Distant Relatives: Raging Bull and The Social Network

Thursday, February 17, 2011 at 11:30AM

Thursday, February 17, 2011 at 11:30AM Robert here, with my series Distant Relatives, where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through theme and ask what their similarities/differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema.

At what price greatness?

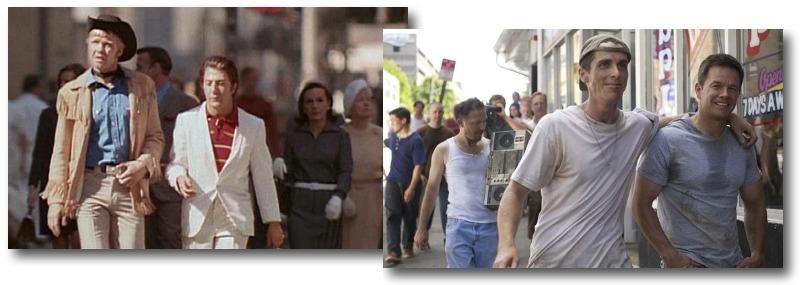

You may think, at first glance, that the 2010 film that has the most in common with 1980’s masterpiece Raging Bull is The Fighter. Yes they’re both about boxing and boxers, but that’s practically where the similarities end. As far as stories about misanthropes striving to do something great while sabotaging their own relationships, few come closer to Jake LaMotta than The Social Network’s Mark Zuckerberg. One immediate similarity is that they’re both real people, but for our sake here we will forget that and approach them simply as characters within their respective movies.

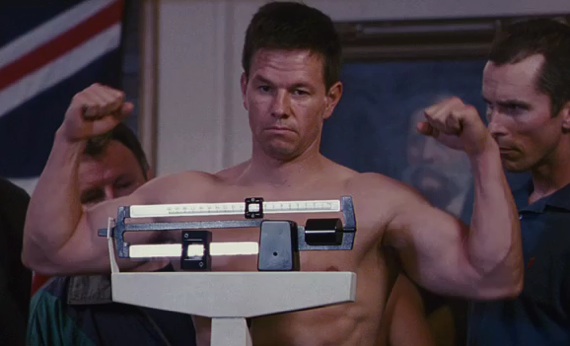

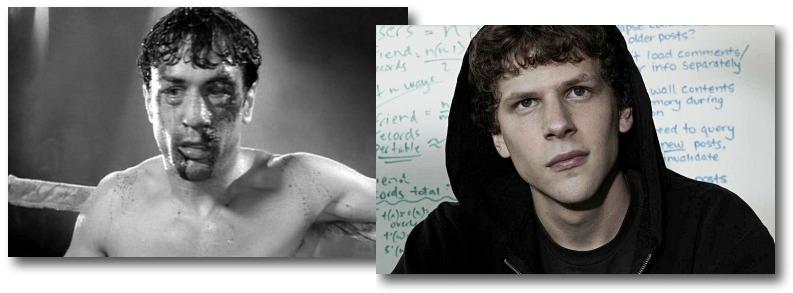

Raging Bull is the story of boxer Jake LaMotta (Robert DeNiro), his relationship with brother Joey (Joe Pesci) and wife Vicki (Cathy Moriarty) over whom his protectiveness manifests itself in more and more aggressive ways as he rises and falls from the grace of the boxing world.

The Social Network is the story of Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) the creation of Facebook, and how the process dissolved his relationship with his best friend and was fueled, in part, by his contempt for rowers Tyler and Cameron Winklefoss (but really everyone).

Did you poke my wife?

We start off with two socially awkward characters though their awkwardness manifests itself in different ways. LaMotta seems unable to do anything without the assistance of his brother, not score matches, not find the favor of women. Zuckerberg meanwhile is very capable, but his non-existant social graces don’t allow him any awareness of anyone in the room but himself. Added to this awkwardness is a good helping of narcissism, though LaMotta might wait until you know him better before aggressively insisting on his own greatness. Zuckerberg would probably tell you up front. And topping all of this is a strong dose of jealousy.

In an odd way, perhaps it's that jealousy that helps buoy both to the top. LaMotta's jealousy manifests itself in the constant suspicion that his wife is sleeping around. The thought of his opponents with his wife certainly doesn’t hurt him (though it does them) in the boxing ring. Would the world championship LaMotta wins be possible without this factor motivating him to throw punches? In the case of Zuckerberg, we can be pretty sure that his disdain for the Winklevii and rowers in general isn’t the only reason he starts Facebook, but notice how he doesn’t commit to (with the intention of stealing?) their project until they reveal that they row crew. In fact the entire quest against crew begins in the film’s opening scene where a casual remark by his soon-to-be ex-girlfriend Erica about liking guys who row crew should be easily dismissed, but Zuckerberg carries it well into the argument, eventually sarcastically spewing “and I’m sorry I don’t own a rowboat.” How much does this anti-crew bias, perhaps a feeling of inadequacy compared to his girlfriends preference of world class Olympic athletes, fuel Zuckerberg? And how much is he fueled by jealousy toward his best friend Eduardo’s impending acceptance into one of Harvard’s Final Clubs?

Eventually it destroys his relationships, another thing he shares with Jake LaMotta. LaMotta’s raging jealousy destroys his ties with his brother and his wife. The self-centeredness that pushes both of these men toward greatness also burdens them with a set of blinders, unable to care for their relationships with the people they care for.

Cracking some eggs

There is another tie here. Boxing and cyber enterepeneurship may be vastly different professions but they’re professions that neither LaMotta nor Zuckerberg can separate from their personal lives. LaMotta punches people for a living. It’s what he knows. And so at home, he can only express himself by punching people. Zuckerberg is a little more complicated but the connection is still present. In creating Facebook, Zuckerberg has invented a reality where the intimacy of friendship is a secondary thought and “friends” are treated more like an audience for one’s self-promotion. So it goes in Zuckerberg’s life. He’s less interested in mature relationships with actual friends than being surrounded by individuals who are in perpetual awe of his greatness.

Much like our discussion of Charles Kane and Daniel Plainview earier, the differences between these two men are found in the consequences or perceived consequences of their actions. LaMotta gets it worse, losing his title, becoming a fat joke, jailtime. Yet at the very end, we can’t know how triumphant he is in his own mind. When he says “I’m the boss, I’m the boss, I’m the boss,” is he just trying to convince himself? When Zuckerberg declares “I'm the CEO... bitch” he may also be trying to convince himself of his own greatness, but he pays a far lesser price for his self-superiority. Lawsuits sure, a drop in the bucket (he doesn’t care about money) and the loss of his friends like LaMotta, but no jailtime, no scandalous encoutners with underage girls like LaMotta (that’s for another member of the Facebook team.)

As an audience we love tales of the rise to and fall from glory, a little abnormal psychology to remind us that greatness requires sacrifices too great (and of too many values) not to appreciate the mundanity of our lives. But why sets the modern film apart is how many people may in fact noting trading places with Zuckerberg, the world's youngest billionaire. Truth is, The Social Network is not a tale of rise and fall but just a tale of rise (with consequences of course). As an audience perhaps we no longer expect the fall or demand the fall or realize since the true story of Mr. Zuckerberg is still ongoing there may very well not be one.

In both cases, LaMotta and Zuckerberg, we can look at the success and ask according to our own standards "was it worth it?" In the twenty years between these films it may not have become easy to answer "yes" but it's gotten easier.