The Art of History and Peter Jackson

Friday, January 11, 2019 at 6:06PM

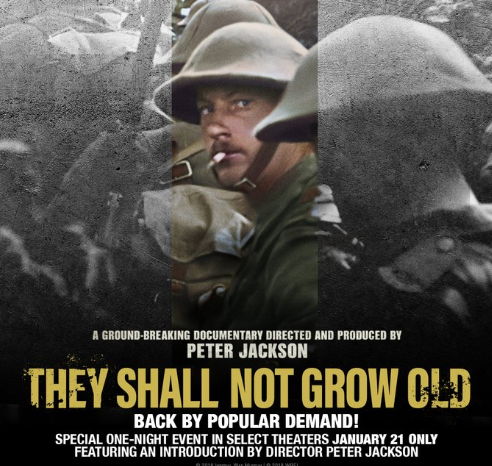

Friday, January 11, 2019 at 6:06PM Please welcome guest contributor Kate Imy to talk about Peter Jackson's WW I documentary They Shall Not Grow Old which is currently screening in the UK, and has an encore Fathom Event scheduled for US cities on January 21st.

by Kate Imy

by Kate Imy

When historians insert themselves into discussions of popular culture it is usually to spoil the fun. I once read a real, straight-faced takedown of Downton Abbey that objected to the horses as ahistorical. Of course, historians can and do bring much-needed context to many discussions of recent films. For example, some have furthered discussions of Dunkirk to bring attention to the presence and involvement of colonial troops throughout World War II. As a film-lover and a historian, I tend to prefer films that throw the pretense of historical accuracy out the window. I’ll take voguing in The Favourite and chanting “We will Rock You” in A Knight’s Tale over a reverential insistence on “accuracy.”

Films that maintain a veneer of historical fact, often distort the truth without admitting that they do so. These often hit the audience over the head with dubious history and overt political messaging (I am thinking of a few recent movies about Kings and Prime Ministers). Some of these will even claim to tell a story “Not in the History Books” (What this usually means is that they don’t bother to read history books). In reality, art and history—when done well—often perform similar goals on different stages. Good art and good history are about finding inspiration and truths about humanity from the past...

My out-of-the-gate slight defensiveness comes from a recent screening of Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old. The Imperial War Museum (London, UK) approached Jackson to make a film using IWM archival materials to commemorate the centenary of the European armistice of the First World War (November 11, 2018). In a making-of featurette that followed the Fathom Events screenings, Jackson explained that he made the movie as a non-historian for non-historians. Never have I felt so unwanted! But in making the film, as Jackson explained in the featurette, he used methods that pulled straight from the historian playbook. He spent countless hours sifting through audio and film in the archives of the Imperial War Museum. Historians do that. He made tough choices about what to include and what not to include. Historians definitely do that. According to the featurette, he tried hard not to insert his own bias or get in the way of his own subject matter. Historians try to do that (more on that in a minute). He traveled around the world and brought in experts to collaborate on aspects of the film outside of his expertise. Historians do that, often without the automatic name recognition and funds that someone like Jackson can command! In short, Peter Jackson played the role of historian with the training of filmmaker and artist. This gives him a unique position to tell the story in some interesting ways.

The film soars when Jackson trusts his artistic instincts. One of the most rightly touted aspects of the film is the restoration and colorization of the IWM’s film archive. This included meticulous efforts to lighten materials that were too dark, or slow down footage that was too fast. Historians everywhere: rejoice! To my viewing pleasure, the colorization was handled with ease and grace. Early sections focused on soldiers’ recruitment and training, narrated by First World War veterans, with black-and-white footage. The colorized footage only appears when soldiers arrive at the front—a result not unlike Dorothy opening her front door to brilliant color of Oz. The vivid greens of trees and fields seem jarring to those accustomed to seeing the Western Front depicted exclusively as a colorless No Man’s Land (my favorite ahistorical depiction of that, by the way, is definitely Wonder Woman). Bloodied bodies and feet afflicted with gangrene inspire greater empathy (and gag reflexes) from the audience. One amazing scene includes soldiers playing instruments, with one sly soldier strumming a glass bottle like a guitar with both deadpan seriousness and a wink behind the eyes. Dogs, rats, and moldy food spring to life to help the audience feel more immersed in the muck and grime of the war.

One of the best and most absorbing sequences of the film is the depiction of a long battle. Some military historians might object that the scene does not specify where or when this takes place. In fact, Jackson admitted in the featurette that the interviews and film footage come from across the Western Front and describe different battles. To me, this is a strength rather than a weakness. Several soldiers narrate the difficulties of being under siege in the trenches, hiding in holes during artillery bombardment, or watching friends die beside them. Jackson cuts quickly from footage used earlier, focusing on the individual faces of soldiers, and then images of fallen soldiers on the battlefield. It is a long sequence and feels almost relentless in the quick jumps from horror to horror, smiling face to mangled corpse. This, I think, is the closest Jackson, or many other works of art, get to capturing the feeling of unending battle. It is nothing short of breathtaking.

Other sequences fall a bit short of this magnificent opus. A less convincing touch in the battle sequence is Jackson’s use of propaganda imagery to illustrate specific battles. As other scholars have pointed out, this proves somewhat distracting and gives us less of a sense of what actually happened than what British officials wanted the public to think about the conflict. Other things, like the descriptions of muddy and filthy trenches, brief mentions of food and weather conditions, or “all in good fun” remarks about prostitutes will not be entirely surprising (or convincing) to anyone who did their obligatory tenth grade reading of All Quiet on the Western Front. In fact, it was somewhat disappointing to see that the director of Heavenly Creatures not go further in exploring gender or sexuality. He might have included imagery of British propaganda about avenging the “Rape of Belgium” early in the war, and juxtapose this with the prostitutes mentioned by British soldiers, who in many cases were French and Belgian refugees. Similarly, he provides no insight about soldiers’ complex intimacies with one another in trenches and in prisoner of war camps. These encounters engendered serious (what we would call homophobic) concerns in postwar societies about soldiers being overly sexualized by the experience. The only slight indication we get of this are cheeky (pun intended) shots of soldiers lining up, bare-bummed, on a log to relieve themselves. The levity was appreciated, but the moment also passed quickly.

If there is to be a major critique of the film it is the decision to focus on British soldiers on the Western Front exclusively. World War One adorns cinema screens far less than the Second World War, but those that consider it generally show us trenches in Belgium and France. This film is no exception. A few films have done much with other fields of battle: Lawrence of Arabia and Gallipoli famously provided glimpses of British imperial campaigns against the Ottoman Empire. Theeb (2014) reversed the gaze to show audiences the war from the perspective of a civilian boy in Hijaz (western Arabia) who witnessed this grand imperial cataclysm. In his featurette, Jackson explained that his focus was deliberate: he wanted to give audiences a sense of experience of an average British (specifically British) soldier on the Western Front. This is due, no doubt, to funding from the Imperial War Museum which commemorated the armistice mostly for British audiences. This is somewhat of a missed opportunity since Jackson himself (and his grandfather who served) is a New Zealander “kiwi” which hints at the larger imperial dynamics of the war. Further, Jackson explained that, in sifting through the collections, he wanted to remove his own “bias” and let soldiers tell their own stories. If he had included other topics, such as colonial troops or women, he suggested, this would have been too much to cover in adequate detail. While this did allow him to tell a more focused story, it makes him miss important points about the nature of the conflict, the complexity of national identity, and why and how we tell stories about war.

First, there was no “average” British soldier: differences of rank, region, ethnicity, age, religion, and class shaped soldiers’ experiences. For example, Irish soldiers joined the British Army in large numbers. Can they be understood as part of the general “British” experience of war on the Western Front? What about Private Jogendra Nath Sen, who joined from Leeds but was born in India? British women, similarly, served as nurses, ambulance drivers, and members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, giving them experiences of war similar to the “average” British soldier. Jackson also admitted that he compiled his “average” soldiers’ experience by looking for similarities in veterans’ interviews. He brushes over the fact that these were recorded decades after the conflict ended. Overlaps may have had less to do with their shared experiences than in the streamlining of memory over time. Anyone who has ever listened to an elder family member’s war stories (my deepest sympathies!) knows to take such accounts with a grain of salt. Soldiers’ interviews are no different. Many tell the same stories year after year because they know that those are the stories that people want to hear. Interviewers shape the topics that they cover. Their own memories of the war have been distorted by sharing or reading tales—sometimes exaggerated—with other soldiers, newspapers, or memoirs. Historical actors who “were there” are not immune from changing their perceptions of events based on reading poems, analyzing paintings, or seeing films.

Peter Jackson behind the scenes

Peter Jackson behind the scenes

Art matters, and it shapes history. Historians, like me, remind our students that there is no such thing as a perfect source. Each time we make choices about what to include or what not to include, we are inserting ourselves into the story. What we care about becomes what the story is about.

Artists, including Jackson, ask us to find the humanity of our subjects to better understand the visceral, human experience of war. Art gives us a nearly unparalleled opportunity to immerse ourselves in other worlds and feel the pain of people different from ourselves. In They Shall Not Grow Old, this lends itself to some beautiful moments: such as showing audiences friendliness, empathy, and common experiences between British and German soldiers. No less important is recognizing that similar things happened with Indian, Nepalese, Senegalese, Russian, Chinese, Algerian, and Australian soldiers and laborers who had similar—and different—experiences.

None of this is surprising to those who have spent time in the Imperial War Museum’s collections. Medals, uniforms, propaganda, photographs, and films exist for the millions of soldiers (1.4 million combatants and non-combatants from India alone!) from around the world who served on the Western—and other—Fronts. Not including them in They Shall Not Grow Old was a choice, however well-intentioned. The First World War is famous for the battles in Belgium and France. Yet its battlefields stretched from East Africa to Singapore, Gallipoli to Samoa. It ended with the rapid expansion of the British and French Empires. Historians don’t just tell people to get the names and dates right. We also remind audiences that a lot of different people were there, too. Their experiences are also deserving of empathy, commemoration, and analysis.

Definitely see They Shall Not Grow Old. But also, take a look at the online collections of the Imperial War Museum, or read a recently-written history of the war. Both art and history can make us feel inspired about and connected to the stories of the past and the complex world in which we live in the present.

Kate Imy is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of North Texas. Her book "Faithful Fighters: Identity and Power in the British Indian Army" is forthcoming with Stanford University Press. You can read one of her articles about British and Indian Muslim soldiers here.

Reader Comments (3)

Thanks for this fascinating read. I really want to see the film. (I'm British and somehow I managed to miss it both in cinemas and on TV, but at least it's now out on disc.) What a great collaborative moment between an esteemed filmmaker and an esteemed museum.

This is by far the best critique of Jackson's superb ( and it is superb) film that I have read. Most reviews have been by film critics and not historians which makes this rather more interesting. You mention the interviews that Jackson used in the making of the film. As you probably know, these were made in the late 1950s and early 60s for the BBC's seminal documentary "The Great War" which was the first of a run of great documentaries made in a similar style, including "The World at War" and Ken Burns's "Civil War". As you correctly pointed out, these suffer from what the late, great John Keegan in his highly influential "The Face of Battle" called the "Bullfrog" effect. The old soldiers had stories to tell (I noticed that the poet Edmund Blunden was one of those interviewed), a fact reinforced by the fact that there were two VC winners listed at the end of the film (by definition a VC winner had a story to tell!). So the voices used were slightly self-selecting.

As far as the subject selection was concerned, I suspect that Jackson was limited, especially for the scenes shot as close to the front as possible, with what was available. Many would have recognised the Beaumont Hamel mine going up and the sunken lane with the Lancashire Fusiliers about to attack. Both scenes were shot within a few minutes of each other by Geoffrey Malins on the catastrophic 1st July 1916. (Many of the soldiers shown would have been dead within 20 minutes of that scene being made [ I nearly said "shot"]) . They are iconic images of WW1 and I doubt that there are too many other film scenes taken as close as those were to the battlefront.

Yes: the film was commission by the IWM ( with funding from the UK government) to commemorate the end of the war and is the story of the British Tommy in that disaster, It isn't the history of the Canadians, the New Zealanders, the Aussies, the Indians, the BWIR etc. They all played a massive part in the war (the Indians, for example, plugged a massive manpower gap in the Western Front throughout 1915), But it isn't their story..

Thank you so much for this. It was a fascinating read. I knew if I were to cover it it’d be entirely ill informed. HAVING SAID THAT, this film gave me the whim whams while at the same time announcing itself as a boldly ambitious effort. The colorization and animations are impressive but often produced a strange effect of rendering a lot of the footage as fake or, I guess, like a movie. The colours seemed off for starters, like a 1980s British television series. And the reframe animation technique offered some strange effects to the footage that took me out of a documentary headspace.

I would love to see the technique used, however, to perhaps tape up classic silent movies. There’s value to it.