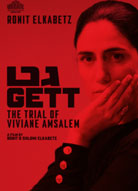

Interview: Ronit and Shlomi Elkabetz on 'Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem'

Monday, February 16, 2015 at 10:39AM

Monday, February 16, 2015 at 10:39AM  Jose here. In Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem, Israeli goddess Ronit Elkabetz returns to play a part she’s lived with for more than a decade. In 2004, Ronit and her brother Shlomi teamed up as writers and co-directors of a film trilogy that would concentrate on the experiences of a woman as seen through the roles society imposed on her. In the first installment, To Take a Wife, Viviane must deal with being trapped in a loveless marriage to her husband Elisha (Simon Abkarian), in 7 Days, Viviane must sit Shiva and come to terms with the fact that she is obligated to mourn despite not feeling pain. In Gett, which opened this weekend on the heels of its Golden Globe Foreign Film nomination (Oscar passed it by), Viviane is trying to gain her freedom from Elisha, but finds that practically impossible given that her husband hasn’t committed any “sins” against her; her request is deemed invalid by the strict rabbinical court.

Jose here. In Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem, Israeli goddess Ronit Elkabetz returns to play a part she’s lived with for more than a decade. In 2004, Ronit and her brother Shlomi teamed up as writers and co-directors of a film trilogy that would concentrate on the experiences of a woman as seen through the roles society imposed on her. In the first installment, To Take a Wife, Viviane must deal with being trapped in a loveless marriage to her husband Elisha (Simon Abkarian), in 7 Days, Viviane must sit Shiva and come to terms with the fact that she is obligated to mourn despite not feeling pain. In Gett, which opened this weekend on the heels of its Golden Globe Foreign Film nomination (Oscar passed it by), Viviane is trying to gain her freedom from Elisha, but finds that practically impossible given that her husband hasn’t committed any “sins” against her; her request is deemed invalid by the strict rabbinical court.

In the years since her breakthrough in Late Marriage (2001), also an Israeli Oscar submission, and the first Viviane installment, Ronit has become the face of Israeli cinema having delivered brilliant performances in films like The Band’s Visit and Or. Gett also reveals her growth behind the camera with a much more sophisticated directorial technique, as she and Shlomi tell the story from a very subjective point of view. With their use of the camera and precise shots, they allow Viviane to have the freedom of thought society continues to deny her. A perfectly cast ensemble makes the film a worthy spiritual companion to A Separation and Zodiac, in a way, as they all explore the frustration that comes along with endless, inefficient bureaucratic processes.

During their recent visit to New York City, I talked to Ronit and Shlomi about their collaborations, their unique use of cinematic language and how Gett has rightfully become a sociopolitical sensation in Israel.

The interview is after the jump...

Viviane (Ronit Elkabetz) and Carmel (Menashe Noy) in GETT. Courtesy of Music Box Films

JOSE: You’ve been making movies together for quite a few years now. Growing up were you the kind of kids who would put on shows at home?

RONIT: Actually we were not like that at all.

SHLOMI: We were the kind of children who would each stay in their room and didn’t talk much (laughs) each of us was in our own world. We were very dreamy kids.

RONIT: I’m the oldest, I have three younger brothers, and the energy at home was quite something. Our trilogy of films is inspired by our parents. I took my time to observe everything, Shlomi is eight years older than me, so by the time he arrived I was almost a lady already.

SHLOMI: We were less about putting on a show and more about analyzing what went on around us. It was a very special household, because there were things in it that contrasted, we had our mom’s side which was very secular, and our father who was very religious. We were brought up in a way that we were allowed to be whatever we wanted to be, so we would always wonder if it was because our parents were very liberal, or because they simply had no time to deal with us (laughs). One of the wisest things our parents did was to encourage us to do what we wanted to do, we were never repressed.

RONIT: Our father really wanted my brothers in the synagogue…

SHLOMI: ...and expected Ronit to be married by age 23.

RONIT: ...and I got married at 45 (laughs)

SHLOMI: I guess we drew a new story based on our parents’ expectations and the kind of people we wanted to be. We didn’t come from an artistic family though, our father worked in the post office, our mother is a hairdresser, but we come from a very spiritual background, with a lot of respect for the world.

You established from the beginning that you wanted to make three films about Viviane. Why did it have to be three films specifically?

RONIT: Because there was so much material! We had so many insights! We had a lot of material that we talked and dreamt about, so much that we wanted to understand. We lived with this story.

What I mean is, why three films as opposed to a television series for instance?

RONIT AND SHLOMI: (in unison) Oh noooooo! (They both start laughing)

SHLOMI: Everybody wants to make TV today. (Ronit keeps shaking her head) It was never the thing though, we never wanted to extend this story forever. We were not telling this story, there were so many insights that had to do with Israeli culture and the situation of women, it had to do with the Mizrahi Jews. We didn’t want to put this in a TV show, we needed something that would stand up for much longer in a solid way. We also always wanted to make cinema, to watch this story in the big screen. It’s different to watch this in a social context, with 400 people, rather than having a TV show. Our films are very political and cinema was the right platform.

Ronit & Shlomi on the set of Gett. Courtesy of Music Box Pictures

Ronit & Shlomi on the set of Gett. Courtesy of Music Box Pictures

The film could have easily been a public service announcement, but you never patronize your audience or recur to over-explaining. How did you find the right tone in the writing process?

RONIT: Our audiences are intelligent! (Laughs) I’m kidding, but it’s very easy to fall into clichés when you feel you’re writing something “social”. This is why our cinema is revolutionary in Israel, both in style and form, and also in its content. This is the first time where you see the Sephardic Jews talk about themselves in a movie, in a very authentic way. We are talking about ourselves, so we aren’t trying to get people to like us, we’re just speaking from the truth of our souls about ourselves, so that’s what makes this universal. It’s really important to understand that in Israel, in our short cinematographic history, till our film, Sephardic people weren’t telling their stories. The Ashkenazic were telling all the Sephardic stories, and what do they know about us? They know about as much as I know about you! It would be like having a white director tell the story of a Puerto Rican immigrant in America.

SHLOMI: We didn’t need to explain anything, we just showed. For example, what is more intimate than to show a close up of an African American person on the big screen? You don’t need to explain anything. We understood that from the beginning, we understood that a shot in itself could be very political, images can be very political. We don’t need to create a manifest, the image is us, the image is the manifest.

You’re also making the audience become active viewers. Nowadays people tweet and text throughout the movie and if they come see your film and do that, they will get lost.

RONIT: (Laughs and nods)

SHLOMI: We want them to be active in more than one way. With Gett we actually have people talk to the screen, in the moments when the man is being asked if he’ll grant Viviane a divorce, in every screening I’ve attended, I’ve heard people scream “yes!”. They become very engaged with the story, but also the film itself became a political event, it became a movement, it moves people to act upon the subject they see in the story. It shows the influence of cinema in society, in a few weeks, the organization in charge of Rabbinical courts will show the film, can you imagine that? These judges for the first time will see their court represented from the point of view of a woman. We never dreamed of anything like this, no one has ever gotten judges to talk about changing the law before.

Have people suggested you become politicians?

SHLOMI: We are in politics!

RONIT: But politics are so boring, why would we want to do that? We’re doing our part through our art and I believe this is the best way. Naively I believe that cinema has power, so if you put all your heart in what you’re doing, and want to tell the world something, the proof is right there for you to see. The movie has become so popular that we ended up having a lot of meetings with politicians.

SHLOMI: Of course they all want to use the movie to their best interest. They want to connect to it and use it to their advantage, the good thing is that it’s not only the left, people from the extreme right, everyone wants a piece of this.

RONIT: Every day I have to talk to a politician.

SHLOMI: Especially with the upcoming elections in Israel. We are very wanted.

Ronit, you also preside over Ahoti - For Women in Israel, which seeks to empower women in your country. Will all the outreach you do, have you seen a rise in women directors behind the camera?

RONIT:Yes, definitely.

SHLOMI: When we started directing you could count female directors on one hand.

RONIT: We were like three or four women at first. There were more women doing documentaries, but none were doing fiction features, but now, ten years after, wow! There are so many women doing films, which is wonderful.

Viviane (Ronit Elkabetz), Carmel (Menashe Noy) and Shimon (Sasson Gabay) in GETT. Courtesy of Music Box Films

Viviane (Ronit Elkabetz), Carmel (Menashe Noy) and Shimon (Sasson Gabay) in GETT. Courtesy of Music Box Films

JOSE: Your preparation for Or is rumored to have been brutal. And you immersed yourself similarly into your character in Late Marriage. Since this is your third time playing Viviane, do you find it easier to slip into this character?

RONIT: Doing the first Viviane film was very difficult for me, also because I represent something very intimate, and second because I also directed it. So I had to run from back and forth from the camera to see what I was doing. The second film was easier, and the third, look, after ten years in Viviane’s shoes considering the cinematic language we chose for this one, it was much easier to breathe inside the character. She’s in my blood now, she’s in my veins. I need to prepare a lot, I work pathologically on the character’s soul. It’s important for me to do this, so when I come to the set I can make choices as Viviane.

SHLOMI: This film in particular, we had to create the role of Viviane and the weight rests on her shoulders, but she doesn’t speak. This is her story but she has no words. So how do you create a character that doesn’t speak? She sits for two hours. One of our thoughts when we did this film was that we knew Viviane was invisible, and what we see in the court is what she sees. This is her life she’s fighting for in this court, but she doesn’t get to talk about it. We didn’t want to use any master shots in this film, we didn’t want to describe this court, we only wanted to place the camera where the characters were. You don’t see something unless the character sees it, if you see something you get to see the reaction of the person talking to them. We stretched this room to capture the reactions of all the characters. One of the most interesting things we discovered during the shoot is that there is nothing but this one silhouette of Viviane, and she tells the story just by looking. Viviane is like a sculpture, we didn’t want to impose any drama on her, but just from shooting what she saw, we created her story.

I like that you said you were “in Viviane’s shoes” because I believe she speaks a lot through her clothes and her look. By the way she wears her hair and her sparkly sandals, you can tell this is a woman who doesn’t conform to the rules of her society. Was all of this in the screenplay or did you allow the actors to bring pieces of themselves to their parts?

RONIT: We didn’t let them change any comma in the screenplay (laughs) because we know what we want. At the same time we were very open.

SHLOMI: We work in very strict boundaries! We usually call at a certain hour, but we don’t start working until we have chosen the right look for each character, the right shoes, the right shirt. That’s probably why producers don’t like us (laughs). The minute we decide how the scene will look, we move pretty fast.

RONIT: We don’t like improvisation. We like to be free in our text, and for that the actor must be very prepared. Freedom comes after the work. I expect from my actors what I go through myself. Only like that can we do what we want, in the theater for example, it’s only after a few months of playing the same part, that we can start doing things we didn’t think about before, because we forgot the text and the work, and we can live in the moment.

Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem is currently playing in select theaters

Reader Comments (3)

oh wow, that is A LOT of crap coming from Ronit and Shlomi.

" This is why our cinema is revolutionary in Israel, both in style and form, and also in its content. This is the first time where you see the Sephardic Jews talk about themselves in a movie, in a very authentic way. " - just,, false. seriously, Gett is NOT revolutionary, and we have had many Sephardic jews talk about themselves on films before Gett (maybe not before their previous films, but defintily before Gett).

I Really Disliked Gett outside of Menashe Noy's excellent performence. Also, i fail to see how the film is un-patronizing. Viviane SCREAMS the message of the film at the ending, in case the audience doesn't get it.

Help Please I just didn't get how it ended. Someone please explain. Thanks

Foxit Reader Crack Foxit Reader Crack rsload is a small, fast, and feature-rich PDF reader that allows you to open, view, and print any PDF file.