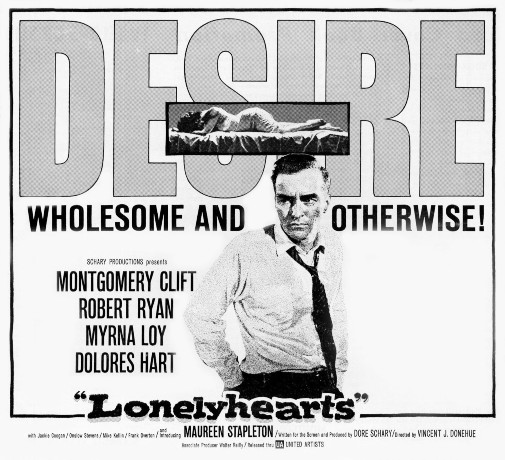

Monty @ 100: The martyrdom of "Lonelyhearts"

Monday, October 12, 2020 at 7:00PM

Monday, October 12, 2020 at 7:00PM

For the first half of his career, Montgomery Clift typified an image of restless youth and tragic beauty onscreen. Many of his early films found Clift playing young traumatized soldiers or men embroiled in doomed romance, lively characters whose nervous energy electrified the frame. The second era of Monty films, starting with 1957's Raintree County, saw a transformation of his persona. Nathaniel previously explored some inklings of masochism in the narratives of From Here to Eternity and The Young Lions, but Clift's next few projects solidified him as a paragon of cinematic suffering.

Perhaps no project better encapsulates the idea of Montgomery Clift as a saint-like figure, a martyr, than the Vincent J. Donehue's 1958 film Lonelyhearts…

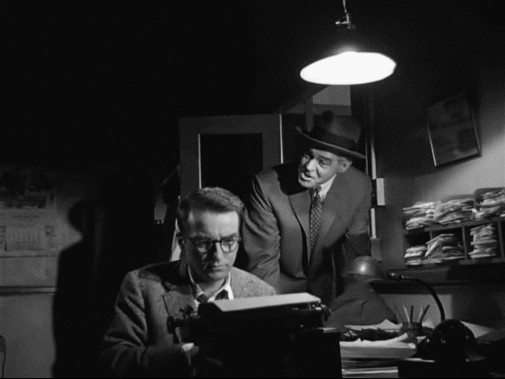

In 1932, Nathanael West wrote what would become one of his most influential and acclaimed works. Published the following year, Miss Lonelyhearts is a black comedy set during the Great Depression, a sorrowful tale about a newspaperman who writes the titular column. Scorned by his colleagues who find the work mockable, the unnamed journalist lets himself be burdened by the pain of the lonesome and loveless souls who write him letters, seeking advice. The man's gloom isn't helped by the malicious manipulations of his editor, a cynical fellow who has no patience for Miss Lonelyhearts' feelings of responsibility to his readers.

There's a nihilistic sheen to West's plot, as Miss Lonelyhearts tries to escape the misery of the letters through any means possible, including sleeping with one of the readers who write him. That last bout of stupidity ends up costing him a great deal. The reader, trapped in a loveless marriage, insists on the attention of Miss Lonelyhearts and, during a bizarre evening when the journalist's invited to his lover's house for dinner, he beats her. Bruised and brokenhearted, the woman tells her ailing husband that Miss Lonelyhearts raped her and, in a fit of vengeful fury, he confronts the writer with a gun. In the end, Miss Lonelyhearts embraces his assailant in a fit of religious folly and the two meet their demise together.

It's an alienating read, cynically amusing, and razor-sharp in its social critique. No wonder it was so popular, gaining a cultural cache that's as enviable as it is daunting. Hollywood quickly worked on a movie adaptation, releasing Advice to the Lovelorn in 1933. The plot is heavily changed and the conclusion's misery mutated into a ghoulish happy ending. Later, in 1957, Howard Teichmann wrote a more faithful dramatization of the story in the form of a play that failed to take Broadway by storm. It ran for a mere twelve performances at the Music Box Theatre.

Strangely enough, it was that theatrical failure that prompted a new movie adaptation of Miss Lonelyhearts, now simply titled Lonelyhearts. Producer Dore Schary had recently left MGM and this movie was to be his first project as an independent filmmaker. Whatever dark humor was to be found on the original novella or its play adaptation, Shary and co-screenwriter Leonard Praskins made sure to excise from the script, making for a doom-laden drama whose congealed despondency threatens to asphyxiate the viewer.

Still, like the '33 movie had done, this new Lonelyhearts chooses a happy ending over the novella's original denouement. It makes for a story that, instead of being a cynical social critique is more akin to a moralistic sermon. In many ways, that difference illuminates other trends and artistic norms. It's the contrast between daring literature and populist entertainment, between the cultural mindset of the early 30s and the new conservatism of the Eisenhower presidency. The actors, for their part, follow the ethos of this stern reading, abandoning any hint of subversion, silencing the whispers of cruel laughter, and enrobing themselves in sanctimonious righteousness.

You might have guessed it from my words but, let's be clear, Lonelyhearts '58 is a disappointing failure, interesting in its misery but hardly revelatory. The legacy of West's writing overshadows the adaptation, its concentrated agony, and willful provocation neutered beyond repair. More than anything, the picture fascinates as a challenge for its cast, a demanding acting exercise that results in a couple of inspired performances and some less successful efforts that are, nonetheless, worthy of discussion. As the venal editor, Robert Ryan is the MVP, injecting caustic malice into the film's moribund organism with such verve one almost feels the burning hatred of his words heating the screen.

As the editor's alcoholic wife who's forever punished for her adulterous past, Myrna Loy shows that she was capable of adapting to changing paradigms of acting. There's an old-school archness to her performance of pitifulness, but the actress knows when to open the floodgates of real emotion and drown the film in self-hatred. As for Maureen Stapleton, the recipient of Lonelyhearts' only Oscar nomination, she chews the scenery with inchoate abandon. Playing the wanton reader who ends up a victim of Miss Lonelyhearts' canker blossom ways, Stapleton takes control of every scene with the voracious hunger of a starving lioness. Whenever they share the screen, she steamrolls over Clift without ever breaking a sweat.

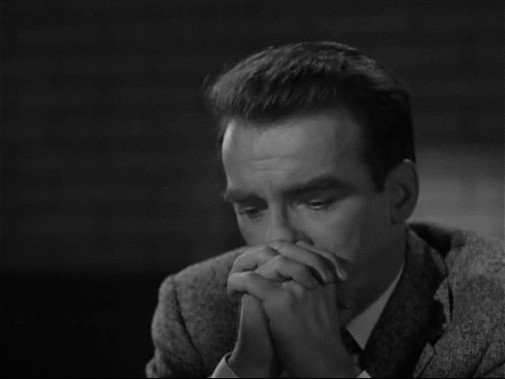

Regarding the actor whose centennial we're celebrating, Montgomery Clift is reduced to a reacting fixture in comparison to his fellow actors. It's not so much that he's overshadowed by them, but the script insists on making the journalist, now named Adam White, into a saint-like figure who only wants to help those less fortunate than him. Clift is asked to be vulnerable and he does it with ease, transforming into an emotionally open wound before our eyes. His heart is exposed in every scene and every sense, the bloody flesh spasming in pain, and the brittle bone uncovering its marrow for the viewer's pleasure.

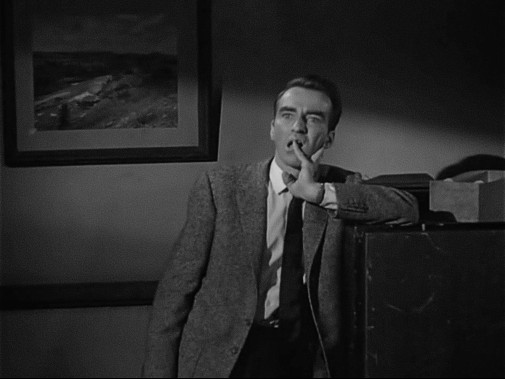

One can't deny that Clift is in tune with the screenplay's tonal wavelength, though he's perhaps too consistent in his mirthless angst. The many scenes when we see Adam agonizing over the Miss Lonelyhearts letters become repetitive after a while and the actor does next to nothing to combat that redundancy. Furthermore, he's unable to make sense of Adam's decision to sleep with his faithful reader. Because the script forces the novella's protagonist into being a martyr suffering for all of Humanity's sins, his amoral decisions come off as motivated by nothing but the predetermined mechanisms of the plot.

All that said, Clift's acting impresses with its intensity, its abrasive sense of sorrow exploding outwards, and virtuous mask of despair. I'd genuinely love to see Monty portraying the nameless journalist of the novella rather than Adam White. Perhaps a better director would help too. For as much as it's possible to recognize greatness in the film's cast, the Lonelyhearts actors often feel as if they each belong to a different movie. They require a stricter hand to mold their performance styles into a cohesive whole. Clift was also in desperate need of guidance, someone that could dissuade him from falling into mannered ticks. His hand acting is of particular concern, often reading as an actorly crutch which grows distracting as the drama unfolds.

Montgomery Clift still had some great performances in his future, but Lonelyhearts is a misjudged miasma of misery porn twisted in the form of a morality play. It's far from essential, though its importance as Maureen Stapleton's first big break gives it some invaluableness. Now that I think about it, Clift was quite the lucky charm for his costars as far as Oscars were concerned. He made only 17 films, but those features amassed 14 acting nominations (4 who won) besides Monty's quartet of losing nods. And that doesn't even cover Ivan Jandl's juvenile award for The Search. It's a pity that the good fortune never reflected on him. After all, Clift would end with not a single little golden man of his own.

Tomorrow: Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

Reader Comments (7)

As far as Monty's involvement goes this is a real disappointment.

It's been a few years since I've seen it but I still clearly remember Robert Ryan's brilliant venality (how ironic that he like Richard Widmark was so adept at playing loathsome men when both were known to be two of the kindest, most liberal men in the business), Myrna Loy's sharp work, Maureen Stapleton's showy performance and the fetching grace of Dolores Hart and almost nothing of Clift's work.

It was very much a downer so I'm not in any hurry to renew my familiarity with it either but I do remember that this is the first time in a film I thought Monty really looked old beyond his years even if he was playing a more age appropriate character than in The Young Lions.

Re-watching now...

(Thanks in advance for that seventh screenshot above. I think it's the first image of post-accident MC I've ever seen—and I've seen a lot—where his 38-year-old face looks like it might have had there never been a car crash.)

I've only seeen this once -- primarily for MAUREEN STAPLETON but remember loving Myrna Loy in it also. But don't remember Monty's work which is something because i usually remember him even when the work isn't great (remember him well in Suddenly Last Summer for example) . of course it's easy to remember him when the work is sensational.

I ended up liking this film, despite the bizarre shift of Clift’s character sleeping with Stapleton’s, although now knowing the context of the source material, I guess it falls in line with the softening of the material. Loy was really memorable, and Hart had a very sweetness to her (I’m interested to see more of her films). Clift was solid here, although not as memorable.

After just finishing a rewatch, I have to disagree with Cláudio about the martyrdom factor in Lonelyhearts. Although I've been writing in the comments to posts in this series that it's a predominant element in MC's film persona, it's actually muted here. Sure, guilt and saintliness abound, but when I talk about Martyr Monty, performances like the ones in The Young Lions, From Here to Eternity, The Misfits, Wild River, even A Place in the Sun come to mind before Lonelyhearts. I'd even put Raintree County (for meta reasons as well), I Confess, Judgment at Nuremberg and Stazione Termini (that fall from the train at the end!) higher on the martyrdom scale.

Other than that, I enjoyed the film and Monty's work in it much more this time around. (I had to forget West's novel, of course.) I was also struck by how well the lighting and black-and-white camerawork softened his face to its pre-accident beauty, as seen in a couple of the screenshots above. Nonetheless, he seemed too old for the role (and, at 38, to be paired with Dolores Hart, who was 18 years his junior, almost to the day). Just eight years prior, he had been believable as more or less a teenager in A Place in the Sun.

Excellent review and analysis of a film that should have been far better than it was. I wish Monty had a stronger director. His brand of anguish could feel repetitive without a strong hand to guide him.

What a wonderful essay on this hard to locate film. Never released in the US on DVD, it remains difficult to track down, but I did find a VHS copy in the library (before they all but vanished (like other Oscar nominated films criminally never released on DVD Or Blu-ray here: The Crowd, The Bachelor Party, The Fixer, White Banners, Last Summer, The Mating Season, Looking For Mr Goodbar, Tribute, etc). I wish the Academy would take up the cause of preserving and making available these titles, however dated some may be. And finally, Kino is releasing 2 of these titles commercially: Freud starring Monty, and at long last, Diary Of a Mad Housewife, starring Oscar nominated Carrie Snodgrass