The Furniture: Of Tesla and TED Talks

Wednesday, September 9, 2020 at 10:00AM

Wednesday, September 9, 2020 at 10:00AM "The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

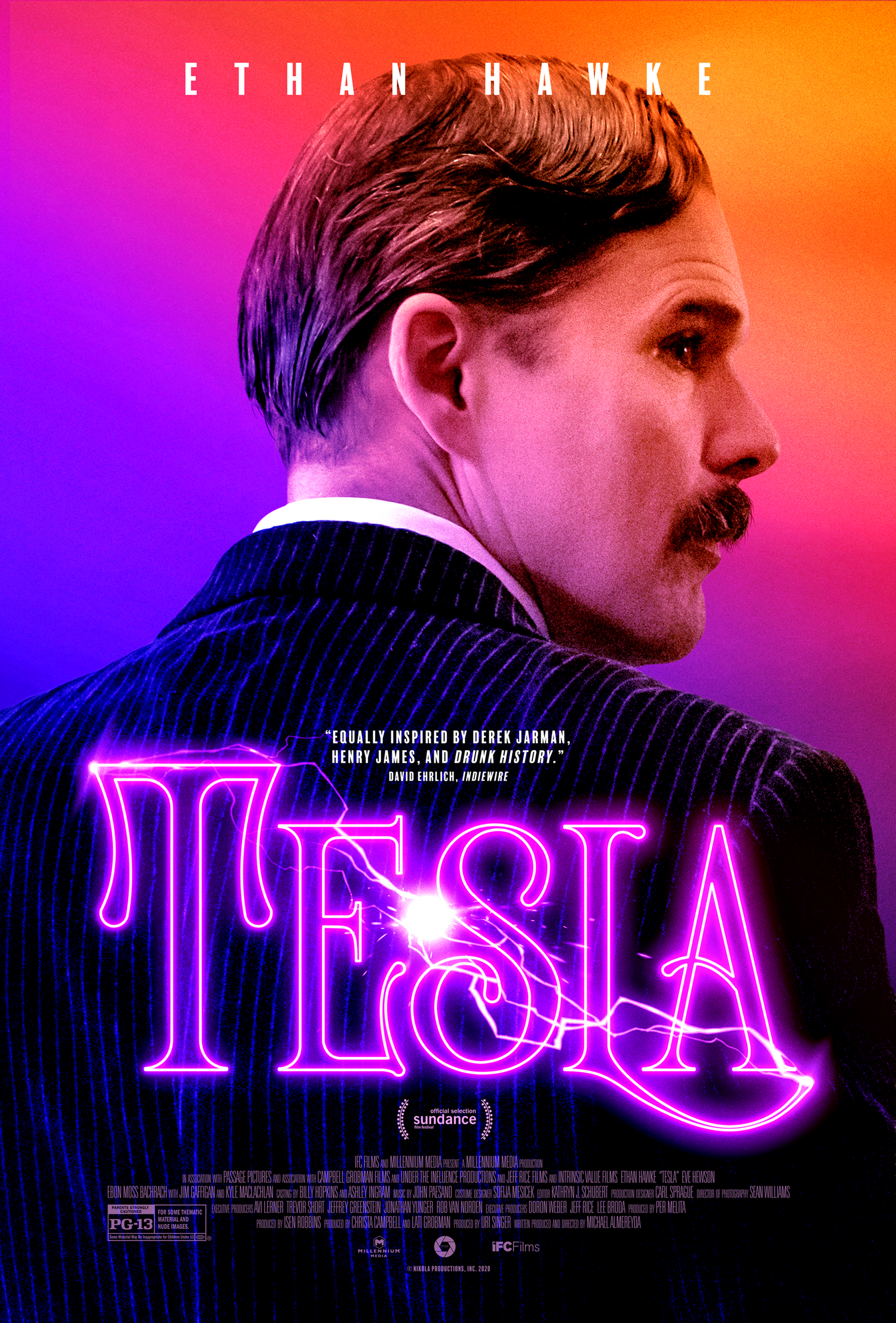

Does genius have an aesthetic? And what would it look like? Tesla poses this question in a big way, tossing out the visual parameters of a typical period piece in the process. Director Michael Almereyda has said that he was inspired by “Derek Jarman, Henry James and certain episodes of Drunk History,” which absolutely comes through - and is a good thing. But, to be honest, Tesla also reminded me of a major component of the 21st century tech aesthetic: the TED Talk.

Does genius have an aesthetic? And what would it look like? Tesla poses this question in a big way, tossing out the visual parameters of a typical period piece in the process. Director Michael Almereyda has said that he was inspired by “Derek Jarman, Henry James and certain episodes of Drunk History,” which absolutely comes through - and is a good thing. But, to be honest, Tesla also reminded me of a major component of the 21st century tech aesthetic: the TED Talk.

It’s in the script, too. The first thing we hear is a tale of the title inventor’s childhood, told by our narrator Anne Morgan (Eve Hewson). The young Tesla once noticed static electricity on a cat, a little memory that will be woven into an origin story for genius. This is immediately followed by a scene in which Thomas Edison (Kyle MacLachlan) waxes poetic about his own memories, which include an early boat ride on Lake Ontario and witnessing a friend drown shortly thereafter.

Anecdotes like these are the bread and butter of the TED Talk, stories that grab you and make you feel as if you've really learned something about human achievement. Another big trope of this brand of infotainment is the “Big Fact,” a simple detail that is supposed to really bring home a point. Like, for example, the number of Google Image Search results for Edison, Tesla, and George Westinghouse.

Anne is constantly giving us updates like these. She seems to hang out beyond time, Googling on her Macbook and tossing relevant images up onto her projector screen. She is, in a sense, giving us a 100-minute TED Talk about the genius she knew best, Nikola Tesla (Ethan Hawke). And she gets to ask Tesla the biggest question herself: “Is it better to be vindicated or to be loved?”

All of that said, Tesla’s frequent use of 21st century gadgets isn’t just a cheap way to compress narrative with message. This isn’t an Adam McKay movie. In fact, the anachronisms are something that Almereyda takes most directly from Jarman, a filmmaker more people should emulate. This technique has an elegance that comes from its simplicity, a conveniently inexpensive choice to reject the construction of a fully-realized universe and benefit other ways of meaning. It’s no less cinematic, it just means that production designer Carl Sprague and set decorator Tricia Peck have different things to do.

Much of that work involves the interplay between historical props and projected backgrounds, which gradually escape Anne’s domain and enter the story proper. An early childhood memory sees Tesla and his mother at an antique wooden table, reading in front of a projected forest.

Later, the adult Tesla struggles to clean his dishware at a fancy restaurant, though it appears quite empty behind him.

Do the projections hint at a technological future that only Tesla can see? Or do these still images represent his distance from his own world, a 19th century that doesn’t understand him? At one point he even tries to physically break through this constructed boundary, offering an apple to a projected pony.

The handful of physical sets, meanwhile, are built without much concern for realism. They don’t necessarily call attention to themselves as sets, mind. But they have a simplicity that implies a certain bare theatricality, almost abstraction. Edison’s lab is represented by a single brick wall, a few tables, hanging wires and an elaborate electric light fixture.

The execution of William Kemmler is the same, the electric chair backed by another lone brick wall. It could just as easily be the inside of Auburn Prison as the back of a Broadway stage.

Even the more detailed sets are obscured in one way or another, like this banquet hall at the Chicago World’s Fair. The lights lend everything a dreamlike haze. Our focus is briefly drawn to the vacuum in the back, powered by Tesla’s alternating current. Aside from the Orientalist columns, the space could be the ballroom of a chain hotel or convention center - where I have always assumed most TED Talks are filmed.

When Tesla heads out to Colorado, any minor feints in the direction of period detail and realistic set design fall away. The warning sign for his lab might as well be the sign from a treehouse on the soundstage of a children’s show.

Within, Tesla further approaches the porous, shimmering boundary between human perception and scientific possibility. He reads by the blue light of natural electricity, surrounded on all sides by a futurist geometry of light wood. The assertion seems to be that this is where it all culminated for Tesla, where he made his greatest breakthrough - or where he finally fell off the deep end into science fiction.

The difference between the two is entirely a matter of perspective. Tesla ran out of J.P. Morgan’s money and died in obscurity. Recognition took years, but it did come eventually. Today there’s a Wikipedia list of things named after him. That said, you don’t go right to his page if you type “Tesla” into Wikipedia. You’re shuffled to a disambiguation page, which asks you if you’re looking for the deceased inventor or for Tesla, Inc., the project of another self-proclaimed tech genius (one whose antics perhaps more resemble those of Edison, but whatever).

Tesla is now both a man and a brand, fully embraced by the Silicon Valley culture of branding, self-promotion, the tiny microphone and the TED Talk. Maybe Tesla is now both vindicated and loved. Perhaps he exists equally in historical reality and in the ahistorical ether of human perception, which in turn tends to perceive history as images and anecdotes. Tesla’s final set fully opens the door to a space beyond. But is it just a glimpse of a soundstage, or a portal to another dimension?

Reader Comments (3)

okay now i actually want to see this even though i haven't been crazy interested in Almereyda's work.

Interesting approach, though I think your analysis is more worthwhile than the film itself. I was intrigued by the stoic scenery and other devices used here but ultimately it just didn't work for me. I actually found The Current War: Director's Cut, which spotlights a lot of the same events and characters, to be a better version of this story even if it was relatively standard.

Just knowing it was a biopic with Ethan Hawke (rarely the most exciting prospect) meant I hadn't given this one much thought. But after the director's Jarman reference and your confirmation of it does make me somewhat intrigued.