Women's Pictures - Jennifer Kent's The Babadook

Thursday, October 29, 2015 at 8:15AM

Thursday, October 29, 2015 at 8:15AM Happy early Halloween, everyone!

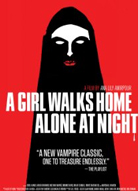

In the comments section of last week's post on A Girl Walked Home Alone At Night, a brief but lively discussion sprung up over whether folks prefer the Iranian-American vampire flick, or Jennifer Kent's inaugural feature film, The Babadook. Rather than pit the two films against each other, let's just take a moment to appreciate the fact that in 2014, we got two really good, buzzed-about horror films from two new female directors. This, as much as any other reason, is why I hope 2014 will be remembered in the future as one of those Great Years of Film.

In the comments section of last week's post on A Girl Walked Home Alone At Night, a brief but lively discussion sprung up over whether folks prefer the Iranian-American vampire flick, or Jennifer Kent's inaugural feature film, The Babadook. Rather than pit the two films against each other, let's just take a moment to appreciate the fact that in 2014, we got two really good, buzzed-about horror films from two new female directors. This, as much as any other reason, is why I hope 2014 will be remembered in the future as one of those Great Years of Film.

Anyway, it could be argued that whether you prefer A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night or The Babadook is partially determined by whether you prefer indie swagger to conventional horror. But to call the film "conventional" would be to sell The Babadook incredibly short. At first glance, The Babadook looks like a stylish example of a supernatural thriller, but the genre tropes hide a dangerous film about the subconscious strife between parent and child. [More...]

Essie Davis,

Essie Davis,  Horror,

Horror,  Jennifer Kent,

Jennifer Kent,  The Babadook

The Babadook