Doc Corner: 'Nanette' Will Be a Defining Work of 2018

Tuesday, June 12, 2018 at 3:00PM

Tuesday, June 12, 2018 at 3:00PM  Rarely do stand-up comedy sets gain the sort of immediate notoriety that has greeted Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette. The comedian, writer and some-time actor who is probably best known to American audiences for Please Like Me (at least the few who actually watched it) has become a rare Australian exclusive for Netflix who are releasing Nanette alongside an ever-growing roster of stand-up comedy. It would be easy for this one to slide between the cracks of the streaming service’s much larger names. Who is Gadsby to non-Australian audiences anyway and why should they watch her? What about Nanette means it deserves to cut through the chaos especially when she comes across as so hostile towards the medium itself?

Rarely do stand-up comedy sets gain the sort of immediate notoriety that has greeted Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette. The comedian, writer and some-time actor who is probably best known to American audiences for Please Like Me (at least the few who actually watched it) has become a rare Australian exclusive for Netflix who are releasing Nanette alongside an ever-growing roster of stand-up comedy. It would be easy for this one to slide between the cracks of the streaming service’s much larger names. Who is Gadsby to non-Australian audiences anyway and why should they watch her? What about Nanette means it deserves to cut through the chaos especially when she comes across as so hostile towards the medium itself?

Well, for starters, to call Nanette a mere stand-up comedy special would be to do it a great disservice. As funny as it is, it isn’t the sort of work that neatly sits alongside Ali Wong, Chris Rock or John Mulaney. No, because Nanette is much more: it’s a manifesto, a doctrine, a philosophy. It’s a work of such searing potency that it deserves the attention of every man and woman with a Netflix account – and those who do not. It deserves to be hailed a landmark by LGBTQI audiencs, too. If you are wanting something to stake a claim to the most essential of-the-moment work of filmed entertainment for 2018, then Nanette is probably it.

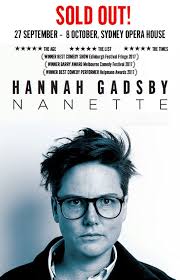

Big claim, I know, but Gadsby's show, winner of the Melbourne International Comedy Festival’s Barry Award and the Edinburgh Comedy Award, is a most radical thing indeed. Just 70 minutes long and bookended my minor glimpses into her life at home in Melbourne, Nanette is a work of such towering importance that it became legend the night it premiered. Perhaps best compared to Tig Notato’s famous set in which she revealed her cancer diagnosis, Nanette will likely leave audiences a bit battered and bruised, dewy-eyed and emotionally exhausted. Not exactly what you would expect when sitting down to a stand-up set on Netflix, I know. But it's also really funny.

It starts ordinarily enough, with jokes about her sexuality, lesbian humour, growing up in a small Tasmanian town, the opinions of comic critics and more through her delivery of odd emphases and vocal ticks. The show swerves somewhat soon after a story about how she narrowly avoided being gay-bashed because the man realized she was a woman. From here it goes somewhat more analytical. The laugh-out-loud humour dissipates (although still very much there) and instead we begin to see her attention at setup-punchline joke structure fray and veer into the inner-workings of a comedian’s mind. It’s smart and very sly, deconstructing jokes and infringing upon the contract made between comic and audience. It caught me off guard despite everything that I had read already. And while one may equate it to a magician revealing the truth behind the trick, it is an essential part of Nanette as it sets up the final act.

The camerawork in Nanette is pretty standard for a filmed stand-up set. One camera in front, another behind, one more to the side and one at the back of the Sydney Opera House where this show was filmed. This final one is important. Throughout the show, we occasionally cut to this shot showing the whole crowd laughing, applauding, thigh-slapping and cheering. But it’s at this part of the show where the crowd sits still and in silence. If you’ve never been inside the Sydney Opera House, then these shots will give you a pretty good sense of its space and what it means to be able to hear a pin drop down the aisles.

I won’t ruin the surprise of how Gadsby concludes her set, but it is raw, it is poignant, and it is a performance of fire-fuelled rage as she stares down the barrel of the camera and demands action. “Stop wasting my time” she shouts in a blistering exchange that throws Cosby, Weinstein, Clinton, and Louis C.K. into a metaphorical woodchipper. To those who think political correctness has killed comedy, Nanette might just explain why it can also save lives.

The name “Nanette” was the name of a woman Gadsby met and decided to frame a comedy show around. It didn’t pan out. In essence the name then suggests failure, and much of the show’s potency comes from that, whether it be her own perceived failures or those of society at large. She claims this show is her retirement from comedy – decades of self-depreciation has never allowed her to come to terms with what has been inflicted upon her as a queer woman across industries that are dominated by straight men in a society that has tried its hardest to push her to the cultural fringe. “Do you know what self-depreciation means coming from somebody who exists on the margins?” she asks the audience who, by that stage, are well and truly wrapped around her storytelling finger. “It is not humility; it is humiliation.” What a way to go if it’s true.

Gadsby’s Nanette deserves to sit alongside greats of the genre (which once had real box office potential and cultural cachet rather than just streaming filler) by the likes of Richard Pryor, Margaret Cho and Eddie Murphy. In many ways she overtakes them, allowing her comedy to be more than just funny, but a potentially life-changing gift as well.

Reader Comments (5)

Oh I loved her in Please Like Me. Thanks for this, I’ve just googled and it’s not released on Netflix in the UK until the end of this month. I’ll definitely be watching.

Gadsby was often the best part of Please Like Me, and I watched a lot of her stand-up after seeing her in that show, and loved it. I didn't know this was a thing, but I CAN'T WAIT to watch it.

I loved her in Please Like Me. Thanks so much for bringing this to our attention.

I just watched this, prompted by one friend after another raving about it online. I agree with your assessment, Glenn -- and I urge people to make time to watch it.

Yes - definitely watch this. Amazing.