Boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into weak adaptations of great books

Thursday, May 9, 2013 at 9:45PM

Thursday, May 9, 2013 at 9:45PM  Hi all, Tim here. Like a lot of you, I’ve been waiting on Baz Luhrmann’s brand-new, all-3D, all-CGI version of The Great Gatsby with a kind of curious dread, on the assumption that the no-doubt overwhelming style and glitz would leave F. Scott Fitzgerald’s excavation of the limits of American ingenuity and self-invention a little bit lost amidst all the eye candy. And this seems to have been exactly the case, sadly.

Hi all, Tim here. Like a lot of you, I’ve been waiting on Baz Luhrmann’s brand-new, all-3D, all-CGI version of The Great Gatsby with a kind of curious dread, on the assumption that the no-doubt overwhelming style and glitz would leave F. Scott Fitzgerald’s excavation of the limits of American ingenuity and self-invention a little bit lost amidst all the eye candy. And this seems to have been exactly the case, sadly.

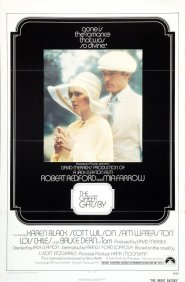

But let us not come down too hard on Baz. There’s also the possibility that Gatsby simply isn’t a novel that’s meant to be filmed, and as evidence I’d like to call upon the last feature film adaptation, and certainly the best known prior to now. Of course, I mean the 1974 Paramount production starring Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby, Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan, and Sam Waterston as Nick Carroway, and a general sense of lifeless ennui as the stimulus-crazed Roaring ‘20s. Other than a fixation on production design and costumes (it won the Oscar for the latter), there’s not much that the ’74 film has in common with Luhrmann’s screamingly excessive vision; if anything a bit more of a willingness to push against the book, rather than to so dutifully illustrate it in the driest way possible, might have benefited it. Movies are not books, after all, and this version of Gatsby badly loses sight of that truth.

Its overriding problem, even more than a desperately uneven cast, is a glassy-eyed literalism on the part of director Jack Clayton and the narration-heavy screenplay credited to Francis Ford Coppola (who flatly denied that the final version was based on his draft), less interested in exploring the pages of the book than unimaginatively reproducing them. Ironically, this means that the film completely misses the marks as an adaptation of Fitzgerald: stylistically, The Great Gatsby is famous for its efficiency and concision, painting entirely in short brush strokes that imply shapes without making anything needlessly overt. That results in a compact book that’s a swift read; but when it’s transliterated so dutifully to cinema, the result is the exact opposite: images lie there leadenly, as Waterston’s frequently redundant narration and Clayton’s static blocking of character scenes conspire to make every moment stretch out into oblivion. The book implies; the movie yells, and then yells a second time just to make sure we got it.

It’s attractive at least, and though the cinematography bears all the hallmarks of a 1974 production (browned-out colors, and zooms that exist solely to amuse themselves), at least Clayton and his DP, the ever-reliable Douglas Slocombe (later of the Indiana Jones movies), capture the exhaustively well-designed sets with a certain clarity of vision that does give the film an undeniable authenticity of place; as I am not 110 years old, I can’t swear that it looks exactly like the 1920s in Long Island, but it certainly looks like the place that Gatsby is meant to take place, even if some of its locations verge on the overwrought – the valley of ashes is presented less as a metaphor, more as an Eastern European war-zone. And we are brought into it effectively by the filmmakers, even though the act of bring us in is so exhaustive as to leave no space for drama or characters.

The characters… yes. About those actors, there’s no way around it: Redford and Farrow aren’t as good as they could have been. Farrow in particular suffers from a particularly bold and ineffective series of choices to play Daisy as an addle-headed ninny with a fluty voice (when she utters the famous line about Gatsby’s shirts, it sounds like Katherine Hepburn voicing a Disney princess), a propensity for staring, and absolutely no attention span from the very beginning, making her not at all a Fitzgeraldian emblem of the unattainable, but more of a dreadful bore, the sort you talk to just long enough to realize what a loud, self-involved flake she is before taking the first chance out of the conversation that presents itself. It’s hard to regard Jay Gatsby as a tragic figure for pining after her, or as anything but a masochist.

Redford himself is, if anything, worse; not in such a splashy way as Farrow, but the deeper into the movie we get, the more that his palpable unwillingness to play anything but the smiling matinee playboy gets in the way of the movie doing anything with its central figure (in his 1974 review of the film, Roger Ebert suggested that Redford and Bruce Dern, who plays Tom Buchanan, could have profitably switched roles; having read that, it’s impossible not to think of how much better Redford’s performance would have suited that arrangement). This Gatsby is already lumbering enough; it certainly doesn’t need Redford’s non-committal performance to make it shallow, as well.

Redford himself is, if anything, worse; not in such a splashy way as Farrow, but the deeper into the movie we get, the more that his palpable unwillingness to play anything but the smiling matinee playboy gets in the way of the movie doing anything with its central figure (in his 1974 review of the film, Roger Ebert suggested that Redford and Bruce Dern, who plays Tom Buchanan, could have profitably switched roles; having read that, it’s impossible not to think of how much better Redford’s performance would have suited that arrangement). This Gatsby is already lumbering enough; it certainly doesn’t need Redford’s non-committal performance to make it shallow, as well.

Weirdly, given how badly the leads misfire, most of the supporting cast acquits themselves well (though hampered, every one, by a tinny sound mix that makes everybody sound harsh); Waterston’s Nick in particular finds just the perfect register of being a half-sophisticated outsider, and the film’s next two biggest female parts, Tom’s mistress Myrtel Wilson and Daisy’s catty friend Jordan Baker, are excellently played by Karen Black and Lois Chiles, respectively, each of them using the same period trappings that imprison Farrow to find something real and lived-in about the women they’re playing. And so on and so forth, into the smallest roles. Cumulatively, they add enough vitality and humanity to The Great Gatsby that it doesn’t counteract the claustrophobic direction and aimless leads, but draw attention to just how much the movie is misfiring at its most important points. It’s the worst of both worlds.

I’m not going to make the claim that any of this is better or worse than Luhrmann’s overcaffeinated take on the material, just that it is, in and of itself, no tribute to the novel it so scrupulously embalms. We’ve now had a Gatsby that fails for being too earnest in its attempt to dramatize the book, and a Gatsby that fails for being too irrelevant and shallow (and a film noir Gatsby from 1949 – the mind reels), which pretty much covers all the bases, and maybe the lesson here is that not every prose masterpiece needs cinematic enshrinement. But I’m not holding my breath that anybody’s going to learn that lesson soon.

Reader Comments (14)

"...it sounds like Katherine Hepburn voicing a Disney princess"

i'm adding that to my list of things i didn't know i always wanted

par3182 -hee.

your takeaway "lesson" i think is just right. The prose is so fine in Fitzgerald's slim novel and so subtly evocative that film versions always seem excessive to me even before the excess extremes of Luhrmann. But here we are jumping ahead again.

but my favorite part of this review is "as I am not 110 years old"... it's so funny about authenticity with period pieces. it's like that famous line about obscenity. I don't know what it is but i know it when i see it.

I think you're probably right and the book has something that can't be taken from the page but the other day I read someone complaining that they couldn't like the book because it was all rich people problems and it occurred to me that a Sofia Coppola Great Gatsby could be exquisite.

SVG --- !!! now why didn't anyone ever think of that. Hers would be exquisite. She captures sensory experience and insular worlds so well. Not to mention how smart she is about POV. Great, now i'll be thinking about this all day.

Tim -- but don't you think it's worth seeing at least to see Robert Redford and Mia in all their finery? ...speaking of sensory experience

Bruce Dern as Jay Gatsby? I probably would have lost my mind.... in a good way.

Thinking of what a Redford-Dern casting switch would have looked like, how about a DiCaprio-Edgerton switch, with DiCaprio as the entitled petulant brat husband and Edgerton as the thug with a dream? But neither of those switches would have drawn the crowd in and made money.

Sofia Coppola would be great with this milieu, but I like the way she explores contemporary situations that intrigue her.

I do love book adaptations with their strong sense of character and narrative line, but I think you are so right that not every book lends itself to this. But then, I've loved books that I thought were unfilmable that made great movies, like Shoeless Joe.

Sofia has already kind of done a version of GATSBY with THE VIRGIN SUICIDES. Eugenides' novel, thematically, seemed to be pretty influenced by Fitzgerald, and I think Coppola did a great job of bringing that mood to the screen. Whenever I teach Fitzgerald's novel to my high school students, I make sure we watch Coppola's film as a supplemental text. The connections are definitely there. So, yes, I too would love to see Coppola tackle GATSBY because she seems like she would have an understanding of how to translate the stuff that really makes the novel so great onto the screen, rather than just focusing on the cars and the bootlegging and the girls and the parties.

Great stuff, Tim.

Well I'm not 110 years old (yet, hopefully?), but I do remember seeing The Great Gatsby more than once in the movie theater when it came out. I was probably 12 or 13 years old at the time. I thought it was fantastic of course because I didn't know any better. I still think the costumes, sets, and music are swell. I even bought the (double!) LP.

I wanted to live like Robert & Mia, and why didn't everyone? Even at that time I thought Mia was awfully blank, but I had no idea whether that was good or not. I've read the book subequently and I still don't know if her choices/limitations were correct for the role. I would really love to find out why they cast Mia Farrow in that role. She was a semi-star but she was no Barbra or Jane Fonda - both of whom would have brought a lot more electricity to the role.

Ang Lee might have done well by Gatsby. He's a visual maestro. And Life of Pi, the book that everyone thought unfilmable, became a fine, soulful movie.

It was actually Richard Brody's review of the movie that made me think, 'It seems DiCpario and Edgerton should have switched roles.', with the way he described the performances with DiCaprio having no roughness and Edgerton having too much roughness and none of Tom's refinement. I think the marketing could have worked its way around that kind of casting. Make Gatsby a mysterious, shadowy figure nobody really sees or runs into at the parties. That said, it would have been so risky.

Richard Brody also threw out Rooney Mara and Armie Hammer as Daisy and Tom.

"But let us not come down too hard on Baz. There’s also the possibility that Gatsby simply isn’t a novel that’s meant to be filmed"

Arguably, this means we should come down even harder.

Farrow does a nice job of capturing Daisy: she understands the indelicate balance between disillusionment and idealism. But Redford's bland presence gives her nothing to play off. She can't fully inhabit this woman with her co-star on auto-pilot. Redford can be great, but he pulled the same thing in Out of Africa--trading on his movie star persona rather than actually acting.

Late to the party, but the idea of Sofia Coppola directing The Great Gatsby is so perfect that I will be never stop being angry that it won't actually happen.

@Nathaniel: as far as pretty movie stars in finery goes, I'll admit that for me Leo + Carey + Catherine Martin > Robert + Mia + Theoni Aldredge.

Great post, and also well written and well explained, truly amazing, in mean time you can find tubemate apk ios on our this page and get much more in the movies section and songs etc.

Many many thanks