The Furniture: Brazil's Pungent Pot of Duct Soup

Monday, September 4, 2017 at 11:42AM

Monday, September 4, 2017 at 11:42AM "The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Hi there! I want to talk to you about ducts.

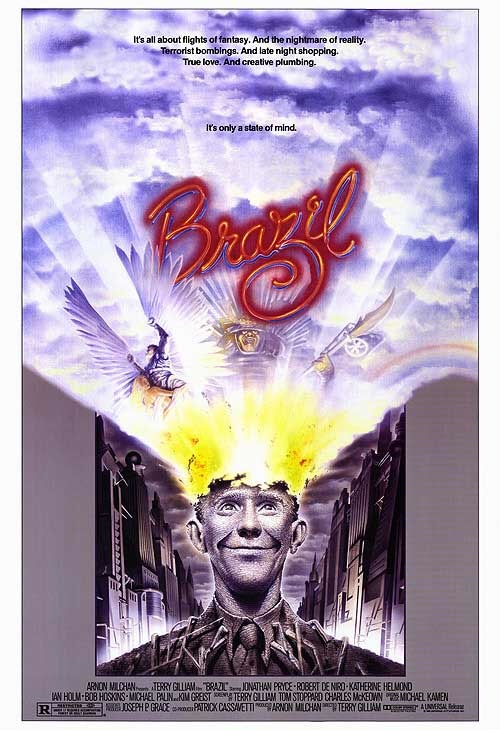

I mean that quite seriously, though I’m also quoting the opening lines of Terry Gilliam’s wacky and wonderful Brazil. It’s a film with a lot of unique production design, for which art director Norman Garwood and set decorator Maggie Gray received an Oscar nomination. They lost to Out of Africa, but I find it helpful to pretend that didn’t happen.

It’s nearly impossible to choose a single element to feature. I’ve half a mind to simply post all of the bleakly hilarious propaganda posters that clutter the walls of the film’s dystopian metropolis. Another option would be the design of the dream sequences, which become increasingly majestic as Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) loses touch with reality.

But I still want to talk to you about ducts...

They’re the tubing that holds the film together, after all. No one ever fully explains what they’re for, but that hardly matters. Not that it matters. They’re the basic visual material of this totalitarian fantasy, even more so than the nightmarish art deco iconography of Central Services.

Lowry is a low-level bureaucrat in this miserable machine, though his well-connected mother is constantly pushing him toward a promotion. His destiny begins to change when he finds himself in the fallout of a clerical error, one that caused the death of an innocent man.

But this is hardly the rare error of a meticulously organized bureaucratic system. The shabby, over-structured Central Services is a disaster, easily jammed and constantly patching up its own mistakes. A single jam at headquarters can send an entire department into hysterics.

Yet, despite this incompetence, Central Service has gotten its ducts into just about every room. We first see them on television, the subject of an old-timey propaganda message.

Then they appear in the Shangri La apartments, where the unfortunate Buttle family resides.

But they are not only in the outskirts and the slums. Lowry’s mother also has enormous ducts in her grand apartment, a fortress of wallpaper and manic decor.

Other ducts lurk behind panels, waiting for the right moment to invade invade. Lowry gets on the wrong side of some Central Services heating repairmen and ends up with a total shambles.

Later it gets even worse, when the repairmen return to kickstart the air conditioning system.

Central Services is vindictive and small-minded. Its authority manifests in the exasperation of its citizens and the constant panic at its headquarters. Its public face is a shabby lie, cheery posters next to sputtering refineries. This is perhaps never more obvious than at the high-end restaurant where Lowry meets his mother. Its interior water feature is fed by enormous ducts.

The food comes in piles of mush, accompanied by a pleasant photograph of what it’s supposed to be. The waiter insists that Lowry order by number, upholding the system of pointless regulation.

But if Central Services insists that it’s duck à l’orange, does that make it duck à l’orange? If Central Services punctuates the streets with red disposal tubes, does that make the city a tidy place?

Eventually the ducts escalate into a final pile, up which a delirious Lowry scrambles. In the tangled mess are other symbols of the regime, a neon blue cross and the scattered wrecks of a few television/computers. The ducts have reached their final form, a filthy mountain of totalitarian garbage.

But before leaving the ducts, one last thought. Brazil doesn’t exist in a vacuum (or an HVAC). It uses fantastical design elements to condense urban space and funnel it into labyrinthine dystopia without end, an approach that has turned out to be pretty influential. Tim Burton’s Batman is a direct descendant, certainly, and one can see similar strategies in The Hudsucker Proxy and the work of Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

These films simultaneously tower over the audience and trap them in an ever-descending elevator to hell. It’s as if the sets of German Expressionism were shot and edited into a nihilist film noir. Incomprehensibly large society collapses upon the head of the impossibly small everyman. But the difference is that Brazil goes a bit farther than the rest, ending at the very bottom of this maniacal cinematic spiral.

Reader Comments (2)

One of the best films ever made.

References allow you to track sources for this article, as well as articles that were written in response to this article.