Entries in A Single Man (8)

Curio: Marie Harnett's Pencil Drawings

Tuesday, January 15, 2013 at 10:00AM

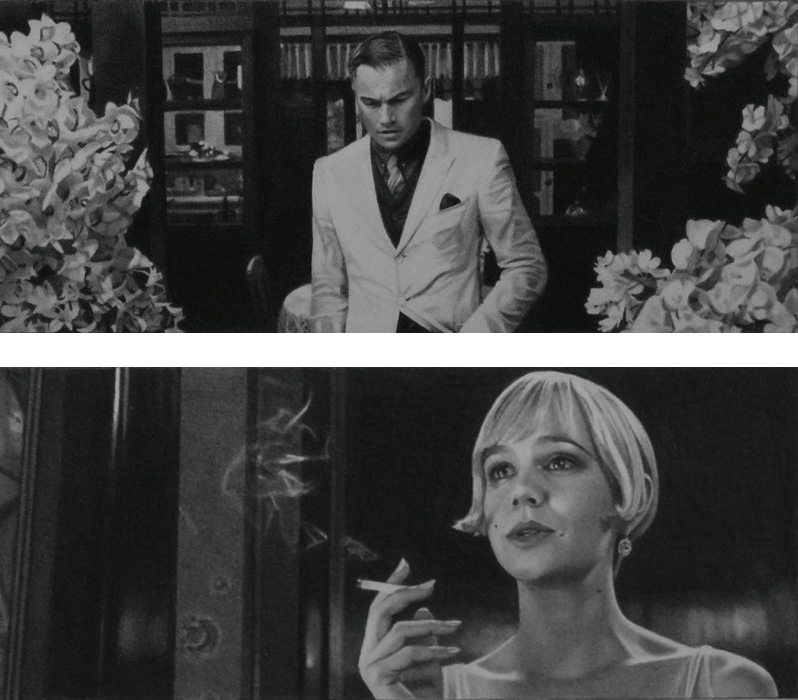

Tuesday, January 15, 2013 at 10:00AM Alexa here with your weekly art inspiration. Marie Harnett is an artist out of the UK whose focus is on film. She makes widescreen-format, small yet intricate pencil drawings of filmstills that "capture fleeting moments of drama, suspense or beauty and, when released from the original context of the film that inspired them, the drawings each tell a story of their own."

Marie holds a miniature Keira

Marie holds a miniature Keira

I recently came upon her work and was struck by the level of photorealistic detail she manages to cram into her tiny compositions, and by how they evoke the history of cinema, despite her of-the-minute subjects (she even draws stills from trailers). And she's doing quite well for herself; tiny mezzotints of her drawings sell for upwards of $2000! Here are some examples of her current work; you can see more on her website.

'Gatsby' series, 2012

'Gatsby' series, 2012

Gangster Squad, Chéri, and A Single Man loveliness after the jump

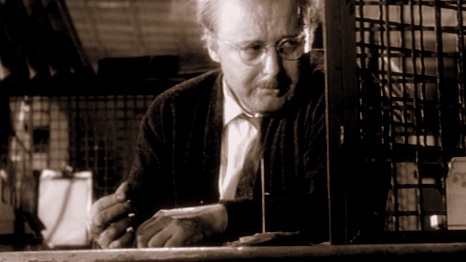

Distant Relatives: The Pawnbroker and A Single Man

Thursday, December 15, 2011 at 3:00PM

Thursday, December 15, 2011 at 3:00PM Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film.

Dead spouses are great dramatic devices. They can give your lead character an extra dose of pain and pathos and add some emotional heft to a bland plot, some sympathy to a distant character, or in the case of a good-old-fashioned revenge movie, incite the action. At its most banal, the dead lover is an obvious cliche. But occasionally it can sweep us up into the protagonist's psyche, force us to ask their same questions about our lives and loves. Those questions, pondered and feared by anyone whose ever been in love: "What if this person died, suddenly, tragically, unexpectedly?" "What if I weren't there to save them, help them, comfort them?" "What if their death were no more to me than a vanishing act. One day here, the next gone... no farewell, no funeral." "What would become of them?" "What would become of me?" These are worst case scenarios to be sure, and we repress the thoughts by telling ourselves that such occurrences are rare (I imagine the exact same thing that anyone whose ever experienced it told themselves too). We watch movies about people who've had such experiences not out of morose voyeurism but out of a desire to understand a state of being that we hope never to be in but realize we easily could.

Our two films today follow men who are mourning the death of a companion and who are, to use a cliched phrase, dead inside themselves. The Pawnbroker tells the story of Holocaust survivor Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger), a man who lost his family and now lives surrounded by the dirt and corruption of New York City. At roughly the same time, on the other end of the continent, George Falconer (Colin Firth) is barely coping with the death of his partner Jim. George, the subject of A Single Man lives among the sunny skies and bright colors of 1960's Los Angeles. The environments of George and Sol, while polar opposites serve the same dramatic purpose, to highlight their state of mind. Sol's is representative. George's is sadly ironic. Added to this is more than a hit of expressionist style, the gritty choppy manic pacing of The Pawnbroker contrasted with the color boosting and desaturated highs and lows of A Single Man.

Both George and Sol have similar supporting characters in their lives. There are two to whom I'd like to draw your attention. They, in turn, represent George and Sol's impossible futures and unattainable pasts. To George, his friend Charlie's (Julianne Moore) propositions of a move back to England and a quaint straight existence are both impossible and offensive. And for Sol, the advances and attempted comforts of a neighborly Social Worker are something he has no intention of dignifying. Both paint pictures of a future that neither man wants to partake in, yet they only serve to emphasize the pain of the present. As for the past, it shows up in the form of two young potential proteges. For George that man is Kenny, a student who is fascinated by him and a bit flirtatious. For Sol it's his shop assistant Jesus, whose desire to learn the business he continually ignores or rebuffs. Both of these young men possess not necessarily much optimism or intelligence but a youthful exuberance, an almost recklessness that neither Sol nor George have present in them anymore. While George engages with Kenny in a way that Sol does not with Jesus, it may be because George has given up on life and planned a suicide while Sol has decided to go on being a living ghost.

Ultimately these films don't have any particularly encouraging messages for the man whose loved and lost. George and Sol float through their existence, flashing back to the moments that have defined them, whether they were present or not. Both men are presented opportunities to feel again, and though they resist and resist, they eventually give in tho their humanness in different but equally tragic ways. For Sol it is a new sadness too deep to ignore, for George a fleeting optimism, quickly snuffed out. Both men are outsiders in worlds that should be embracing them and comforting them, but instead are shunning and fearing them. Both men may have to work too hard to heal. But messages about learning to love again and letting people in aren't the point. The point is to get into the minds of these men and understand what makes them work, how their sorrows manifest, how their lives have become irreparably changed. These films give us insights into the inner workings of men on a precipice none of us ever hope to be. Neither film promises much jubilation but both deliver plenty of humanity.

Other Cinematic Relatives: Veritgo (1958), Last Tango in Paris (1973), About Schmidt (2002), Up (2009)