic at any point in film history, though less so in the '60s than before or since.

The Bible is typically regarded as the dying gasp of the Bible epic. It was a hit, but at great cost: it shares with fellow shot-in-Italy superproduction Cleopatra the ignoble status of being the highest-grossing film of its release year while still failing to turn a profit, on account of its unimaginable budget (although The Bible cost a mere fraction of that infamous boondoggle).

But this does mean that De Laurentiis was willing to spend an incredible amount of money (much of it belonging to 20th Century Fox) to make The Bible the biggest, most incredible spectacle that could be managed. You can levy any criticisms against the film you like, but there's no disputing that it's dumbfounding in its scale. Nor is it a safe movie. Even as he was busy latching onto commercial fads, De Laurentiis still clung to the faith in artistry that we saw in his 1940s films.. Here, he handed the film's reins to director John Huston, hardly a devoted Christian, and stood back while Huston turned the film into an unfathomable combination of visual effects showcase, cornball adventure movie, and full-on art film. The Bible earned one Oscar nomination, for its score by Toshiro Mayuzumi, a Japanese avant-garde composer; and it sounds like a score by an avant-gardist. For every clichéd motif for strings and horns, there's a thorny, atonal passage like the jarringly modern drones that accompany Huston's abstract representation of the creation of the world as cinema itself literally coming into focus. The opening reel of The Bible is the most defiantly uncommercial filmmaking to be found in the whole of the Bible epic genre, full of austere imagery of empty primitive landscapes that anticipate the opening sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey by two full years, while Huston warmly and authoritatively intones passages from the King James Version as the film's narrator (he also plays Noah and, immodestly, God Himself).

Adam & Eve and Noah get the epic treatment

Adam & Eve and Noah get the epic treatment

Covering the first half of Genesis (through the "Binding of Isaac" story), the film is a disconnected series of anecdotes, with each major story (Creation, Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham) shot in a different way. Even by the standards of these bloated Bible films, it doesn't cohere, nor seem like it wants to: the impression one gets is that Huston was having a grand time playing with big-budget spectacle, and wasn't bothering himself with storytelling much at all. This works until it doesn't: the Noah sequence is a warped comedy of Huston merrily interacting with animals, then the intermission comes, and the film spends the rest of its time on stultifying, overlong story of Abraham and his wife Sarah (George C. Scott and Ava Gardner), leaning into the dullest failings of the genre.

For all that, though, the money is visible onscreen. That's what makes it a De Laurentiis film, more than anything: it goes awry in its desire to provide audience-friendly spectacle, but it's never cautious or conversative or cheap. It goes all in on creating a living world in unexpectedly bold, artistic ways, and it's money well spent, even if it's obvious that the producer was never going to see that money come back. That peculiar combination of savvy mercenary instincts and a terrific willingness to overspend is what ultimately killed off Dinocittà, though what a magnificent death!

Continue to Part 3: Mark Brinkerhoff follow De Laurentiis to the United States, where he reinvents himself.

or return to

Part 1: The critically acclaimed Italian breakthroughs

Reader Comments (2)

I can't believe i"ve never seen this one when biblical epics were pretty common in my house growing up. Great write-up, Tim!

"Cinecittà, then and now the heart of the Italian film industry"

Is it still the center of the Italian film industry? When I went there, in the summer of 2012, it was mostly empty with only some tv productions still using the installations. Looking at MDB there seem to be some films still shot there, but not many.

Most of the Gangs of New York sets were there still, their space never needed to shoot something else, rotting away. They even warned us not to approach the Five Point set since parts of it were falling apart and it was too dangerous to go near.

I even signed a petition to keep it active since they were talking about selling the lot to build a residential area. The workers were protesting outside the gates the day I went there.

Meanwhile, Dinocittà has been turned into an amusement park.