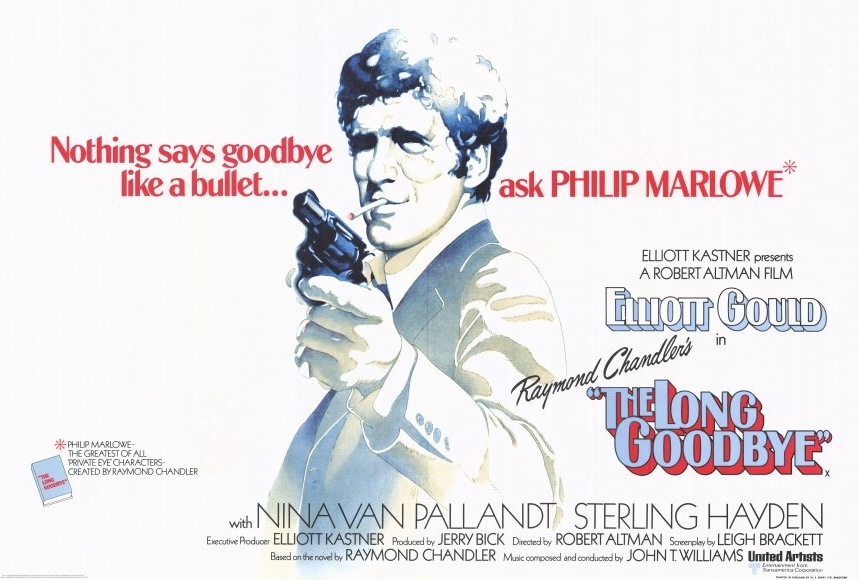

1973 Look Back: Robert Altman's "The Long Goodbye"

Tuesday, July 22, 2014 at 1:16PM

Tuesday, July 22, 2014 at 1:16PM We're giving 1973 some context as we approach the Smackdown. Here's Matthew Eng on an Altman film.

There’s an unmistakable sense of nostalgia that permeates Robert Altman’s seldom-seen 1973 neo-noir The Long Goodbye, an air of reminiscence highlighted by the film’s title track, a nifty, pliable, lovelorn little number composed by John Williams and Johnny Mercer that gets incorporated endlessly throughout the movie, evoking sporadic familiarity, even though we rarely hear the same version twice. It transforms itself, from scene-to-scene, into a flimsy piece of supermarket Muzak, an ivory-tickled barroom ditty, even a castanet-laden flamenco. It’s a caressing torch ballad one moment and a marching band’s funeral hymn the next. The song, in all its reimagined incarnations, continually threatens to embed itself into the viewer’s mind, but just as quickly eludes any tighter hold. It’s as though the film, in its own increasingly weary, tumbledown sort of way, is nostalgic for the tune, longing for something that comes back but is never the same.

It’s telling of Altman’s intentions that the film forsakes any other discernible music apart from this titular track, save for the classic, semi-satiric “Hooray for Hollywood,” which opens and closes the film. The Long Goodbye may be based on an eponymous Raymond Chandler novel, centered around a character made legendary by Bogart, and hitched to an entire history of early noir filmmaking, but it is not a mere, Body Heat-like retread. And although there may be obvious admiration and even some slight affection for the genre in all of its former, mannered glory, it’s certainly not a love letter.

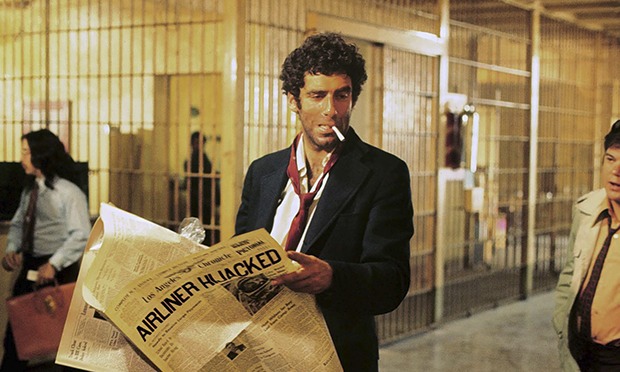

Altman structures the film with a looseness that is perfectly in keeping with his particular directorial eye but that also succeeds in dismantling the stylized tightness with which most noir is crafted. By choosing not only to utilize natural lighting in Vilmos Zsigmond’s richly muted cinematography, but to also set a great deal of the film amidst the sun and sheen of daytime Los Angeles—in addition to the inevitably inky nighttime skies and murky, threadbare apartments—Altman releases and relaxes his film, creating a tonal ease that places it in direct contrast to the endlessly unnerving tautness of most noir. He again allows character details to reveal themselves in the freewheeling interplay that typify the unusual anecdotes of an Altman landscape, if not necessarily a noir one. He is still interested, as ever, in letting us casually intuit character from behaviors and reactions, rather than clinically hear about it through blatant exposition, especially when it comes to his own flamboyantly-reconceived protagonist.There would be no Long Goodbye without Phillip Marlowe, the private eye that Bogie burned into celluloid in 1946’s The Big Sleep, which was itself co-written by Goodbye scribe Leigh Brackett. Bogart-as-Marlowe is a character-typeso powerfully impressed into the moviegoing public’s collective memory that the only sensible thing to do in this rethinking would be to completely turn the character on its head, which is why the casting of Elliott Gould as Marlowe is key, since Gould, the ultimate Hollywood Supermensch, is all but the antithesis of Bogart’s hard-boiled grit. Given new embodiment by a gangly, curly-haired, smirk-faced comedian, Marlowe becomes a character who eschews any straightforward definition. All the basic, enduring elements of Marlowe’s character are purposely made present in the film, from the black suits and the chain-smoking to the sly wisecracks and the deadpan delivery of said cracks. But rather than merely alluding to these attributes, Altman underlines them, calling our attention tothem in order to comment on them. Altman and Brackett use Bogart’s Marlowe as a starting point from which their leading man is then given free will to fashion a totally and indelibly different type of gumshoe. Gould’s Marlowe owns the black suit but is in definite need of an iron, and his smoking is made laughably mechanical throughout the movie, during which Gould can be found lighting up within nearly every single frame. Marlowe still wisecracks aplenty here, and yet Gould’s mumbling, almost farcical deadpan is not the dryly-contemptuous voice of Bogart’s. In fact, the only things they do share are a job description and a carefully-calibrated code of honor.

The Phillip Marlowe of The Long Goodbye is an anachronism, a man obviously out of place in the sun-soaked, seventies-era California environ he inhabits, but who wouldn’t appear quite at home in the dark and dour milieu of forties-era noir either. He seems stuck in some weird middle ground, trapped in a time to which he doesn’t belong and clamoring for one that he has no place in either, a pretty apt description for the film itself.

In Goodbye, Marlowe is tasked with finding the missing husband of a Malibu housewife, while also dealing with the aftermath of his close friend (and accused wife-killer) Terry Lennox’s suicide. Things naturally, comically grow difficult when the debris of the latter begins to wash into his current case. Altman has of course crowded his film with curio members of his stock company, each putting updated spins on classic noir archetypes, including Nina van Pallandt’s sun-kissed, flaxen-haired housewife (more Beach Goddess than Femme Fatale), Sterling Hayden’s boorish, Hemingway-aping hubby, Mark Rydell’s slickly demented kingpin, Ken Sansom’s versatile celebrity impersonator-cum-gatekeeper, and another of Henry Gibson’s powerlessly pint-sized authority figures. There’s also a ridiculous Arnold Schwarzenegger cameo as (what else?) a muscle-bound bodyguard, not to mention one whip-smart, cute-as-a-button, ginger-furred kitty.

Amidst all the comic befuddlement and tricksy reversals, Altman presents us with a sudden, movie-changing act of senseless violence against a background female character, appalling us and Marlowe, while simultaneously dismantling the occasional indifference of filmic violence, especially that which was made so common in noir. There is, of course, an understatedness to the way in which violence is used in Code-created noirs like Double Indemnityand The Maltese Falcon that is artfully effective, and yet Altman importantly suggest that there might also be an irresponsibility, perhaps an easiness in allowing these act to go unseen, and further unpunished. There’s a subtle commentary, further emphasized by the alluded pattern of domestic violence that exists in several characters’ households, on the mistreatment of women in film noir, used more often than not as punching bags to be knocked around by Cagney, when not employed as two-faced, trixie sex objects. It’s important then that the female victim of the film’s most harrowing moment of violence remains nameless but not faceless, so that when we see her later, post-incident, the effect is all the more unsettling and more indicative of a deeper ill.

Altman will later end his film with a cold-blooded betrayal of one character’s moral compass, set to the glittering, big-band melody of the classic number that started the film, rousing the culprit to break into spontaneous dance and engage a random passerby to join in, a crime scene sitting not too far away. It’s a shameless bit of meta-commentary, one final, deceptively joyous grace note to a code-breaking picture that has so vividly criticized but also somehow celebrated the undying industry that allows such completely unique cinematic experiences as this to exist in the first place. So “Hooray for Hollywood” maybe, but hallelujah for Robert Altman for always seeming to know what he owed this town but refusing to kowtow to it all the same. For boldly, erratically re-envisioning one of its most revered genres with equal parts respect and recalcitrance, artifice and authenticity. For refusing to iron out the wrinkles in Phillip Marlowe’s suit.

Reader Comments (7)

Wonderful piece. This might be my favorite Altman and your commentary does a lot to point out why.

Plus, as a cat owner, those scenes at the beginning kill me.

Probably my favourite adaptation and definitely my favourite Altman.

I feel like Altman and Brackett and Gould just got it, they got the spirit of it. Everything I like about the book is there- the colourful characters and the asides and the interior design and Los Angeles and Marlowe. There were able to pick him up, drop him in the seventies, have him end it like that and it felt true. Would that more adaptations could be unfaithful with as much aplomb.

(And speaking of gangly comedians I think Cary Grant was Chandler's choice to play Marlowe- would have liked to have seen that!)

SVG: If Cary Grant was Chandler's choice to play Marlowe, would this be as close as we can get to the author's idea of the character?

Volvagia: hmmm... I don't know.

I mean Cary Grant is Cary Grant and Elliott Gould is Elliott Gould. I do think Chandler was quite happy with Bogart's Marlowe (how could you not be happy with The Big Sleep?) -- even though he was a bit short!

I miss Elliot Gould. What a unique presence in the movies.

Altman gets his share of praise for his work, but I've never understood why this film isn't mentioned more often. Brilliant … and most entertaining.

I stumbled across your review whilst lamenting this film's imminent removal from Netflix. Gould's Marlow makes me long for more of this interpretation of the character. Perhaps it's best that was never attempted, but I feel like these's a big hole where a great franchise could have existed.

Is there a problem with the distribution rights to this great film ?

I have not seen it on tv for at least twenty years !