A Year with Kate: Mrs. Delafield Wants to Marry (1986)

Wednesday, November 19, 2014 at 5:00PM

Wednesday, November 19, 2014 at 5:00PM Episode 47 of 52: In which Katharine Hepburn stars in a geriatric version of The Way We Were.

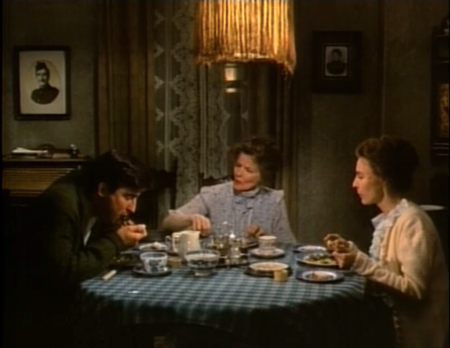

Mrs. Delafield wants to die. The TV movie opens on an ambulance rushing the society widow to the hospital after an unnamed relapse. Obscured by a breathing apparatus and various medical paraphernalia, Mrs. Delafield lies comatose as her children begin to mourn and divvy up her estate. Her neighbor waxes elegiac on the imminent elegancy of her death. Then, a handsome doctor puts a hand on her shoulder and--miracle of miracles! Mrs. Delafield opens her eyes! And then, out of nowhere, it becomes a marriage comedy.

Mrs. Delafield wants to die. The TV movie opens on an ambulance rushing the society widow to the hospital after an unnamed relapse. Obscured by a breathing apparatus and various medical paraphernalia, Mrs. Delafield lies comatose as her children begin to mourn and divvy up her estate. Her neighbor waxes elegiac on the imminent elegancy of her death. Then, a handsome doctor puts a hand on her shoulder and--miracle of miracles! Mrs. Delafield opens her eyes! And then, out of nowhere, it becomes a marriage comedy.

After last week’s morbid misfire of a movie, the opening of Mrs. Delafield Wants to Marry feels a little like purposeful trolling. Grace Quigley extolled the virtues of death for the elderly with an ailing Hepburn at its center, but Mrs. Delafield Wants to Marry celebrates the life they still have yet to live. Our Own Kate as Mrs. Delafield makes her actual entrance 15 minutes after the morbid opening, and what a difference two years makes! Kate is bubbling and happy and in full health. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t breathe a tiny sigh of relief. She’s okay! Sure, she can’t carry wood anymore, like she did in On Golden Pond, but that doesn’t matter. She’s too busy carrying the movie.

Mrs. Delafield Wants to Marry is about life, or rather the difficulty of having a life when your children start to treat you like a child. Mrs. Delafield falls in love with Dr. Silas (Harold Gould), the doctor whose touch revived her in the prologue. Unfortunately, Dr. Silas is Jewish, and Mrs. Delafield is the kind of rich, blue-blooded WASP whose name ends up on symphony programs and university lecture halls. Her kids, in a shocking bit of anti-semitism for 1986, don’t want her marrying a Jew. His kids don’t want a goy stepmother. Both are called irresponsible when all they are is in love. What are a pair of star-crossed septuagenarians to do?