Exploring the Humanity of Deafness in "Wonderstruck"

Thursday, November 9, 2017 at 8:00PM

Thursday, November 9, 2017 at 8:00PM By Spencer Coile

At my showing for Wonderstruck this week, there were only six other people in the audience: a young couple and a gaggle of older ladies who felt comfortable talking their way through the whole movie. And while I was initially annoyed at this inconvenience, I was instantly sucked into the world Todd Haynes assembled in his period piece about loss, life, and the family we seek comfort in. Something was especially strange about my experience, though -- the entire film played with subtitles. Was this intentional and I just didn't know it was supposed to be shown this way? Was this a mistake by the theater? Or did one of my fellow moviegovers request this specifically?

These questions were never answered, but it didn't matter. I personally consume all my media with the subtitles on, so this was a total delight. But how perfect it was to sit back and enjoy a film that celebrates our differences (one of which being the characters' deafness) while also incorporating a feature that is used to help enhance movie watching for those who are visually impaired. And so it began: Wonderstruck, another story suitable for Haynes' illustrious career.

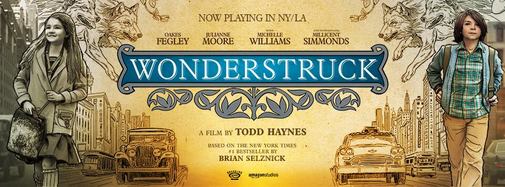

Unlike many of Haynes' past films, Wonderstruck works because of its seemingly low stakes. Of course, there is conflict. We see the juxtaposition of two stories in two separate time periods: one in 1927 where Rose (Millicent Simmonds) reconciles with her deafness and one in 1977 where Ben (Oakes Fegley), recently deaf, runs away from Minnesota to New York City to find the father he never met. This is further compounded by the visual components of each time period -- the music, the color (one is black and white, the other uses vibrant colors), and the differences in costuming. Yet, as we jump from story to story, Wonderstruck feels as though it were floating on a cloud. The editing is seamless, shifting from one scene to the next in a way that tells us that these stories are intrinsically linked. And indeed they are, but the build-up to this moment takes its time, allowing us to soak up each tiny moment and enjoy the journey that these characters are on.

More than anything, Todd Haynes is a visual storyteller. His stories are rich and his characters are well-developed, but without fail, he will assemble a crew that provides the richest production design, cinematography, and score. Fortunately, Wonderstruck is no exception. Considering the film's story is based off Brian Selznick's book of the same name, a book that relies heavily on images and pictures over the written word, it is no wonder that the film must be visually appealing in order to pop on the big screen. Each of these visual elements help to give the film that storybook quality, one that really does seem to come to life from the page. After all, for these two children, it is what we see, rather than what we hear, that truly matters.

Mark Friedberg -- whose career notably includes Synechdoche, New York, another film focused on world-building -- provides the film with set designs that are brimming with possibility, as if we too could discover something new around every corner. And Carter Burwell explores the relationship between these two time periods in ways that make them different, but somehow very similar. The score is equally whimsical and beguiling, because it brings to life the words these characters cannot say.

I've heard many people refer to Todd Haynes' filmmaking as cold or detached. It is all visual flare with no heart underneath. However, sitting in an almost empty theater, watching this story unfold before my eyes, I could not help but feel that Wonderstruck was anything but detached. In the final 15 minutes, as all of our questions are finally answered, I found my heart swelling with the score, crying when our protagonists cried. In just two hours, Todd Haynes broke my heart and miraculously put it back together again. The film glides into a sweet and satisfactory conclusion, one that relies less so on the spoken word and more on what we see before our very eyes. And although the subtitles were still on by the end, I realized that in Wonderstruck's final moments, we may not have needed them after all.

Grade: A-

Reader Comments (7)

I want to see this. Todd Haynes puts my ass in the seat!

I hope it will be released in Italy soon. I adore Haynes.

It's obvious that the subtitles are there because the main characters are deaf. The film will attract many deaf people. So the logical thing is to cater to their need so that they don't have to wait until the film comes out on DVD.

My screening also had "open captions," which I was a bit taken aback by. When I looked closer at the fine print on the theater website it appears they were doing it for all showings. I don't know if that's the case for all showings nationwide or if it's a decision being made at each theater.

I loved this movie. During the first minutes of the film, I whispered to my companion, "what's going on with the subtitles?". Because I tend to watch a lot of international TV (or at least a bunch based in the north of England) I also watch most things with subtitles on. No biggie.

Haynes has a lovely way with pacing and visuals. This film was so much better than the other Selznick adaptation (Hugo). Also, major kudos to the casting team who found perfect child actors, because Williams and Moore probably have less than 15 minutes screen time combined.

Highly recommend to anyone who just needs a break from our cold reality.

My showing did not have subtitles, so I don't think the film is intended to show that way. However, perhaps Haynes should have gone with that idea.

Mine had subtitles as well, though I can't find a definitive one-way-or-the-other on whether it was intentional or not. Either way, it was a lovely decision (and the movie was lovely too, even if I wasn't as fond of the pacing as some).