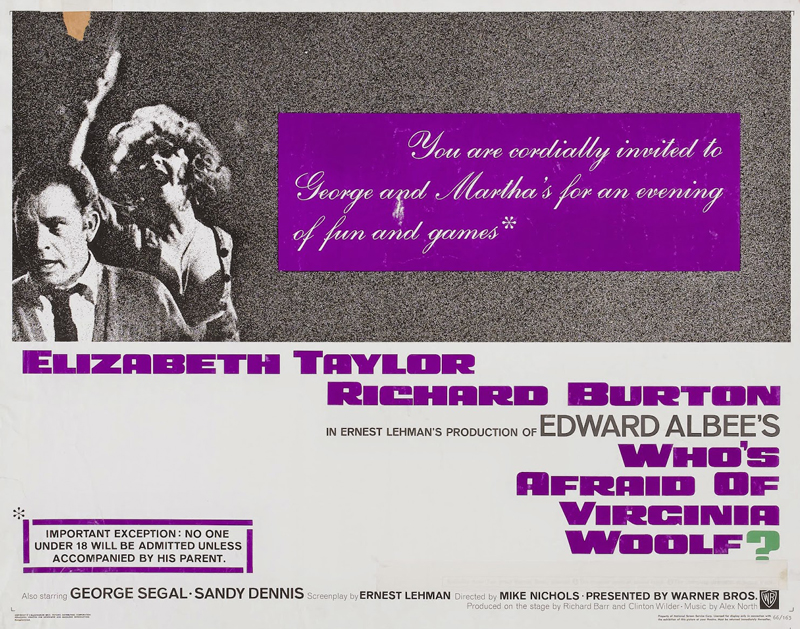

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Pt. 3: "Get the Guests"

Thursday, June 23, 2016 at 3:15PM

Thursday, June 23, 2016 at 3:15PM For the 50th Anniversary of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) Team Experience is celebrating with a four part miniseries. Begin with Part 1 "What. A.Dump!" or Part 2 "Firing Squads & Flop Sweat" if you missed them.

Pt 3 by Kyle Stevens

[Kyle's book "Mike Nichols: Sex, Language, and The Reinvention of Psychological Realism" is available for purchase.]

01:04:30 We pick up with Nick and George, left alone. Nick ceases peacocking for a moment since the ladies have gone, and, for George, this is the moment to assert dominance. For Albee, their tête-à-tête is an allegorical showdown between biology and history, nature and nurture: what they are, what people are, and who gets to say. Albee is on George’s side:

To take the trouble to construct a civilization, to build a society based on principles of, uh, principle. You make government and art and realize that they are, must be, both the same. You bring things to the saddest of all points, to the point where there is something to lose. Then all at once, through all the music, through all the sensible sounds of men building, attempting, comes the Dies Irae. And what is it? What does the trumpet sound? Up yours.”

Thank you. Thank you!

1:05:52 Honey and Martha return from “the euphemism,” where Honey has been throwing up. Honey, who always seems to be out-of-step with the group, assumes that Nick’s sarcastic applause is for her. Her readiness to see everything as a performance, though, is also spot-on, hinting that she’s perhaps the most insightful one of the bunch...

Dennis crafts a willful ditziness that’s funny and captivating. She’s mesmeric.

Nick announces that he and Honey are leaving. Martha isn’t at all pleased, of course, as she’s not yet gotten enough of Nick’s goods, much less of George’s goat. But this is one of the central problems of the story, logistically speaking: how to keep Nick and Honey there. Why don’t they leave? It’s a question that niggled at Nichols as he planned the film and one of the reasons that he agreed to “open up” the play by moving the action of the next scene out of the house.

1:07:00 So, amidst George’s erratic driving—made all the more suspenseful by his prior anecdote about a boy killing his parents in a drunk driving accident—Martha starts poking around for a topic that will rekindle the foursome’s fire. She finds reason to start in on the bit about the kid again, recounting stories about how George used to make their son sick and implying that he scared the boy. George escalates matters, claiming that it was Martha who made their son ill because she was “breaking into his bedroom, kimono flying, fiddling at him, “always cornering him” and “coming at him.”

That they’re throwing around such dark accusations in order to embarrass each other is horrifying, especially if you don’t yet know how the story ends. If you do know, then you know that this is all improvisation. George doesn’t deny Martha’s premise (that the boy was molested). He plays by the rules of “Yes, and…,” which makes their fight both a fight and a game, even when she’s calling George a liar. Honey chimes in, sighing about her love of brandy. George says he used to drink brandy, and Martha, under her breath, mumbles “You used to drink bergin, too.” George swerves the car, making the huge mistake of exposing to Martha that she’s finally hit paydirt. She can’t believe that he’s told Nick about bergin.

That Martha knows this story alarms us. If we believed that George was telling the story about a boy he knew (and not himself), or that he was making up his story as he went along, we’re now confused. Martha assumes, wrongly, that George also told Nick about a book that her father blocked him from publishing. Throughout this car ride, Wexler’s cinematography is perfect. Heavy shadows and passing lights emphasize the interplay of secrets and lies, and close-ups maintain the sense of claustrophobia within the car, and the characters’ minds.

Oh I love dancing. I really do... I love dancing. I dance like the wind.

1:08:35 Honey, always intent on changing the subject, slurs that she wants to dance at a passing dive bar. Martha spies the opportunity to get close to Nick, informing Honey that she, too, loves dancing “with the right man.”

1:09:00 George slams on the brakes, and the movie crashes into the dive bar’s interior. Landing here is, in a way, returning to the story’s origins. Edward Albee said he got the name for the play from graffiti he saw scribbled on the walls of a college bar. This scene is the most visually trippy in the whole movie. It’s like a fever dream, heating the movie up from simmer to boil. The clutter all around the ramshackle bar is every bit as busy as George and Martha’s home. Our eyes still have no place to land. There is no stillness here, either.

There’s also no establishing shot; we’re just suddenly overhead, watching Honey twirl and twirl.

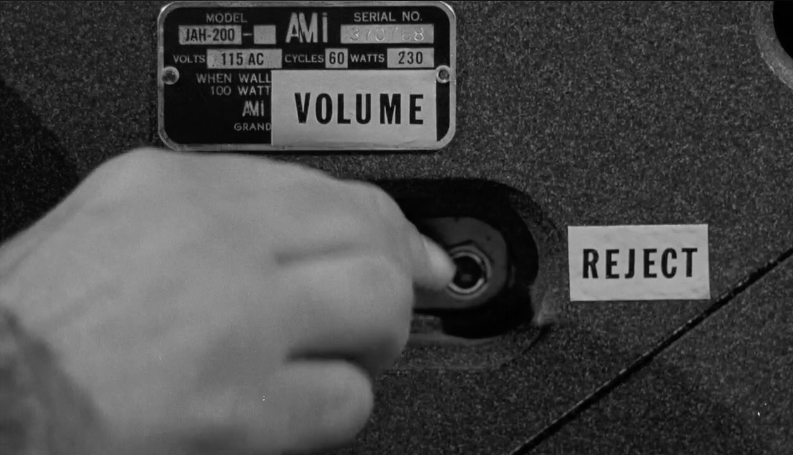

Martha orders George to play the jukebox, and he obliges with “The Anvil Chorus” from Verdi’s Il Trovatore (and if you wonder why the hell that’s available on a juke box in the 1960s, you’ve not spent enough time around fancy Northeastern colleges).

1:10:10 In a movie this baroque with irony, it makes a strange sort of sense that even though the characters have space to move, they feel even more trapped. Rather than respect the social etiquette of public spaces, they just yell louder. Tight two-shots and close-ups increase the tension. It’s all extremely uncomfortable.

George decides he’ll play Martha’s game and asks Honey to dance in the most nonchalant display of “game” ever:

Hi, sexy. Do you want to dance angel boobs?"

Martha puts on a rockin’ tune. Honey decides she’ll sit this one out, but Martha tells Nick he’s up. It’s worth bearing in mind that Nick is never named in the film, and this is one of my favorite ways he is hailed by Martha, simply as “stuff”:

Okay, stuff. Let's go.

Nick and Martha start out with a respectable early 60s dance, a few feet apart, though that it probably still too young for them. Martha only waits a few seconds before closing in. The pair pay no mind to their spouses and commence to grinding.

Having successfully shown that she can seduce Nick, Martha immediately makes her next move, bringing up George’s ill-fated book again. The angles of the frames become increasingly canted. Things are off kilter and about to topple over any second. As the pair discuss George to the beat of the music and thrust their bodies at each other in the air, they pay no mind to George’s running commentary.

You have ugly talents, Martha.

Martha spills the beans on George’s novel (whether they’re factual beans is anybody’s guess), and this, and her cavorting with Nick, is enough to rile George. He stands and demands she stop it. Suddenly, we’re treated to a wide shot.

01:12:53 George is about to take over the space that Martha has just danced around every inch of. Honey, always on it, hysterically screeches “violence, violence”—exposing that still waters really do run deep. Martha, knowing she’s really getting at George now, digs in deeper, telling Nick that the novel was “really” about George. That it was true, that it happened. And it is this that George can’t tolerate. He goes in to strangle Martha amidst Honey’s incessant cheers of “violence, violence!”

1:14:00 Nick helps break up the assault and George gathers himself. The owner intrudes to check on things and George tattles that they were “just playing a game.” Although his aim has been to leave, he now asks for one more round of drinks. George has a plan. He decides they should play another game, now that they’ve played “humiliate the host.” Burton is such a star. The man can command the screen.

George decides they’ll play “Get the Guests” and starts in on exposing Nick and Honey’s secrets. George sits the others down and now ascends to the stage himself.

Come on. We must know other games. College-type types like us. That can't be the limit of our vocabulary. There are other games...

01:16:30 He admits that Martha told them about his book, though he denies that there ever was such a thing, but “that’s blood under the bridge.” It was lines like this one that made me want to write about the film in high school (I did my senior thesis on it well before I ever knew I had any interest in Mike Nichols). There’s something so queer about all this parrying and thrusting of detection and disclosure, and, unlike a lot of classic camp, it’s so angry (not to mention smart and quick!). Part of what I write in my book about the history of this film was that in the 1960s Hollywood was learning that it was no longer enough for couples to learn to play the same games together (as in Bringing Up Baby). Couples needed an audience, others to acknowledge them, and that’s at the core of what (was then called) gay liberation was all about: couples seeing erotic and romantic acknowledgement..

George commences to inform the group that he wrote a second novel—clearly concocting it now—and exposing the secrets Nick earlier let slip.

Oh I love familiar stories. They're the best.

After George reveals Nick’s less than admirable reasons for wedding Honey, and her own mysterious disappearing pregnancy (or lie to secure his hand in marriage), Honey dissolves in tears and runs off to be sick again. Nichols’s camera continues to keep us on the edge, too. We don't know where we'll be next.

And that's how you play 'Get the Guests.'

1:20:32 Martha admits that that’s the most life George has shown in a long time, and he takes the compliment. The camera begins to follow them as they exit, but stops at the door, almost afraid of the showdown that’s coming.

And come it does.

Why baby, I did it all for you. I thought you'd like it, sweetheart. It's to your taste, blood, carnage, and all.

1:21:00 This parking lot scene is just electric. It’s so electric, in fact, that audiences couldn’t help but think they were seeing into the marriage of the world’s most celebrated couple. I doubt, though, that Liz and Dick were so metaphorically inclined during their in-house scuffles. This scene also feels climactic (until it doesn’t). At first, we think they’re finally saying the things that need to be said, airing their grievances, but little by little we sense that this isn’t the culmination of anything. Oh it’s a knockdown fight alright, but it’s also a demonstration that they’re no longer merely “walking what’s left of their wits,” as George melancholically puts it earlier in the evening. They are totally alive to each other now, totally on.

George stands up for himself, and Martha won’t have it. Martha paints a picture of George as submissive, wanting her to emotionally whip him year after year. He denies this, bone-tired of her delusions about him.

You can stand it. You married me for it.

1:21:55 The fight becomes so intense that the film can barely look at it. It becomes all blurry body parts and gray fury as Martha takes her turn at strangling. Indeed, throughout the scene, Wexler allows the characters to roam in and out of focus, visually echoing the heady mix of clarity and obscurity between the characters and their feelings for one another.

The tight frames and segmented faces call attention to off-screen space, to what can and can’t be seen, to the threats and fears always lurking just out of sight.

Martha backs away. We know they’ve fought before, but she’s in rare form tonight. George ain’t scared. Martha takes to frantic pacing as she formulates a plan, pacing like a cat, like a cat on a cold, gravel parking lot.

Martha: I'm gonna finish you beore I'm through with you

George: I warned you not to go too far

Martha: I'm just beginning.

George admonishes Martha for moving “bag and baggage into her own fantasy world.” And just when we think we might be getting some actual truth here, that George might be about to reveal what is fantasy and what isn’t in this crazy world, we realize that this is another gambit: he’s threatening to have her committed.

1:23:10 Liz is so good at showing the hurt that underlies vitriol. Martha moves to putting their whole marriage on the line, explaining that it has SNAPPED. In dialogue disturbingly close to things ordinary people say all the time, Martha laments the lies we tell ourselves in order to settle, to accept the disappointments of life.

But lest we think this is just another date night, she tells us tonight is different. Most sympathetically, Martha internalizes the failures of a relationship as her own, but nevertheless bristles at the idea that it’s all her fault. She knows it takes two to be this miserable. She reiterates that it (the marriage? their lives? their love?) is gone. SNAP. And here’s her brilliant move: she declares that she’s giving up. She’s done with him.

George agrees to play along:

George: There is no moment. No moment anymore when we could come together

Martha: Maybe you're right. You can't come togethere with nothing, and you're nothing. *SNAP* I looked at you tonight and you weren't there.

Martha delivers the ultimate blow: “you weren’t there.” As Nathaniel pointed out, from the first scene, there’s a question of whether, or in what way, they exist for each other. There’s a meditation on fiction woven throughout the movie, and also on America, a country that was invented to run on the promise of imagination, since they’re named after the first First Couple.

1:26:00 Martha keeps going, escalating matters. He asks, “Total war?” Her reply is unequivocal.

Total.

Their vehemence asserts their individuality even as it binds them. They’re testing the radii of their power over each other. Martha abandons George, picks up Nick and Honey, and speeds off to stage the final act.

Crucially, as George watches the car speed away, a little smirk passes across his face. He’s now writing a plan, too. War is a thing done together. They’re so furious, but clearly trying to convince each other that they don’t care. The irony is palpable. This scene is their declaration of love. They still care enough to fight, so there’s hope. It’s the sort of paradox that run throughout the play. It’s why it can feel so real and unreal at the same time. There’s a realism to the path their passions take. Jealousy leads to anger, and anger leads not just to vengeance, but—as in tales from The Iliad to King Lear—to mourning, as we’ll see in our final installment.

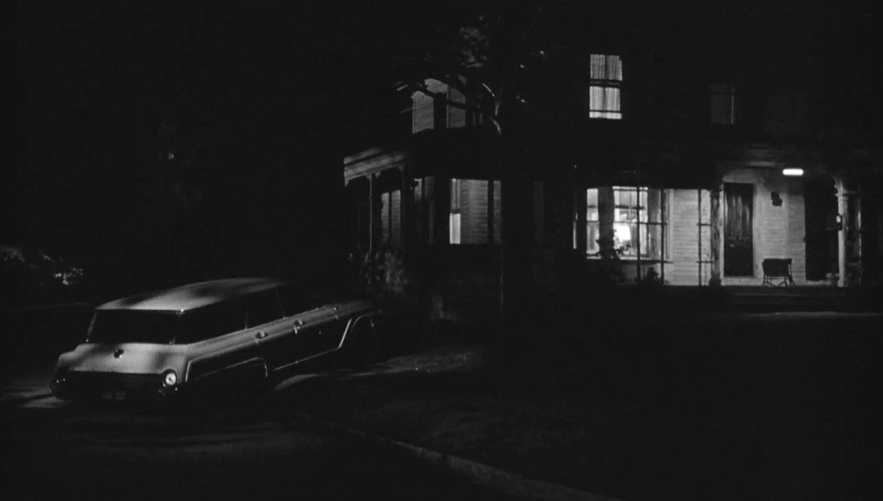

01:27:00 Meanwhile, back at the ranch, it appears Martha has managed to drunkenly park the car.

George finds Honey in its backseat, and the camera follows him, aligns us with him, as he wanders up to the house to find it locked. He breaks in and discovers that Martha and Nick are upstairs together, so he passes right on through. On the back porch, he cries, pathetically, a simpering mewl that turns into a full on sob the likes of which Sally Field would be proud. Burton has such range.

Honey stumbles to him, half asleep, and George realizes he can co-opt Honey (who has let slip a confession that she has had secret abortions). George concocts his final plan: to create a secret that Martha doesn’t know: that their son has been killed. Honey is starting to get it.

George rehearses delivering the blow. He’s ready to meet Martha on the final stage/battlefield.

1:33:55 Nichols then shows us the moon, as he did at the beginning of the movie, but now it’s the beginning of the end. A long pan across the sky is pierced by Martha’s braying of “Hey” and “George” as she stumbles into the night, wanting him like whiskey wants a glass.

Continue on to part 4, the finale, with Chris Feil.

Reader Comments (7)

i love it. especially the part about the context of gay liberation -- of relationships being seen/acknowledged/performed.

And i'm glad someone gay Richard Burton his due -- i know we were Liz obsessed early on but they really should have both won Oscars for this. It'd be the most perfect double Oscar win ever.

beautiful ending

nice.well penultimate ending. I'm excited to read Chris's finale tomorrow. I love doing these because as much as you can get your own fresh insight into classics on multiple views, other people's insights you might never come by unless you seek them out.

Well done Kyle for this analysis of the many layers which exist in this version of this film. When I re-watched it recently I found it almost too searing to take. Will there ever be another couple like Burton and Taylor who are willing to take this play on ? (on screen).

I can't imagine any major studio going with material this dark and difficult these days.

If they ever do a remake only cable TV or perhaps the BBC would be willing to greenlight a project like this.

Yet another reason to lament the decline of major film studios and Hollywood these days.

LadyEdith -- yeah. but plays also are rarely this good and provocative anymore. The closest we got recently was AUGUST OSAGE COUNTY which was amazing and hard and difficult and hilarious on stage and rather flat as a movie (sigh) due to several reasons but primarily lame filmmaking.

Oh and Kyle i forgot to mention -- and you didn't mention that beat where the waitress comes out with the last round of drinks and everyone shuts up. It's so FUNNy and uncomfortable as they wait for her to leave to begin their cruelty again (and she knows they're waiting for her to leave). Such a great random beat that always impresses me because the movie is so focused on these four characters that at that point int he narrative it's almost shocking that other people exist in the world.

kyle, truly enjoyed reading. great half-academic/half-fun take on this stretch of the film, and despite knowing the play and film well, i never made that excellent connection to Improv Rule #1 ("yes, and..."), which seems so obvious now that you say it. it's exciting in that context to think of how burton and taylor are playing it...it should seem very "actorly" but they are so far into the characters and their role-play that it feels "true". it's a great tribute to the high, high level they're acting on.

I'd been so excited to read your take Kyle and naturally you didn't disappoint!

On this rewatch I was struck by Martha's "you weren't there" argument because in her final son monologue she describes her own kind of mental retreat. Just because she's the one usually braying doesn't mean she hasn't faded in her own way.

Great write-up! The roadhouse set piece has always reminded me of a series of bombs going off.

Albee, though he has made nice regarding the film version of Virginia Woolf for official tributes, hated a number of things about the movie, the roadhouse scenes most of all. The dance scene could be considered over the top, but George's evisceration of Honey and Nick is brilliantly uncomfortable. And that showdown between George and Martha in the parking lot? Classic work, from everyone involved.

How does every actor in this film get their own tag on this post EXCEPT Liz? I'm shocked at the neglect shown toward Miss Taylor. ;)