Review: The Great Movement

Monday, August 15, 2022 at 11:38AM

Monday, August 15, 2022 at 11:38AM

In 2016, Bolivian director Kiro Russo took his first feature to Locarno, where the Jury for the Golden Peacock presented him with a special Centenary Award for Best Debut Film. Dark Skull was an exercise in modern Neorealism, reinventing that movement from Italian cinema to a Latin American setting and deep-rooted specificity. More in line with the operatic myth of Visconti's La Terra Trema than with De Sica's urban melodramas, the film followed Elder's return to his desolate hometown upon his father's death. With the patriarch fallen, the son takes on his work, going into the mines like those before him. Those shadowy realms become the entrails of a cavernous titan through the gaze of Russo's camera, the industrial work shattered into a nightmare by mad editing, expressionist sound.

Underrated and under-discussed, Dark Skull was a tremendous triumph, and The Great Movement follows in its steps. Only this time, instead of Italian and German influence, Russo seems to be exploring the possibilities of Soviet montage and social realism, retrofitted as a new cinema for a new world…

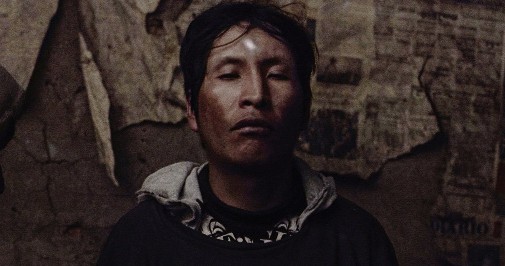

Julio César Ticona stars as Elder once more, though his recent odyssey is an inverse of his past movement. Death once took him from the city to the mining countryside. Now, the fight for worker's rights incites a week-long pilgrimage to the big city of La Paz, whereupon Dark Skull is mentioned as a film where the miners played themselves. Cinema about cinema is a tale as old as time, a mechanism used here to bring the viewer's attention to the form that defines this particular story's telling. In many ways, form is The Great Movement's great purpose, the fountain from which its ultimate meanings emerge.

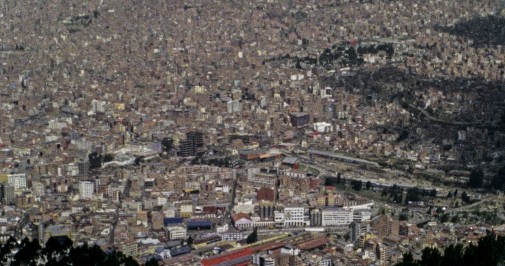

Indeed, before the camera ever glimpses Elder or his story presents itself, the screen lights up with a city symphony. Pondered zooms delineate an eye that looks closer, considering the landscape but wanting to peruse the ant-like humans imperceptible from such a great distance. And yet, it's in the body of its people that a city truly lives - both in fragments and condensed. Elder, we'll come to understand, is something of an anthropomorphized synecdoche for Russo's narrative considerations. His plight is that of the worker, his body Bolivia, and La Paz's pandemonium lost up high in the mountains between beautiful nature.

He's a man, sure, but every man is more than himself. He's also dying, lungs full of dust and rock, accumulated over eternities picking cave walls underground. Not that any doctor seems capable of finding the physical reason for Elder's fragility, either blind by ignorance or blinded by a system that sees workers as expendable. In an Eisenstein-like cut, from the mine of memory to the city market where Elder tries to earn some cash, sweaty machinery gives way to ground meat. As the flesh pulverized into tentacles of red pulp, so is the worker fulminated by cold forces.

Exploitation grounds the body, the mind, and soul, until all that is left is meat sold for meager sums. It's not subtle, but the tradition of Film History to which Russo appeals wasn't known for its subtlety. The reference isn't hidden, mind you, for the director scores the picture's climax to a track taken from Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera. The umbilical cord connecting these films is strong, but the modern creation almost feels more violent than the Soviet agitprop. Maybe the big difference lies in the intention of each project. Though often gazing upon misery, Vertov was shooting an exaltation of hope.

The Great Movement regards hope as a luxury that only a privileged few can enjoy. For the majority, such mercies are out of reach. Instead, the picture is shaped like a cry for change, full of sound and fury, fires blazing within its celluloid heart. Nevertheless, to characterize Russo's film as pure despondence feels wrong. It's not misery porn, by any means, finding paradoxical euphoria in the pits of despair. Oddly revitalizing, The Great Movement appeals to storytelling traditions and kind lies, camaraderie, and hustling fraternity. Though without mercy, Russo's cinema is full of life.

Such powers that verge on transcendence reach their apotheosis by the film's conclusion, an explosive flurry of radical editing that rips itself apart in the process of performing a miracle. On the precipice of the ultimate end, the camera approaches the dying man, discovering light in the shadow before a supernova flashes the entire film before our eyes in accelerated repetition. At the speed of light, maybe the speed of imagination, the picture turns into a cracked mosaic, an unraveling tapestry whose threads are being sucked into a black hole.

Lyricism bursts open from a carcass of dead realism, immersive cinema that finishes itself off with a punch directly to the spectator's face. By the end, I felt pummeled by the magnitude of Russo's vision. Yet, utterly crushed, I yearn for more. After the punishing wonder of Dark Skull and The Great Movement, I can't wait to see what more this director has in store.

The Great Movement, which won a prize in Venice and later represented Bolivia in the Oscars, is enjoying a limited release in the US, distributed by Kimstim Films.