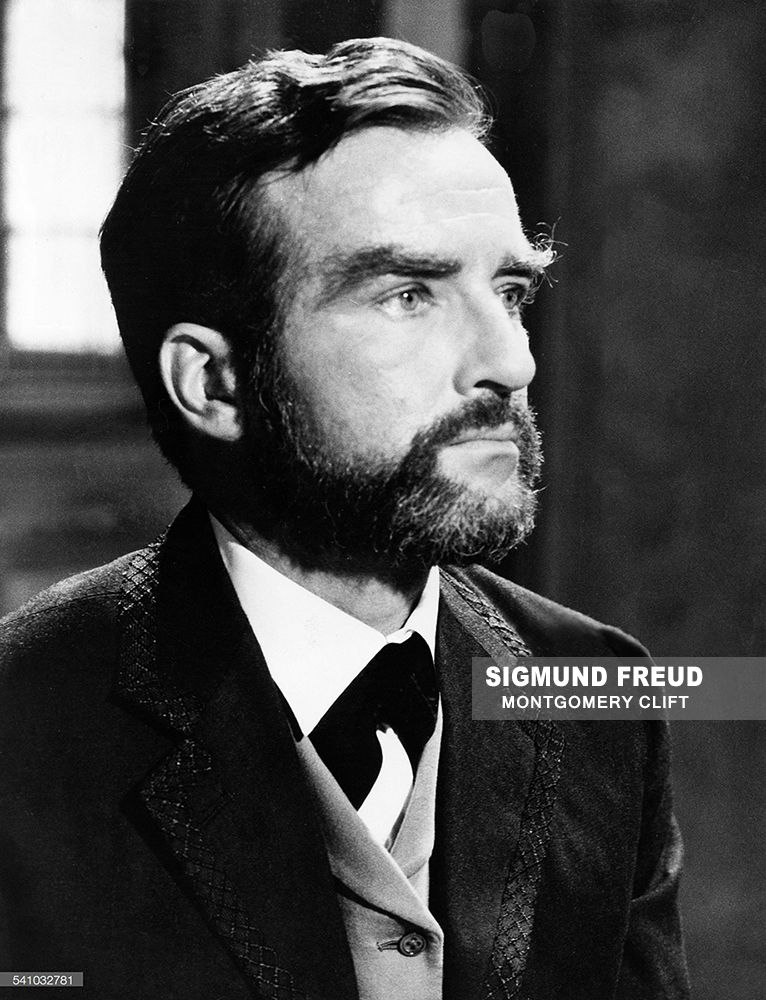

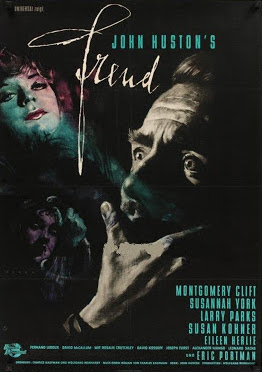

Monty @ 100: John Huston's "Freud"

Saturday, October 17, 2020 at 8:00PM

Saturday, October 17, 2020 at 8:00PM

by Daniel Walber

Freud: The Secret Passion (1962) is an odd movie to categorize. It has the moody pessimism of the late ‘60s and the earnest hero-worship of a biopic from the ‘40s. It’s Montgomery Clift’s second-to-last film, but it doesn’t have the “end of an era” energy of its immediate predecessors, The Misfits and Judgment at Nuremberg. In terms of Oscar history, it feels perhaps most significant as Jerry Goldsmith’s first nominated score. And practically no one has seen it.

But I’m here to tell you that’s a shame, because Clift was perfect for Freud. I’ve realized this over the course of the past couple of weeks, reading everyone else’s fabulous Monty @ 100 coverage. Freud is, in a sense, the ultimate fusion of two essential parts of Clift’s star persona: the heartthrob and the priest...

Nathaniel talked about this quite a bit in his piece on Red River. Clift was the first of a new wave of male stars, bringing a softer and more fragile masculinity to the screen. This quietly transgressive beauty won him both adoring fans and pigheaded enemies. And so, perhaps as an inevitable corrective, Clift also winds up in the presumed-sexless roles of priest and psychiatrist in I Confess and Suddenly, Last Summer. The tension between his soft sexuality and its rigid opposite makes him the perfect Freud.

It also helps that the movie isn’t really a biography. Freud focuses on just a few years of the doctor’s early career, beginning in 1885. It was adapted from a script by Jean-Paul Sartre, who reportedly quit the project after director John Huston refused to make an 8-hour movie.

The opening narration compares Freud to Copernicus and Darwin, men whose theories remade the world. Yet the film that follows is much less bombastic. Clift plays Freud as curious rather than confident, utterly convinced that the governing explanations are wrong but still searching for an alternative.

He observes, mostly, waiting for something or someone to trigger a revelation. Huston keeps Clift close to the patients, denying any clinical distance and approaching the compositions of Ingmar Bergman.

Freud often feels like a horror film. Part of that is Goldsmith’s score, pushing beyond comfortable tonality. Part of it is the use of darkness and shadow, in both the dream sequences and the over decorated drawing rooms of the Vienna bourgeoisie. But the driving force of anxiety and fear is Clift’s eyes. It is as if Freud perceives his own work as a haunted house, a shock around every corner. His patients haunt him like ghosts.

Freud’s colleagues see “hysteria” and other unexplained phenomena as merely an inconvenience, one caused by the lies of impertinent patients. Freud knows that they’re wrong, the truth continues to elude him. The human mind is “a region almost as black as hell itself,” as the voiceover narration puts it, into which he must tread.

The thing is, he can’t just shine a light into the subconscious by peering at his patients. He also has to turn inward. The more he learns about trauma and its effects, the more he recognizes his suspicions in himself. His own dream sequences become just as important as those of his patients, if not more so.

Every fright inspires him to push further. His eyes open wider and wider, as if dread itself were the engine behind his brilliance. He is terrified that he might, himself, be Oedipus as well. But he is even more afraid of not uncovering an answer. His work is a haunted mirror, from which he cannot turn away.

Eventually he arrives at the revelation that there is sexuality in childhood. “The innocent is born into a world in which it cannot help but lose its innocence,” he explains. It is an assertion that will appall the entire psychiatric establishment, including his most trusted colleagues. But Clift plays it as if their objections barely register, appearing more bored than indignant. After trekking through hell without a map, why would he be afraid of a bunch of stuffed shirts? His fight for recognition seems almost immaterial compared to the actual work of psychiatric spelunking.

It is a revelation tailor-made for Clift, a partial resolution to years of embattled sexuality and contested stardom. The priest and the doctor have just as much sexuality as the heartthrob. They are, after all, the same man. They always have been.

The ending of Freud is almost shockingly bleak, given the hagiography with which it begins. Freud does not win. Nor does Huston hold out his eventual recognition as a happy ending. Knowing more about the world does not necessarily make it a better place to live. Freud’s ideas, like Darwin’s, have spawned their fair share of monsters.

But back to Clift. Has the psychology and sexuality of stardom changed since Freud? The dichotomy between the sexualized and the sexless movie star certainly hasn’t evaporated. If anything it’s become starker, particularly now that Disney seems to own everything. Could an actor like Clift be nearly as famous today? I’m not so sure.

Next: Clift's final film, The Defector (1966)

Reader Comments (11)

I was wondering how I was going to see this since it wasn’t readily available, but luckily it was available on Archive.org for anyone interested. It’s an interesting film, which surprised me with a lot of the horror elements. Alas, it felt it’s running time and while I appreciated Clift’s many reactive shots to the patients and the other Doctor, I kinda wanted more from the film. By the time we get that amazing monologue towards the end, I was happy for it, but then the film soon ends.

When I first saw it, what I liked best was the Jerry Goldsmith score! I recognized the main title cue as well as others being effectively used in "Alien" (1979). Official "Alien" soundtrack album hasn't those tracks so I immediately bought the "Freud" soundtrack CD. Ironically Freud himself would probably have something to say about being associated with H.R. Giger's phallic creature. Strange film, but excellent music.

Great post, I never thought of the film that way, but the priest-love object analogy is perfect. I really liked this film, although I found the John Huston narration bizarre. That said, Clift's Freud has tremendous humanity which balances out his clinical side. I have wondered if the actual Freud had that warmth? Either way, I enjoy that characterization.

Interesting take on this obscure picture.

This is one I've only watched once and it was quite some time ago. It seemed interminable at the time which is why I never went back to it but what I recall of Monty's work left a positive impression.

When I was a kid, the name "Montgomery Clift" always evoked some older, bearded man, maybe a Southern general, maybe a professor or doctor. It wasn't until I was a young adult that I was introduced to the actual, iconic "Monty Clift" of the late 1940s and early 1950s. But now it hits me that Freud was the only MC film that got a lot of play on TV when I was a kid. I think I tried to watch it once and was bored by its subject matter and length and that bearded man in the title role. Little did I know.

I haven't rewatched it yet, because I'm bracing myself to watch The Defector for the very first time tonight...

"After trekking through hell without a map, why would he be afraid of a bunch of stuffed shirts?" "Knowing more about the world does not necessarily make it a better place to live. Freud’s ideas, like Darwin’s, have spawned their fair share of monsters."

Absolutely tip-top review, Daniel! Beautiful to read, insightful, and an accurate take on the film if my memory (one viewing over 20 years ago) serves. Of course, it bears noting that the film isn't a particularly accurate account of Freud's life, or, rather it's not really a good representation of it, even keeping in mind its focus on his early career.

A good piece of news dropped a couple of weeks ago. The film is finally coming out on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber in a new restoration. Date not set, but sometime in 2021.

I just found this, Madonna and Montgomery Clift together:

https://youtu.be/PrLagZftero

The film does play like a horror film,I think Clift is exceptional,A truly great swan song if you forget about The Defektor.

In a taped phone conversation with his brother, Brooks Clift, Monty warryingly tortured drunk claimed that his long overdue Oscar would arrive with 'Freud'. He was so excited and so sure about that... he seemed lost...and sadly he didnt get the recognition he deserved in his entire career.

Finally, this film will see its US DVD debut soon, as announced on the Kino-Lorber web site. Now will anyone secure the rights to “Lonelyhearts?” If not for Monty, at least for Maureen Stapleton’s first Oscar nominated performance?

I alws find it ironic tt the Golden Globes nom Susannah York for Best Actress Drama (she wasn't even mentioned at all in above review), but can't find a place to nom Monty in its expanded 10 slots for Best Actor Drama!

I guess at this point, Hollywood has officially given up on Monty 😔