Nothing about Ava DuVernay’s career up to 2014 suggested the epic sweep of Selma. I Will Follow and Middle of Nowhere are both quiet dramas, focusing on one central character and a handful of supporting players as they navigate a major, life-altering event. Race is the background against which these stories are set - coloring a heated music discussion, or shading the convict’s biased parole hearing - but racism isn’t explicitly addressed. This changes dramatically with Selma. In a year that has seen protests in Ferguson and serious discussions about diversity in the Academy, Selma has been called everything from controversial to current to incorrect. For its director, it’s proof that 6 years and 3 movies can rapidly mature a talent.

When telling the story of Martin Luther King’s 1965 protest march in Alabama, DuVernay focuses not on a man, but on a movement. She studies the Civil Rights movement as if it were a character, following not only Dr. King’s glossy speeches, but also the many behind-the-scenes maneuvering. King’s arguments with President Johnson, Johnson’s arguments with Governor Wallace, the student organizers’ arguments with King’s men, even quieter discussions between Coretta Scott King and Malcolm X expose the precarious balance between ideology and strategy that's needed to succeed. DuVernay manages to write her characters with humanity as well, populating the film with people, not symbols. Early on, Dr. King (dignified David Oyelowo) comments lightly that the reason he's in Selma is because he needs a bully to catch national sympathy, and the racist sheriff is that man. As men start dying, those words hang over King's head like a cross.

If I have one complaint with Selma, it’s that the violence is too beautiful. DuVernay deftly stages the action of hundreds of protestors for the camera, and re-teams with cinematographer Bradford Young. The result is similar to Raging Bull: every protest is shot differently, so that each violent outbreak feels fresh. If the night march feels familiar to 2014 audiences, if the first march feels claustrophobic, if the violence on the Edmund Pettus Bridge looks like a hallucinatory war film, that’s not unintentional. In Selma, Ava DuVernay has matched epic sweep with humanity and brutal vision. It’s a hell of an achievement for a third film.

This close to the Oscars ceremony, reviving the question of whether Selma was snubbed is pointless. But regardless of Sunday’s outcome, Ava DuVernay has joined a different illustrious company: unnominated female directors whose films were nominated for Best Picture. In an attempt to divine DuVernay’s future, I did some research, and discovered a pattern: Of these nine female directors, seven are still directing. Of those seven directors, four (including DuVernay) are now working in TV.

As anyone with a remote or a streaming subscription knows, we are currently in a second Golden Age of television. This is due in no small part to the diversity of creative talent. Every year, more shows are created by, directed by, and starring women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community. In this increasingly colorful TV landscape, Ava DuVernay will be a welcome addition when she launches her show on OWN. But at what cost to film?

2014 has been widely criticized as the whitest, most male-dominated year of the Oscars in a long time. As much as I would like to blame our old scapegoat, the White Male Voter, this is also because of the homogeny of the films being offered to the Academy. When we can count the number of Oscar nominated female directors on one hand--likewise for directors of color--we should be shouting for more of these voices in film, instead of celebrating when the ones who’ve already proven themselves move to television (where they can get snubbed by the Emmys instead). I love Ava DuVernay’s work. I can’t wait to see what she creates with Oprah’s blessing. But surely I’m not alone when I say: Ava DuVernay, please come back to film soon.

2014 has been widely criticized as the whitest, most male-dominated year of the Oscars in a long time. As much as I would like to blame our old scapegoat, the White Male Voter, this is also because of the homogeny of the films being offered to the Academy. When we can count the number of Oscar nominated female directors on one hand--likewise for directors of color--we should be shouting for more of these voices in film, instead of celebrating when the ones who’ve already proven themselves move to television (where they can get snubbed by the Emmys instead). I love Ava DuVernay’s work. I can’t wait to see what she creates with Oprah’s blessing. But surely I’m not alone when I say: Ava DuVernay, please come back to film soon.

Thus concludes our first month of Women's Pictures. Next week will be a vote to choose our next female filmmakers. Who do you want us to cover? If you have suggestions for future Women’s Pictures directors, post them in the comments or find Anne Marie on Twitter!

Sunday, November 27, 2016 at 4:00PM

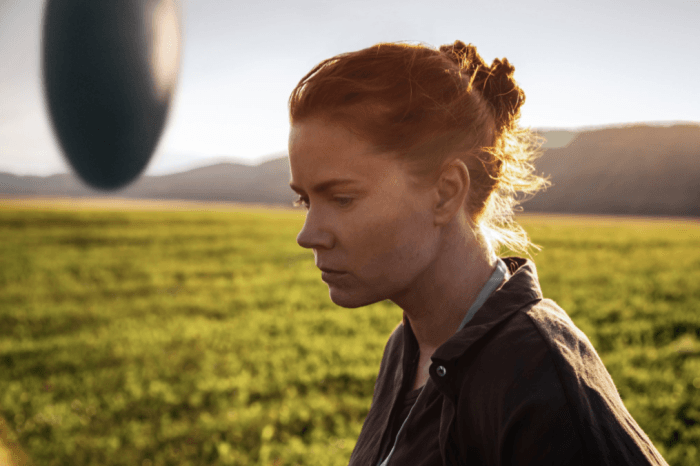

Sunday, November 27, 2016 at 4:00PM  Chris here to spread some love for one of my below the line favorites in this year's Oscar Race. Like many of my cohorts here at The Film Experience, I am completely taken with Arrival. Director Denis Villeneuve's last two films (Sicario and Prisoners) resulted in Best Cinematography nominations for the genius Roger Deakins, but this time he partnered up with future legend Bradford Young to stunning results. If the Oscars want to reward some diversity below the line, Young is a mightily deserving talent.

Chris here to spread some love for one of my below the line favorites in this year's Oscar Race. Like many of my cohorts here at The Film Experience, I am completely taken with Arrival. Director Denis Villeneuve's last two films (Sicario and Prisoners) resulted in Best Cinematography nominations for the genius Roger Deakins, but this time he partnered up with future legend Bradford Young to stunning results. If the Oscars want to reward some diversity below the line, Young is a mightily deserving talent.