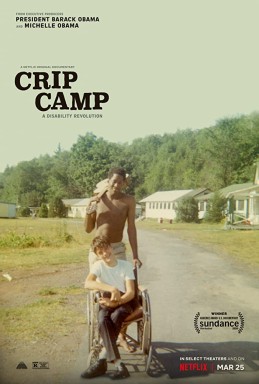

Doc Corner: Is 'Crip Camp' an early Oscar frontrunner?

Wednesday, April 15, 2020 at 4:00PM

Wednesday, April 15, 2020 at 4:00PM By Glenn Dunks

As if on cue to allow isolated audiences one hell of an emotional purge, James Lebrecht and Nicole Newnham’s sublime Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution is here. Seemingly built to make audiences burst into tears out of honest to goodness heart-melting positivity and righteous activist anger in equal measure (a delicate balance to say the least), it is perhaps for the first time since this pandemic began that I contemplated my own small place in this big world outside of COVID-19.

As if on cue to allow isolated audiences one hell of an emotional purge, James Lebrecht and Nicole Newnham’s sublime Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution is here. Seemingly built to make audiences burst into tears out of honest to goodness heart-melting positivity and righteous activist anger in equal measure (a delicate balance to say the least), it is perhaps for the first time since this pandemic began that I contemplated my own small place in this big world outside of COVID-19.

It’s big-hearted and impassioned; an unsurprising winner of Sundance’s audience award and an obvious frontrunner for the Academy Award.

In a small fielded summer camp outside of Woodstock, NY, a collection of teenagers with disabilities gathered at Camp Jened. Like any able-bodied campers in life or in the movies, they play sports and they complain about the food and they get horny. Very, very horny. Away from the experience of being othered by a society that was even more cruelly dismissive towards those with disabilities than today’s, this group of young individuals have voices that are patiently listened to with opinions that are so often kept ot themselves. I found the experience of witnessing this wonderful passage of Crip Camp—captured in soft-fuzzed video; I was so happy the directors and editors Andrew Gersh, Mary Lampson and Eileen Meyer allowed it to run as unabridged as possible—so humbling to whatever ableism that may subconsciously be nestled within me.

The taboo of speaking their complex emotions is obliterated at the camp and what they have to say ought to be vital and real to anybody. This continues throughout the documentary once the film leaves the camp—and considering the title, people may be surprised how much of Crip Camp is set in the years following that particular year’s intake of campers have left the grounds—as Lebrecht and Newnham reconvene many of the surviving members for recollective talking head interviews and heartfelt reunions, including Lebrecht himself who has spina bifida and is in a wheelchair. As we peer into their lives, they are forthright and open about not just the daily struggles (the tribulations of public transport, the desexualization of people with a disability, the smothering of parents) and the larger issues around the desire to be an active participant in a society that for so long has excluded them because to do otherwise costs too much or takes too much of an effort (note the NYC metro's locking up of subway entrances to skirt accessibility requirements).

The majority of the brisk 106-minute runtime is devoted to how these men and women left Camp Jened and took their experience of independence and responsibility and applied it to the disability rights activism movement that was emerging in the 1970s. Led most fiercely by Judith Heumann, their stories tell of protest both political and social. They took to the streets and to Washington in a bid to fight for the civil rights they deserved and demanding to not just be grateful for one disabled toilet in an office but to be able to get an education wherever they want, work where they want, and live outside of the institutions and homes that (as seen here through news reporting by Geraldo Rivera) treated them as monsters and freaks in grotesque squalor.

I knew much of this thread of the story, having seen Sarah Barton’s 2017 Australian documentary Defiant Lives. The two films share archival footage including that of key figures as well as the likes pf George H.W. Bush as he signed the ADA legislation or the deeply affecting Capitol Crawl up the steps of the U.S. Capitol Building, although that earlier film stretched its parameters to Australia and the UK, as well. Not that there aren’t lessons that shouldn’t be taught repeatedly, and the directors here are smart to tie the experience at Camp Jened with this breeding of a generation of activists in the same way any coming of age movie would. In a way it connects their fight to something for the assumed predominant able-bodied audience. A way into their rich lives that disassociates them from, as one subject notes, the cloak of victimization that many able-bodied individuals have seen in them for decades.

The best comparison I can actually come up for here is The Times of Harvey Milk, Robert Epstein’s 1984 Oscar-winning documentary. Like that one, Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution is both a peas-and-carrots style history lesson, its filmmaking unflashy yet well assembles, as well as an entertaining and engrossing work of filmmaking. It’s good for both the mind and the soul. It has enough of a social sting, but also finds deep wells of humanity. I was profoundly moved.

Release: Currently streaming on Netflix.

Oscar chances: Its theme, plus its boomer-era setting, plus Michelle and Barack Obama’s stamp of approval (it comes from their Higher Ground company, which also helped bring this year’s Oscar-winning American Factory to us), plus a potential lack of documentaries released this year mean it’s an early favourite. I know its deeply cynical, but if voters want a moment on the ceremony, having their first wheelchair-utilising winner would be one.

Crip Camp,

Crip Camp,  Doc Corner,

Doc Corner,  Harvey Milk,

Harvey Milk,  Review,

Review,  documentaries

documentaries

Reader Comments (1)

Rousing Netflix documentary traces disability rights movement games and folk singalongs, furtive makeouts in dark corners. a “radical, early video coalition of hippies” who stopped by the camp is what my thought on this beautiful documentary.