Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film. This week the first in a three part series on how one classic film can have many children.

After a year that celebrated films about redemption and sentimentality, it's difficult to look at movies about poverty and struggle and not feel like a downer. But there's a reason why a film like The Bicycle Thief, or its neo-realist brethren is considered among the best of all time. Similarly, there's a reason why enough young filmmakers today are inspired to take on that same topic of hardship to make up a small movement that's frequently labeled "neo-neo-realism" (if you're into things being labeled), including Wendy and Lucy. And it has nothing to do with presenting a vision of a world devoid of hope or happiness.

The old joke phrase, "I'm not a pessimist, I'm a realist" doesn't apply here. The purpose of these films isn't to convince you that the world is impossibly sad. So instead, replace the word "realist" in that phrase with "humanist" and consider that the success of these films is based on the fact that their creators truly care for their subjects. How many Hollywood blockbusters that present use with canned happy endings, have no real interest in the actual humanity of their characters?

The Bicycle Thief and Wendy and Lucy present humanist portraits of two troubled souls on a quest to improve their lives and keep their families together. It makes no difference that in one case "family" is traditionally defined and in another it's a girl and her dog. Companionship is companionship as is unconditional love. And in both cases, this singular quest gets sidetracked with familial consequences.

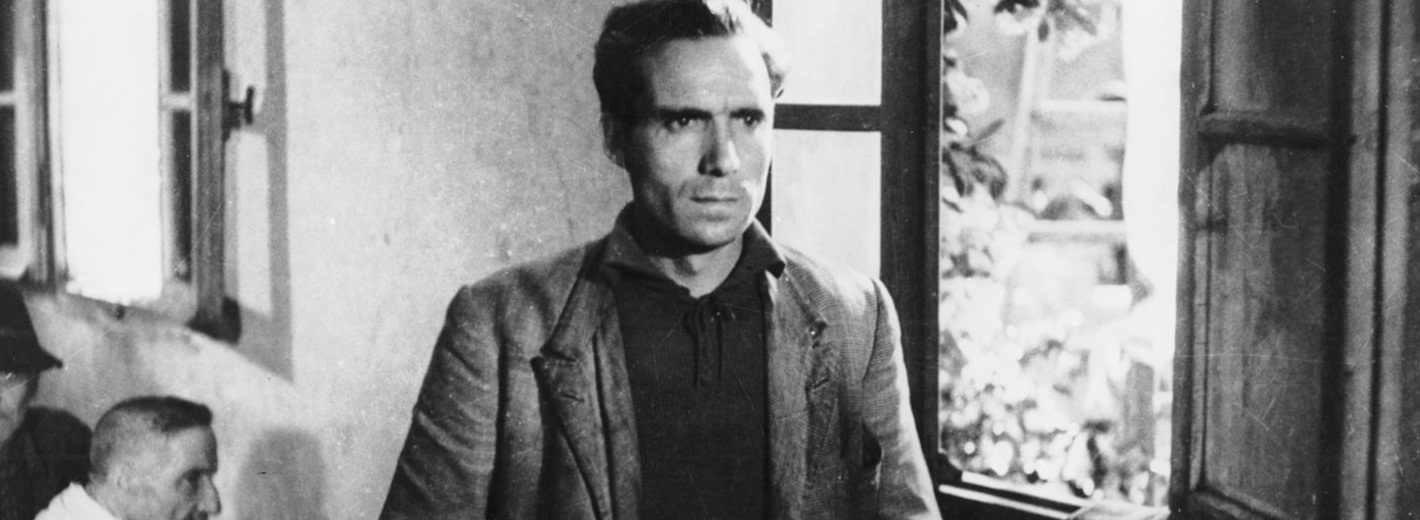

The plot of The Bicycle Thief is well known for both its simplicity and effectiveness. Impoverished Antonio, having just secured a new job that requires a bicycle, has his bicycle stolen out from under him. He wanders through the streets of his village accompanied by his young son, hopelessly attempting to catch the thief and retrieve his bike. Of course, additional things happen, but this is all the viewer needs to know. We may not have all felt this level of desperate, but we can all understand desperation. Similarly Wendy and Lucy can be summarized to easily evoke emotions. A poor young woman, Wendy and her constant companion, her dog Lucy, are on their way to a better life in Alaska. When Wendy is detained by the police, Lucy disappears and she'll spend the rest of the film trying to find her.

The humanism in these films lies in the fact that we care for these characters vicariously through the eyes of their directors, and in doing so understand that there are those who similarly care for and empathize with us in our moments of need. We root for both of these characters even as their missions seem to be leading them toward the same inescapable conclusion.

It's a conclusion as inescapable as their poverty, and it's that understanding that further connects the two films. Why is it so difficult to ascend financially in the world? Because even a small disaster can derail a life. A stolen bicycle, a broken car, a lost dog, can bring an immediate end to a hopeful journey. For the wealthy, minor nuisances are just that - minor, forgettable, easily overcome.

In addition to their own diminishing success in life, Antonio and Wendy have to contend with the fraying bonds of their family, another theme familiar to us all. There is a moment where you realize that your relationship to someone close has been eternally altered and can never go back, and both of these films present these tragic moments as yet another consequence of their noble but unachievable goals.

The Bicycle Thief and Wendy and Lucy succeed by compelling us so easily to root for Antonio and Wendy. We feel their frustrations and successes so completely. To do so both directors utilize a style of simplicity and obtrusiveness. Obviously this is where the "realism" part of their respective movements comes from. But it's unfair to dismiss the obvious, since it contributes so much to these films' brilliance. By intimately placing us next to the action in the role of the all-seeing camera, these films make us a part of the story and give us no choice but to be surrounded by their reality, feeling all of its humanity, and depositing us on the opposite side of tragedy, and in doing so making us feel perhaps the slightest glimmer of hope once again.

Thursday, March 29, 2012 at 3:00PM

Thursday, March 29, 2012 at 3:00PM

Brief Encounter,

Brief Encounter,  David Lean,

David Lean,  Distant Relatives,

Distant Relatives,  Once

Once