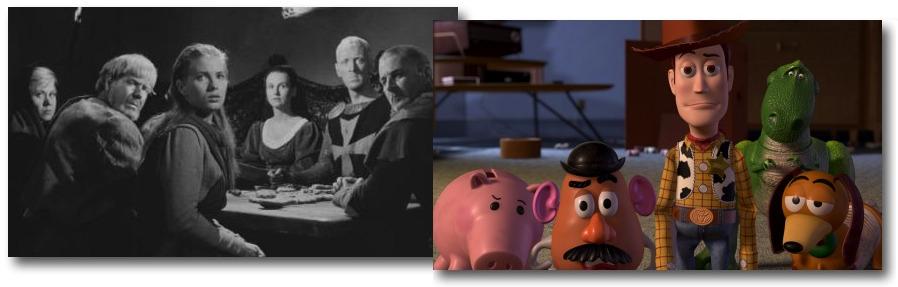

Distant Relatives: The Toy Story Trilogy and The Films of Ingmar Bergman

Thursday, April 7, 2011 at 6:30PM

Thursday, April 7, 2011 at 6:30PM Robert here, closing out the first season of my series Distant Relatives, (where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through theme and ask what their similarities/differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema) with a two part special.

The meaning of life

It may seem like a cheat to compare a trilogy of films to a director’s entire collected works. Surely it wouldn’t be that hard to find elements in anyone’s filmography that happen to match up to the Toy Story films which cover a wide array of human (er, toy) emotion. But it’s not just random or occasional moments or themes that we’re talking about. When I see the Toy Story films, I see a primary emphasis on the two concepts that Ingmar Bergman explored though his entire career: the quest for meaning in life and the sorrow of being parted from those we love (one might also say the silence of God is in there but I find it to me more of an offshoot of those two motifs, more on that later). Indeed if Ingmar Bergman were a modern animator the Toy Story films may very well be what his output would look like.

But let’s talk about quests for meaning and the importance of relationships in today’s animated films. These are ubiquitous themes. The heroes of films like WALL-E, Shrek, The Incredibles, Ratatouille, How to Train Your Dragon, Up all find themselves on a quest that will bring a new sense of purpose to their rather humdrum lives. In the process they make a new connection or rekindle an old connection with a friend, spouse, family member, etc. The relationship helps them complete their quest, and the quest reinforces the relationship, all together bringing a new sense of meaning to all involved.

So what makes Toy Story special? Two things. First, in the Toy Story films, all three, the quest isn’t reinforced by coming together, the quest is coming together. No one is trying to save the world, rescue a princess, defeat a villian, cook a meal, quell a dragon, or protect a giant bird. No one is trying to assign new meaning to their lives. They’re simply trying to hold on to their current meaning by coming together (consider the quest of the characters in The Seventh Seal to simply return home, or the children in Fanny and Alexander to rejoin their family). Secondly, without grand designs, the characters of Toy Story tend to ask heavier questions. The kind you’d find in an Ingmar Bergman film, like “what is my purpose here?” “am I fulfilling it?” “what would it become if the being whose love gives me meaning ceased loving me?”

When somebody loves you, everything is beautiful...

In Bergman’s films this “being whose love gives meaning” takes on two forms. The first is God whose presence characters like The Seventh Seal’s Antonius Block or Tomas, the preacher from Winter Light search desperately for, hoping that it will lead them to some sense of light. The second is a spouse or partner. Bergman, who was married five times, made several films including Scene From a Marriage and Shame (as well as writing the great Liv Ullman film Faithless) about the dissolution of a marriage and the meaninglessness into which both parties are subsequently thrown.

The role of god/partner is filled in the Toy Story films by the toys’ owners. No, Andy is not a god, but he is a higher being. he owns the toys. They live in a world of his creation. While the toys don’t exactly worship Andy, they do occasionally suggest that they should accept his will for their being, such as Woody’s insistence that they resign themselves to the fate of the attic. But Andy and the other kids don’t require any faith in their existence. They’re flesh and blood. And in this way they fulfill a somewhat spousal role, not in a romantic sense, but in that they encompass the great love that the toys hope to find in life, and once found, they consider themselves fulfilled (or at least should be). But there is another dynamic going on here. As quasi-owner, playmate, and provider of love, kids will see a very parental relationship between Andy and his toys. However, although the toys get autonomy between playtimes, there is no eventual emancipation. Quite the contrary, it’s the owners who eventually move on leaving the toys as empty nesters. Imagine that, all the love you desire from parent, partner, and god pent up in the impulsiveness of a child.

Parting is such unendurable sorrow

Which is why the characters of Toy Story live in constant fear that it could all end tomorrow. And if it does, what does that say about the meaningfulness of the entire experience? There is, in the world of Ingmar Bergman and in the world of Toy Story, no greater sorrow than the separation from a loved one. When Jessie the Cowgirl is discarded by Emily or Lotso by Daisy it’s enough to throw someone into a state of perpetual sadness or evil, like the unfeeling sisters of Cries and Whispers. When Woody sees the newer better looking Buzz Lightyear arrive, he fears for the outcome experienced by Scenes from a Marriage’s Marianne (played by Liv Ullman). Replaced by a younger model. Through no fault of your own. You just aged. You just were. And it was not good enough.

Even worse is the possibility that what you always perceived as love was in fact ambivalence. That the presence of chaos and meaninglessness is your fate. In Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly, Harriet Andersson’s Karin has a mad vision of a spider god, a Deity not of love but baseness, staring at her with if not uncaring, utter contempt. There is no god to provide you with love. God is a spider. God is Sid. The presence of a character like Sid in Toy Story is the (shocking for a child’s movie) recognition that chaos and darkness exist. That just as easily, yoy could have been Sid’s toy. Like the mysterious perpetrator who goes around mutilating animals in Bergman's (underseen but great) The Passion of Anna, Sid mutilates his toys with no real purpose but his perverse pleasure. And to witness those mutant toys is like Max von Sydow witnessing his “mutant” neighbors in Hour of the Wolf. It’s the realization that you are in the presence of a truly evil creator. Life loses meaning. Chaos reigns.

CONTINUE TO PART TWO How does one regain meaning in a world like this: By assuming power? By taking a place of honor in a museum? By defeating the evil Emperor Zurg? Travel to heaven and hell and back.

Reader Comments (4)

This is beautiful... thank you. I always try to find the real connection that Bergman Films have in my life, and it's refreshing to view them as universal truths and how best to compare them with something that people see as light fare, like an animated film.

This was so beautiful and sad and meaningful. I look forward to part 2.

Great Article!

I too share the same feelings, Bergman touches on topics like religion, philosophy, metaphysics and also talks about modern materialistic aspects that are affecting the humane nature. Pixar too with awesome animation, larger than life characters, stimulating plots and with outstanding storytelling, every movie of theirs artistically expresses hope and respect for the positive values of life.

The Toy Story franchise is among Disney / Pixars' most successful franchise. It's appeal is universal as both kids and adults can really understand the toy and toy stores' life. More importantly, it also tells a lesson about life.