Distant Relatives: F for Fake and Exit Through the Gift Shop

Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 4:00PM

Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 4:00PM Robert here, with my series Distant Relatives, where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through a common theme and ask what their similarities and differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema. There's a mixed response on the internet in terms of how much of Exit Through the Gift Shop to reveal. Some people will tell you nothing, some will give you a smattering of plot. I'll do the latter, though I won't give away any secrets (for I know none) but I will discuss some of the mysteries.

F for Film

When Orson Welles made F for Fake in the mid-70's his reputation was somewhere between visionary director of the greatest movie ever (he'd won his honorary Oscar a few years earlier) and washed up, indecisive, expatriate. Far removed from the War of the Worlds episode, it's unclear how many people saw him as the master charlatan he proclaims himself as the host of his film. At the time F for Fake was a strange and new type of documentary. More essay than narrative, Welles himself serves as ringmaster, telling us the stories of famous art forger Elmyr de Hory, fake biographer Clifford Irving, and others. When it premiered it was, predictably shunned by a public who didn't know what to make of it, the other bookend to Welles' cinematic career.

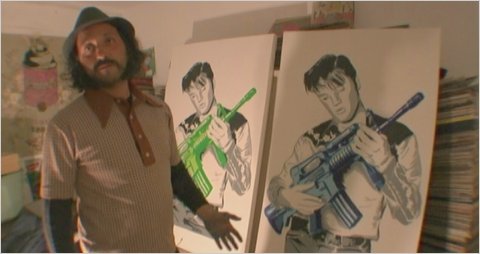

Exit Through the Gift Shop is the first film by Banksy, English street artist, man of mystery whose identity is still unknown and whose work has sold for thousands of dollars thus legitimizing the street art movement and thus doing what to it? The film follows Frenchman Tierry Guetta who uses his ever present camera to chronicle the likes of Banksy and Shepard Fairey before taking up the movement himself to much success, and dismay of his contemporaries. The major debate sparked by the film is whether Mr. Guetta, who does his art under the pseudonym Mr. Brainwash and is never actually shown creating is, in fact, a creation of the film itself, meant to make some larger point about commercialization or populism.

The joke is on us

Elmyr de Hory - fake

Elmyr de Hory - fake

Welles and Banksy are clearly two personalities who enjoy their self-adopted trickster status and relish any opportunity to embellish it. But is the joke on us? Is our deception, our infuriation, part of the point? The idea of passing off something fictional as something true wasn't invented by Welles or Banksy. They join a large collective which includes Michelangelo's early forgeries, P.T. Barnum's famous claims, Vladimir Nabakov's Lolita prologue, Peter Watkins' films, Andy Kaufman, everything Andy Kaufman, Jonathan Swift's misunderstood commentaries, into modern times with Sacha Baron Coen, the Blair Witch Project, or Joaquin Phoenix (though let's not get into that).

Let's talk about Werner Herzog who believes that verite truth is overrated. In his documentaries he often stages moments and feeds lines to his subjects. Why? Because sometimes manufactured reality is more truthful than actual reality. Truth is something both Welles and Banksy are going for through these films which are works of art. This is where questions and realities begin to double back on top on themselves. If art is a fictional representation of the world (even, as Herzog believes, the most untouched documentaries can't achieve objectivity), then what about fictional representations of art?

But is it art?

Thierry Guetta - fake?

Thierry Guetta - fake?

What is art is a question that isn't likely to lead to any consensus, but it is what Welles and Banksy are asking with these movies. If Elmyr and Mr. Brainwash have achieved success through their art (in sales, museums and galleries) then what sets them apart from "real" artists? Perhaps success isn't how we should judge art. Perhaps it should be up to the critic and the expert. But as Oja Kodar, Welles' lover and subject of F for Fake suggests, what purpose serves the experts if they can't deciper the fakes? If the experts disappeared, would the fakes? These films leave us with more questions than answers.

Exit Through the Gift Shop is one of several recent films which have generated a surprising amount of controversey over just how many of their elements are fictional or not (it's hard to generate controversey these days without wading into the pools of political opinion or explicit content). Here perhaps lies the significant difference from F for Fake to Gift Shop. Welles' subject Elmyr was well known as a forger. Clifford Irving was eventually outed as a fraud. Even Welles reveals his hand at the film's finish, quite a ways after it's gone off the tracks. But don't expect Banksy to give us any answers any time soon. Perhaps for him, and for a new generation of charlatan artists, truth need not be revealed as if it's fact. Truth is in the eye of the beholder.

Banksy,

Banksy,  Distant Relatives,

Distant Relatives,  Orson Welles,

Orson Welles,  documentaries

documentaries