Sundance Review: Ailey

Wednesday, February 3, 2021 at 2:00PM

Wednesday, February 3, 2021 at 2:00PM

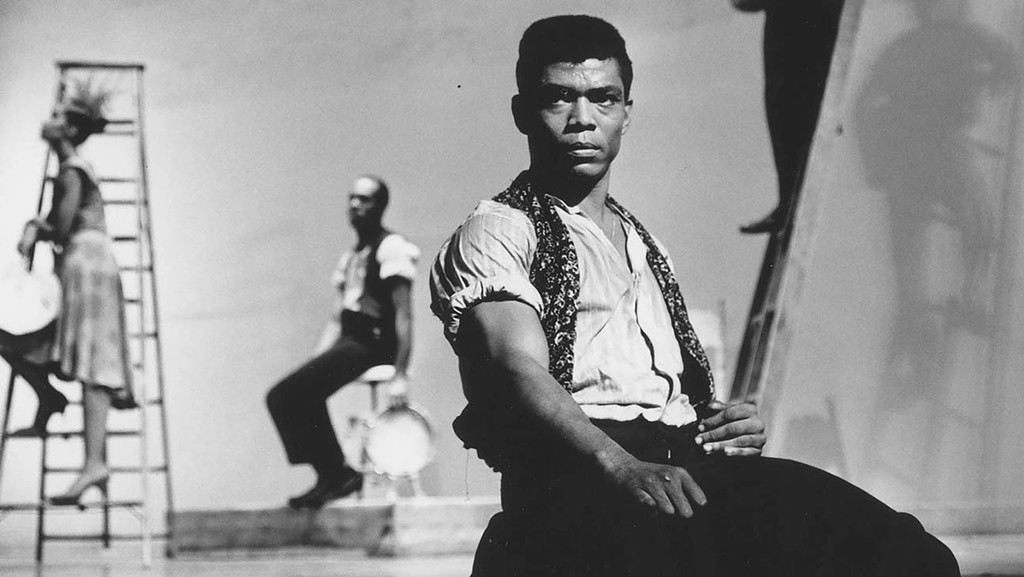

Like Summer of Soul, Ailey tells the story of Black art through testimonials from the artists who lived through it. In this case the story of pioneering dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey. He was only 27 years old when he founded what would eventually become one of the most renowned dance companies in the world; the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater...

Ailey died from AIDS in 1989 so while this documentary includes his words and voice recorded through the years, his story is told through the people who were around him. Friends, dancers from his company, other artists who were his contemporaries and the stage manager of his dance company. Director Jamila Wignot blends all this with archival footage of Ailey’s dance creations. So as we are watching the dances, we hear artists talk about the inspiration behind them and the work they had to put in to make them happen. Historical context is provided through recollections of the dance troupe travelling through a segregated America in the 1960s. Alvin was not just a dance pioneer, for a long time he was the only Black artist known for dance. We hear that in his recorded voice as he talks about growing up in Texas and looking for Black role models in the worlds of dance and opera; his two passions as a child.

The man behind the choreography is not explored much. The stories by the dancers in his company only spark when they are describing their contributions. What they say about Ailey - mercurial, committed, tough on himself and others - could be about any successful artist with a rigorous work ethic. What this documentary shows is how elusive a personality Ailey was. His relationship with his mother is recognized as key, both as inspiration and driving force. You hear his voice talking about her beauty and what she had to go through to raise him - cleaning white people homes in Texas - and that’s one of the few times the film gets close to Ailey. Even his voice talking about a lover who abandoned him one day without notice sounds remote. Perhaps that’s a part of his life he didn’t want to share and Wignot respects that and doesn’t pry much.

Ailey never spoke of getting sick of AIDS. Here we get to see the last few months of his life through the usual talking head recollections about losing weight etc. Then Bill T. Jones appears and with righteousness and clarity says that perhaps Ailey wasn’t able to talk about AIDS because he didn’t have many gay people around him. That being “the one” anointed by white America as the representative of Black people in the world of dance somewhat isolated him. That’s when the film comes to life, Jones gives us a glimpse into the intersection of dance culture, systemic oppression and Ailey himself that has eluded all the other people who spoke in this film. No matter though since by the time we get there we have seen so much of Ailey’s choreography in archival footage. We’ve been lifted by it and understood the enormity of his talent and legacy.

Ailey,

Ailey,  Alvin Ailey,

Alvin Ailey,  LGBT,

LGBT,  Sundance,

Sundance,  dance,

dance,  documentaries

documentaries

Reader Comments (2)

I sincerely hope there's some mention of Katherine Dunham in this film's narrative.

Eagerly anticipating Barry Jenkins' interpretation of his life.