Michael O'Connor and the costumes of “Ammonite”

Thursday, December 10, 2020 at 7:00PM

Thursday, December 10, 2020 at 7:00PM

As L. P. Hartley famously wrote, "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." When looking back at times gone by, filmmakers often find themselves as the intermediates between the audience and that strange land. Most try, in some regard, to be interpreters, translating foreign tongues to recognizable idioms, adapting what came before to contemporary sensibilities.

Others, like Michael O'Connor are more pedagogue than translator. In his work the oddities of the past are shown naked, and it's the audience that learns how to comprehend a new language. The British costume designer has made a name for himself with great feats of period couture. While purposefully austere, the Victorian wardrobe of Francis Lee's Ammonite is one of O'Connor's best creations yet…

Georgian wedding finery in "The Duchess".

Georgian wedding finery in "The Duchess".

Like many cineastes, London-born Michael O'Connor started his career as an assistant to other professionals in the industry. His collaboration with Lindy Hemming was particularly fruitful and she has credited him with helping her in finding the look of the Harry Potter saga, a mix of the fantasy iconography Judianna Makovsky devised for the first film with inklings of Victorian wear and 1940s aesthetics. O'Connor's first credited work as sole costume designer of a motion picture came in 2001 with Ismail Merchant's The Mystic Masseur. Still, his big break would come seven years later.

In 2008, O'Connor clothed two lavish period pieces. First, there was the 1930s-set comedy Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, where Frances McDormand and Amy Adams galivanted across London in glamorous attire, and Shirley Henderson appears as a lingerie designer. While fun, that picture didn't earn O'Connor many gold plaudits, unlike The Duchess, which found him creating one of the most historically accurate 18th-century wardrobes this side of Dangerous Liaisons. Better yet, the designer didn't need to sacrifice characterization or visual storytelling for verisimilitude. He rightfully won an Oscar for the achievement.

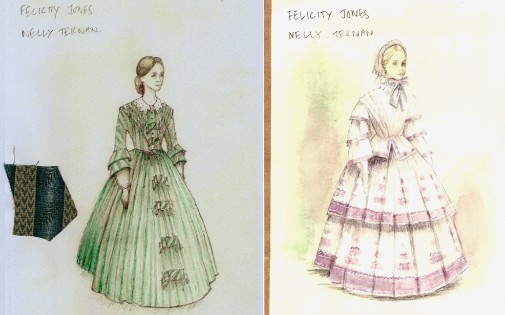

Costume sketches from "The Invisible Woman".

Costume sketches from "The Invisible Woman".

Since then, O'Connor has become one of those names that regularly pop up in the credits of impressively attired costume dramas. Oscar-wise, he's earned two other nods for 2011's Jane Eyre and 2013's The Invisible Woman. His work is consistently great, but it rarely calls attention to itself, on the verge of drabness, unless the particularities of a setting demand overt opulence. He's also unafraid of alienating his audience with historical oddities. Just see his tremendous reproductions of early 17th century Dutch fashions in the otherwise unremarkable Tulip Fever or the Jacobean stylings of All Is True.

In this annus horribilis, O'Connor has brought us another exquisite work of period costuming in Ammonite. The film, mainly set in 1840s' Lyme Regis, concerns the harsh existence of real-life paleontologist Mary Anning and geologist Charlotte Murchison, played by Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan respectively. While the narrative is structured by their budding relationship, it feels wrong to categorize Ammonite as a romance. It's much closer to a double-edged character study where each woman finds solace in the company of the other, a brief respite from anti-social loneliness. That doesn't necessarily mean their on-screen lives are defined by amorous unraveling. As it happens, they aren't.

That is an important differentiation to have into account when looking at the picture's craft. Shot with severity by Stéphane Fontaine, Ammonite is attuned, almost insularly, to its character's internal struggles, their perspective, and personal hang-ups. It's not that the emotion of Mary and Charlotte overwhelms the film, but that their, not entirely voluntary, refusal to express feelings shapes the look and sound of their tale. The sea, for instance, is a constant presence, more so than human company, and its sound often overwhelms even the loudest shouts. Humanity is muffled by the crashing waters.

Immersion seems to be the point of such a construction. That and an invitation for careful observational exercises by which the audience gradually learns the world of the characters rather than having it explained to them forthrightly. O'Connor's costumes thus avoid easy stylization, turning their backs on modern taste and embracing the idiosyncrasies of Victorian garments, these particular women, their class, their struggles. One of the first details we note about Winslet's Mary is that she wears men's breeches underneath her skirts when going out in search of fossils. It's a practical decision, as is her use of an old masculine tailcoat with the back sliced open, but it tells us a lot about her and the society she lives in. After all, the breeches are hidden, always.

Back inside, working at the shop that allows Mary and her mother to make a living, her costume changes to an old démodé dress. It's about a decade out of style and broken down by repeated wear, stained by sweat, faded from the fustigation of salty winds. Her mother, on the other hand, is covered in linens and rough cotton, a bonnet modestly covering her hair, the sign of a married woman in an environment where gender roles are as unchanging as the fossilized ammonites of the title. These are clothes of the dispossessed, of those hanging on to creature comforts by a thread and trying to fight off both the cold and the stares of judgmental neighbors.

When Charlotte bursts into Mary's life, she's a disruptive presence, a mountain of up-to-date fashions in black silk crepe. She's in mourning, deeply so, but her stark attire still reveals how distant her urbanite wealth is from the Mannings' meager living. There's more to her costumes than fashionable grief, though. O'Connor picks up peculiar period details like the centuries-old practice of having detachable sleeves and even different sets of matching bodices to make different outfits out of the same expensive skirt. Charlotte may be married to a wealthy man, but she's not aristocracy. Her clothes reflect the relative frugality of a well-to-do member of the bourgeoisie.

SPOILERS AHEAD

As the two women fall into each other's grace, into each other's beds, their attire subtly evolves. Mary takes out an old dress and adds a removable lace-collar to make it party-appropriate. Charlotte suddenly abandons mourning clothes for patterned outfits whose cotton prints look like corals. The sea again shows its influence, the two protagonists dressed like extensions of the landscape. Red is virtually inexistent in anyone's clothes, its ruby flame reserved for heated flesh in the throes of sex, for intimate passions instead of public decorum.

But, like the sea, every movement forward is followed by a retreat. A wave crashes and then runs from the shore, back to the open waters. Charlotte goes back to her place of comfort, London, and wishes to bring Mary with her, away from the shore, from the sea, the fossils. The violation is noted by a burst of scarlet, velvet bows that tie Charlotte to her city home but put her in glaring discordance with Mary. The color palette has been broken, so has their shared dream of temporary joy. Notice that Mary's closest visual pair is Charlotte's maid who, despite wearing clothes as out of style as Mary's, is still dressed with all the proper accouterments.

The scientist, however, stands in a limp skirt, petticoats left behind in favor of a hidden pair of breeches, the spiral design of her hat an umbilical cord tying back to her home, reminding us she doesn't belong in lacey London parlors. She belongs close to the sea and its spiral fossils, its enticing ammonites. It's characterization through costuming but also a narrative that runs parallel to the text. Matters of class aren't too explicit in Lee's screenplay, but they are unavoidable in O'Connor's costumes. The same can be said about suffocating gender norms that are thus observed, not garrulously explained. It's a film and a wardrobe that demand close inspection, patience, attention.

Ammonite is now available to rent from most services. Are you a fan of its costumes?

Related Post:

Michael O'Connor Interview from 2014

Reader Comments (4)

Great piece, thanks Claudio. I thought the costumes were stunning, as with the rest of the visuals (and Kate Winslet's performance, of course).

Charlotte goes back to her place of comfort, London, and wishes to bring Mary with her, away from the shore, from the sea, the fossils.

This is the first article that has made me want to this film. Great piece, you provided so much depth.

I forgot the existence of The Duchess (which is weird because I am a big fan of Keira Knightley, especially when she is wearing period costumes). But I remember his good work in Jane Eyre, and considering these gorgeous screen caps (and the richness of your analysis) I believe he’s up for a second Oscar.