Hou Hsiao-Hsien @ 75: International Acclaim (1987-1998)

Monday, April 11, 2022 at 9:00PM

Monday, April 11, 2022 at 9:00PM

In contrast with their critical acclaim abroad, the Taiwanese reception of Hou Hsiai-Hsien's films was less enthusiastic. Dwindling box-office returns and accusations that his films were too uncommerciable led the director to attempt bridging the popular and the artful. 1987's Daughter of the Nile returns to the realm of modern Taiwan's youth, abandoning the midcentury narratives that had characterized the autobiographical films. It's also notable for its more significant urban setting and single-minded focus on a female protagonist.

After this project, he wouldn't pay much attention to commercial appeal while his ambitions grew. At the end of the 80s, we encounter a peak of international recognition, the ascension of Hou Hsiao-Hsien to the pantheon of modern-day masters of cinema. All it took was a landmark film that, in 1989, earned the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and kickstarted a trilogy of historical reflections…

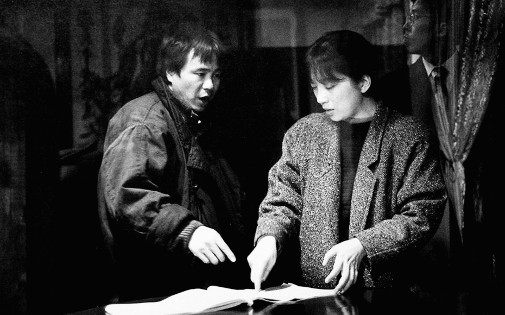

DAUGHTER OF THE NILE (1987)

DAUGHTER OF THE NILE (1987)

To grasp the greatness of A City of Sadness, one must have a basic knowledge of 20th century Taiwan history, how the film fits into a complex cultural context, and its director's feelings about national identity. As detailed in 1985's A Time to Live, A Time to Die, Hou Hsiao-Hsien was born in Mainland China around 1947, when internal conflicts had split the nation between the Mao Zedong communists and the Kuomintang or KMT, the nationalist party led by Chiang Kai-Shek. By 1949, the Communists had proven victorious, with Mao baptizing the country as the People's Republic of China. Fearing political persecution, the KMT fled to Taiwan.

Hou Hsiao-Hsien's family was part of this mass migration that, once again, threatened Taiwanese natives. The island had been under Japanese control until 1945, and the KMT invasion was, in many ways, a new colonialist force. Indeed, the mainlanders formed an exiled government maintained by military oppression. Through it all, people like the director's family held close to their Chinese identity, regarding Taiwan as a temporary home – in the 1985 film, their home's bamboo furniture is a constant reminder of such aspirations. This delusionary hope extended to the younger generations.

Hou Hsiao-Hsien has often characterized himself as Chinese rather than Taiwanese and even briefly supported a party in favor of Chinese reunification. However, his films have confronted intrinsically Taiwanese matters, including a question of national identity informed by a history of colonialist rule and violent subjugation. In 1987, when the martial law started by the KMT came to an end, the director started what was to be the first public acknowledgment of such taboo events as the party's purges which resulted in tens of thousands of lives lost.

A CITY OF SADNESS (1989)A City of Sadness was to be an exercise in unearthing censored history that had only survived through oral tradition, the witnesses hushed words. However, in a gesture of profound humanism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien kept his focus microscopic, anecdotal, private. Despite its grandiose scope, detailing the events of 1947 through 1949, the film portrays a family saga, each individual's story an irreplaceable thread in this cinematic tapestry. Between the Japanese withdrawal and Taiwan's secession from mainland China, the Lin Family suffers immense loss, life and death forever tangled.

A CITY OF SADNESS (1989)A City of Sadness was to be an exercise in unearthing censored history that had only survived through oral tradition, the witnesses hushed words. However, in a gesture of profound humanism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien kept his focus microscopic, anecdotal, private. Despite its grandiose scope, detailing the events of 1947 through 1949, the film portrays a family saga, each individual's story an irreplaceable thread in this cinematic tapestry. Between the Japanese withdrawal and Taiwan's secession from mainland China, the Lin Family suffers immense loss, life and death forever tangled.

Their narrative is a sorrowful elegy about displaced people, their film an observation of fragile serenity in the face of chaos. The adult Lin brothers take center stage in this melancholic study, each a symbolic entity and a multidimensional character. There's the eldest, a business owner whose livelihood is threatened by political upheavals. The second is a shell-shocked soldier, the still-living specter of a man lost to war. The third is somewhere in the Philippines, missing in action. Finally, the youngest is a deaf photographer.

One of Tony Leung's best performances, Wen-Ching is the heart and soul of the flick, a silent observer of history whose gaze often feels like an in-film manifestation of Hou's camera. A City of Sadness is not an easy watch, demanding formidable attention while presenting a devastating tragedy. Its polyglot text – in Mandarin, Cantonese, Taiwanese Minnan, Japanese, and Shanghainese – asks the viewer to listen attentively to the idiomatic changes. The use repeated compositions render narrative as disruptions in cyclical imagery.

THE PUPPETMASTER (1993)

THE PUPPETMASTER (1993)

However, for those generous few who give themselves over to Hou Hsiao-Hsien's epic vision, A City of Sadness can be one of the defining cinematic experiences of one's life. If I ever write down a list of the best pictures ever made, you can be assured that A City of Sadness will be there. Many critics say the same thing about the director's follow-up, another period drama that looks back at the half-century of Japanese occupation. 1993's The Puppetmaster again refracts history through a humble biography, paying homage to traditional arts, those who keep them alive.

The film, which is in desperate need of restoration, marked the first time Hou Hsiao-Hsien competed for the Palme d'Or at Cannes. Though he lost the maximum laurel, the director took home a Jury Prize. However, this new peak of international recognition didn't reflect itself at home. So abysmal was The Puppetmaster's box-office performance that Hou was forced to reconsider his plans for the final picture in the historical trilogy.

GOOD MEN, GOOD WOMEN (1995)Having abandoned the plans to shoot the story of a midcentury man awaking from a decades-long coma to confront the realities of modern Taiwan, the director created a smaller-scale contrast between past and present. 1995's Good Men, Good Women juxtaposes the plight of a contemporary actress and her role as a Chinese resistance fighter who, having fought the Japanese during the war, was then victimized by the KMT. Personal and national crises become one in this palimpsest, scenes of meta-cinema blurring the lines that separate now and then, those who remember and what is remembered.

GOOD MEN, GOOD WOMEN (1995)Having abandoned the plans to shoot the story of a midcentury man awaking from a decades-long coma to confront the realities of modern Taiwan, the director created a smaller-scale contrast between past and present. 1995's Good Men, Good Women juxtaposes the plight of a contemporary actress and her role as a Chinese resistance fighter who, having fought the Japanese during the war, was then victimized by the KMT. Personal and national crises become one in this palimpsest, scenes of meta-cinema blurring the lines that separate now and then, those who remember and what is remembered.

In some instances, the same shot may bridge that gap, slow pans sometimes taking a single character across the years or even across history, reality itself. Despite his love for static master shots, Hou Hsiao-Hsien had been playing with another visual strategy since the late 80s, a roving camera that never stops floating through scenes. The modern-day scenes of Good Men, Good Women consolidated the technique as part of the director's auteurist style. The following year's Goodbye South, Goodbye expanded its possibilities, testing limits to such extents that the film feels like a treaty on cinematic movement.

GOODBYE SOUTH, GOODBYE (1996)

GOODBYE SOUTH, GOODBYE (1996)

Mark Lee Ping-Bin and Chen Haui-En's cinematography is masterful, showcasing how, in Hou's cinema, there's no discernable distinction between form and character, a camera and a heart. Narrative is repudiated for the sake of cinema as life, transitory passages bleeding in and out of moments untethered from a storytelling nexus. Looking back at the director's early work, Goodbye South, Goodbye comes off as a more mature brethren to The Boys from Fengkuei, perchance the Daughter of the Nile's metamorphosis.

Before the millennium was over, Hou Hsiao-Hsien would complete one other picture, his first set outside Taiwan and beyond the limits of living testimony. The Tony Leung-led Flowers of Shanghai is made up almost exclusively of one-shot scenes divided by fades to black. The film concerns a Shanghai brothel during the latter days of the Qing dynasty. As if intoxicated by the opium smoke, the camera drifts in precisely choreographed motions that delineate hierarchies of power and eroticism. It's an opulent period piece, intimate to the point of claustrophobia.

To watch the film is to be immersed in a tradition of sensualist cinema, here weaponized to deliver a treacherous plot full of whispered cruelties, the merciless motions of history, and the human heart's fatal tenderness. Languid to an extreme, Flowers of Shanghai is akin to a dream crystallized in celluloid, showcasing how Hou Hsiao-Hsien's cinema was slowly moving away from his neorealist origins as part of the Taiwan New Cinema movement. Henceforth, he would return time and time again to oneiric placidity while becoming more referential than ever before.

FLOWERS OF SHANGHAI (1998)Moreover, he continued to drift away, far beyond the Taiwanese borders, working in China, Japan, and even France. Tomorrow, we'll consider those films. Our retrospective shall end with Hou Hsiao-Hsien in the 21st century.

FLOWERS OF SHANGHAI (1998)Moreover, he continued to drift away, far beyond the Taiwanese borders, working in China, Japan, and even France. Tomorrow, we'll consider those films. Our retrospective shall end with Hou Hsiao-Hsien in the 21st century.

10|25|50|75|100,

10|25|50|75|100,  Asian cinema,

Asian cinema,  Cannes,

Cannes,  Chinese Cinema,

Chinese Cinema,  Hou Hsiao-Hsien,

Hou Hsiao-Hsien,  Taiwan,

Taiwan,  Tony Leung,

Tony Leung,  Venice

Venice

Reader Comments (3)

I have Flowers of Shanghai as a Blind Spot which I hope to watch later in the year when I get the Blu-Ray for that film.

I have Flowers of Shanghai as a Blind Spot which I hope to watch later in the year when I get the Blu-Ray for that film.

thevoid99 -- The Criterion edition is such a beautiful thing to behold. It looks much better than it did years before when I first encountered the film.