Dear Ingmar...

Thursday, February 21, 2013 at 11:00PM

Thursday, February 21, 2013 at 11:00PM Hi lovelies, Beau here with something that plastered a big smile across my face today:

It's a fan letter from Stanley Kubrick to Ingmar Berman. Text after the jump...

The Film Experience™ was created by Nathaniel R. All material herein is written by our team. (This site is not for profit but for an expression of love for cinema & adjacent artforms.)

Follow TFE on Substackd

Thursday, February 21, 2013 at 11:00PM

Thursday, February 21, 2013 at 11:00PM Hi lovelies, Beau here with something that plastered a big smile across my face today:

It's a fan letter from Stanley Kubrick to Ingmar Berman. Text after the jump...

Monday, October 8, 2012 at 6:00PM

Monday, October 8, 2012 at 6:00PM Michael C. here with a look at one of the under-the-radar festival hits appearing the NYFF.

One of the subjects of Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 is convinced that Kubrick’s The Shining is the director’s thinly veiled confession that he helped NASA fake the moon landing. He admits at one point to wondering if his idea stretched plausibility, but he adds that any doubt went out the window when he spotted the image of the Apollo 11 rocket on young Danny Torrence’s sweater in a pivotal scene. What other explanation could there possibly be for Kubrick the perfectionist including such a thing?

This is the refrain all the subjects of Ascher’s documentary return to as they unspool their elaborate theories about the supposed hidden meanings of the horror masterpiece: Stanley Kubrick was a master, a control freak, a genius. Nothing ever found its way into his films by accident. To hear them speak, every detail, no matter how incidental, was one more ingredient in the filmmaker’s complex web of symbolism. Theories range from The Shining as a commentary on the genocide of the Native American, to a reading of the story as an allegory for the Holocaust.

By opting not to show any talking heads Ascher grants all the speakers equal footing, combining their words into an aural labyrinth of competing evidence. Some of their analysis is compelling. An attempt to map the floor plan of the Overlook Hotel reveals how rooms appear to shift and disappear from scene to scene. Other digressions are straight up kooky, as with the moon landing theorist’s proposition that the capital letters on a key chain marked “ROOM No. 237” are a subliminal attempt on Kubrick’s part to plant the words MOON and ROOM in the mind’s of audiences. (The film is too kind to point out they can also be arranged to spell MORON)

What keeps Room 237 from merely being an overblown DVD bonus feature is the cleverness with which Ascher uses the minutiae of the theories to explore the way our minds hunger to find meaning wherever we look. Our brains our designed to find connections, Room 237 says, and The Shining with its bottomless subtext, inexplicable imagery, and seemingly deliberate continuity errors provide a playground where such impulses can run amok.

At the center of the doc’s hedge maze of theories is Kubrick himself, still mysterious, still elusive as ever. Room 237 works broadly as a meditation on the relationship between artist and audience, but more specifically as a demonstration on the continued hold Kubrick has over audiences. Room 237 is a smart, engaging, often funny film. Should Ascher ever decided to apply the technique to other films I would be interested to see the results, even if another attempt may not work as well without Kubrick on hand to toy with our minds. B

More NYFF

Lincoln's Noisy "Secret" Debut

The Bay An Eco Conscious Slither

The Paperboy & the Power of Nicole Kidman's Crotch

Bwakaw is a Film Festival's Best Friend

Frances Ha, Dazzling Brooklyn Snapshot

Barbara Cold War Slow Burn

Our Children's Death March

Hyde Park on Hudson Historical Fluff

NYFF,

NYFF,  Rodney Ascher,

Rodney Ascher,  Room 237,

Room 237,  Stanley Kubrick,

Stanley Kubrick,  The Shining

The Shining  Tuesday, May 22, 2012 at 9:04AM

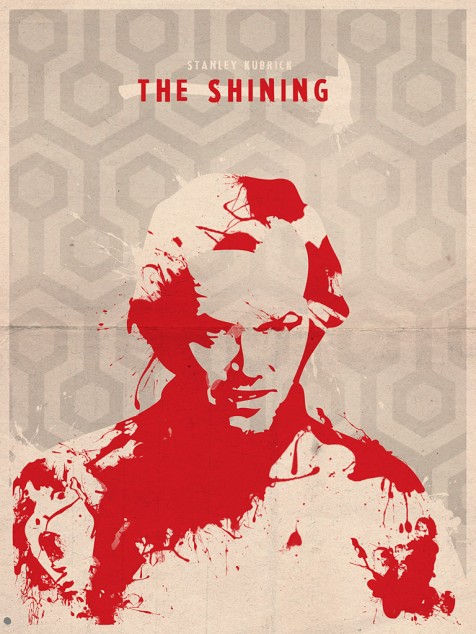

Tuesday, May 22, 2012 at 9:04AM  Poster design by Matt HightowerAlexa here. 32 years ago this very week, Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of The Shining opened in theaters. Kubrick's masterpiece received mixed reviews and, at least initially, the audience was similarly befuddled. (My parents love to tell me that when they saw it opening weekend the audience frequently erupted in laughter.)

Poster design by Matt HightowerAlexa here. 32 years ago this very week, Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of The Shining opened in theaters. Kubrick's masterpiece received mixed reviews and, at least initially, the audience was similarly befuddled. (My parents love to tell me that when they saw it opening weekend the audience frequently erupted in laughter.)

It was nominated for two Razzies and zero Oscars.

Despite Stephen King's continued distaste towards it, the film's intrigue continues to grow (for evidence, just watch Room 237). I thought it the perfect time to mention one of my favorite Tumblrs, The Overlook Hotel, a wonderful archive of ephemera, fan art, interviews, and video related to the film.

Like this Scatman Crothers portrait "Shine Baby Shine"

“Shine Baby Shine” by artist Quyen Dinh.

“Shine Baby Shine” by artist Quyen Dinh.

Click for more Overlook treasures including caricatures and letterhead.

Thursday, March 1, 2012 at 3:00PM

Thursday, March 1, 2012 at 3:00PM Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film.

We shouldn't be talking about these things. And by "these things" I don't necessarily mean sex in general. Sex is okay filtered through the acceptable narratives of or cinematic pop-cultural lexicon. The happy conquests of the charismatic man are a fine topic for a film, as are the the constant failings of the empathetic dope. The female sexual experience is okay as along as it kinda mimics the male sexual experience. Basically we're willing to watch attractive actors an actresses roll in the sheets as long as their sex lives are at their own command. We do not take well to stories of people whose sexual desires do the controlling.

Lolita's Humbert and Shame's Brandon are two such people. Though it seems like they have it all. They're attractive, rich, sophisticated, educated and lead lives of effortless good fortune. Brandon's good looks and success place no limits onto the conquests craved by his sex addiction. Humbert's ridiculous luck places him as the sole guardian of a pretty young girl whose already had just enough experience to alleviate him from any guilt. The only thing Humbert and Brandon lack is someone else to blame.

As spectators to their inevitable downward spirals, it's difficult to watch them make all the choices that lead to their sad end and then feel sorry when they get there, especially when they leave casualties in their wake. The films they inhabit don't ask us to sympathize for them with a wink of dramatic irony like A Clockwork Orange or The Godfather (both great films) do with their protagonists. Instead they ask us to observe and then try to grasp the incredibly complex realtionship we have with the power of our own desires.

This is such an easy source of drama that on most any evening you can find television shows about addicts and hoarders and attempted interventions. On most supermarket shelves you can find magazines with tales of celebrities suffering from addictions. Psychological damage sells. The best of these paint complex portraits of real people trying to survive in a world that demands they be at war with themselves. The worst of them gleefully invite us to shed our empathies and delight in the chaos. It's difficult to have empathy for someone like Brandon whose problem includes attracting a plethora of beautiful women that would make any man jealous. And it's even more difficult to have empathy for someone like Humbert who preys on children.

Add to this the fact that both films omit any context in which to place our sympathies. Shame clearly suggests that Brandon has been damaged somehow, but we never know how. The most common criticism of the film is of its lack of backstory. But I wonder if such details are relevant. Do certain backstories justify his behaivor while others don't? Or would some at least invite our sympathy more than others? It's easy for us to postpone our emotional investment in someone until we have more details. But that's not what the movie asks of us.

In the case of Humbert, while the novel Lolita clearly sets up his penchant for young girls, the film omits this entirely. I've often wondered how viewers in 1962, who didn't have the backstory of the book reacted when their hero began to covet the young Dolores Haze. Of course the film had little choice than to convert the story into comedy to soften the blow. But there's still a surprising amount of drama and suffering to be had among the proceedings. And comedy or drama, there's only so much you can tiptoe around the central plot of a man lusting for an adolescent.

Then there are the other victims of these men's desires. Brandon's severly depressd sister Sissy, who pursues her sexual needs just as nihilistically as Brandon, but has to be chided and demeaned for it. And there's Humbert's Dolores, who has little time in life to be anything other than an object of temptation. Even her mother, the comedic relief, bumbling, boisterious Charlotte doesn't deserve her fate.

Which leads us to the real question that both of these movies are asking, whether either of these men truly deserve their fates. It's a complicated one, and based on the way audiences have reacted to these stories, over the past few months or past few decades it's a question we're still nowhere near answering. I imagine there's more goodwill present for Fassbender's Brandon since he's not involving himself with anyone who can't give legal consent (yet I can assume that more good judgment has been unknowingly discarded as a result of Fassbender's piercing gaze than Mason's droll sophistication). Then again, Humbert gets what's coming to him. He ends up punished for his crimes. Brandon merely ends up once again at the beginning of the cycle. What goodwill does that invite?

Perhaps the moralities of these films are so difficult to digest because they present not a simple world of monsters and victims, but a complex one of hurt people who hurt people, where the only monsters are us, when we look the other way and demand an easier reality.

Friday, December 30, 2011 at 10:40PM

Friday, December 30, 2011 at 10:40PM Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film.

It's not exactly the secret of the cinematic year that Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey and Terrence Malick's Tree of Life are two films of a similar kind. Indeed as Tree of Life hype grew to its crescendo this past spring and reviews started hitting the web it seemed like almost a requirement for writers to reference the 1968 science fiction classic. There were, I think, three reasons for this. First, which we'll get to shortly, that the two films do indeed have much in common in terms of theme and narrative. Second that both are epic length stories that many cinephiles consider high-water marks in the medium, and finally the involvement of Douglas Trumbull whose special effects work helped realize 2001: A Space Odyssey. When it was announced that he'd be working on The Tree of Life and creating sequences of a cosmic nature, the inexorable relationship between these two movies seemed predestined, and no one had even seen the Malick film yet. But with all the hooting about space and science fiction and experimental narrative and Trumble effects, the connection between 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Tree of Life now feels more like a solid fact to state and less like a flexible area to explore. So let's explore it.

Questions about the meaning of life, ponderances about the origin of the world and wonderment about how it all connects isn't a new or even unusal theme in moviedom. But most of the time, in fact almost all of the time, filmmakers feel the need to create an onscreen surrogate for both themselves and the audience to ask these questions. So most films about the meaning of life involve a solitary figure, a writer or an artist or a chess-playing knight meandering about wondering out loud what it all means. In movies about the meaning of life, it is the goal of the protagonist to find the meaning of life. Not so in The Tree of Life and 2001. While characters do ponder big mysteries, it's the narrative itself that takes us to the origins of creation. And to be clear, I'm using the term "origins of creation" pretty loosely here applying it to both the big bang for The Tree of Life and the early evolution of man for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Events past, much like stars in the sky, seem to be much farther from us and closer to one another than truth would have it. But in each film, the point is the same, that the events that will make up the significant dramatic conflict in the picture mean very little without cosmic context.

This context involves where we've been, where we are, and where we're going, scientifically & religiously speaking. The purpose of showing both the grandeur of the universe and the primal nature of man's past is to suggest our smallness and the smallness of the characters in these films. To them, their lives and their conflicts are the encompass of their universe. But in the scope of history, they are miniscule. Malick and Kubrick do this by creating worlds that at first seem dissimilar but upon further investigation are very alike. If there's any consistent criticism of Stanley Kubrick it's that he is a "cold" director, caring less for his humans than for his technique. 2001: A Space Odyssey plays into the hands of this criticism, featuring stoic human characters and providing our only emotional payoff from the mind of a machine. This seems in great contrast to Malick's film about the daily life, fears, loves and feelings of a family. But Malick's filmography has always presented us with the image of a harmonious world invaded by human violence, apathy, and destruction. The present set segments of The Tree of Life (the ones featuring Sean Penn that have been criticized as a somewhat pointless framing device) show us a world constructed, or is that destructed, by modern technology, and are as cold and austere as anything found in a Kubrick film.

But neither director holds as much ill-will toward the human race as you may suspect. Both films ultimately take us to our unknown future, whether that be the future of one man or all of humanity is, in both cases, ambiguous at best. Interpretations of the "star child" into which astronaut Dave Bowman turns at the end of 2001 are varied and range from the suggestion of alien manipulation to natural evolution to spiritual rebirth. Kubrick's film's finale may generally be considered more atheistic than Malick's but even the then pope (John Paul II, quite the film buff) was said to be a fan and considered the film one of great spirituality. This spirituality is how most people have viewed The Tree of Life's final sequence which presents us with a "heaven" that doesn't exactly adhere to any specific religion's interpretation of such a place, but still seems to present man's ultimate destination as one of great peace, community and beauty. In addition to this, both films seem to view mankind's journey to this ultimate destination as one essentially intertwined with the act of creation and the relationship between the creator and the created, whether it be ape and tool, parent and child, scientist and AI, god and man, and may I add, filmmaker and film. The message seems to be that it is creation that give us meaning, and advances us from insignificantly miniscule and suffering to, ultimately, a state of grace.

Other Cinematic Relatives: Such is the uniqueness of these two films, no other were immediately apparent to me. I'll let you fill in your suggestions in the comments.