Sandy Powell as an auteur and the splendor of 2002

Thursday, June 11, 2020 at 9:30AM

Thursday, June 11, 2020 at 9:30AM

Auteur theory may be important, but it has clear limitations. Cinema is an intrinsically collaborative art form and the creation of the cinematic object often involves the work of numerous artists brought together by a common creative mission. To point at one of those minds as the singular visionary of a film is, in part, to erase the authorship of the others. Over the years, scholars, critics, and casual cinephiles have argued for the auteur description to be expanded beyond directors, often signaling actors and writers as good candidates for that same validation. I'd argue that all sorts of contributors to the construction of cinema can be seen as artists who bring their authorial voice to their filmography.

For example, costume designers like Sandy Powell may putatively work for their director's grand vision. However, if you look at their filmography, you see recurrent obsessions and mechanisms, repeated themes, and the development of a personal aesthetic that transcends the limits of directorial intent. Since we're celebrating the year of 2002 because of the impending Supporting Actress Smackdown, I invite you all to consider Powell's authorship as we explore her fabulous designs in Gangs of New York and Far from Heaven…

Over the past two decades, Sandy Powell and Martin Scorsese have worked in seven projects together, both influencing each other in notable ways. It all started in 1999 after Powell had won her first Oscar for Shakespeare in Love. She got a call asking for a meeting with Scorsese, who was a fan of her work, and wondered if she'd be willing to read a script and consider designing a period film to be shot in Rome. The clotheshorse director and the glamourous costume designer got along like a house on fire and before they knew it, they had embarked in the joint challenge of bringing to life 1860s New York in all its splendor and squalor.

By the designer's own words, Gangs of New York was probably the most difficult project of her career, both because of its subject and the sheer scale of the enterprise. Developing the idea for an epic about 19th-century urban warfare since the late 70s, Scorsese had come up with a production of massive proportions that brought to mind the Italian epics of Sergio Leone and the extravagant designs of Fellini's dreams. With one foot in historical recreation and another firmly planted in the land of whimsical spectacle, Scorsese and his team turned the past into a pop opera. This mythical approach to the real-life story of the Five Points gang conflicts is clear from the very first sequence.

Moving through Dante Ferretti's gigantic Cinecittà sets, the audience is introduced to a world that's as rich in gritty palpability as in romantic abstraction. An old brewery is full of worn-down textures, signs of accumulated degradation, but it also feels theatrical in a way that defies the realism of its surfaces. As the cast walks out of the cavernous interiors into the open air and we get a glimpse of the snow-covered landscape, Powell's costumes start to take center stage. Over the snowy white background, actors and extras paint streaks of red and blue. The Irish Catholics are dressed in a chaotic assortment of red-dyed clothing, their poverty as evident as their rage. As for the Protestants, they're warriors adorned in pristine blue cloth.

This is a battle of gangs and it's also a battle of fashion. It's the American flag exploded unto costume and scenery. With such stark contrasts and color symbolism established, one would expect Powell to lean onto this palette, but her approach is never so dogmatic as that. As the film abandons this 1840s prologue and jumps to the Civil War years, Powell twists the iconography she has built. Ferretti's sets maintain strict aesthetical logic, but the wardrobe is more riotous and ungainly. The costume designer evokes the historically accurate silhouettes of the period but is quick to subvert their elegance with a storm of textiles that never seem to cohere but conjure a sense of organized chaos.

One thing that's present in every Powell flick is a preponderance of pattern and bright colors, costumes that call attention to themselves even when the camera doesn't pay them any mind. Think of The Irishman's bright ties or the luxuriant furs of Carol, the bold colored court of The Young Victoria, or the glam rock hallucinations of Velvet Goldmine. Gangs of New York is no different, but here the dials are turned to eleven, with every extra an individual storm of thrifting fabrics. The violent narrative may make the streets of New York run with blood, but Powell makes them run with Aniline dyes in all the shades of the rainbow. For such a gritty movie, the costumes are curiously closer to the color palette of a Pride parade than that of a cemetery.

It's not just a matter of chromatic chaos and textile juxtaposition. Powell is equally canny in her delineation of social hierarchies and character specificity, going from the most cerebral details to the most instinctual. Notice, for instance, how she suggests the poverty of the settings, aging fabrics, and covering clothing in signs of wear and tear like pacthes and pintucks made to fit the same garment to different bodies. Then there are things like the finery of Daniel Day-Lewis' Bill the Butcher, a bloodthirsty dandy whose costuming has as much to do with psychological clarity as it does with the actor's body. To make him stand out, Powell chose to highlight Day-Lewis' lean verticality, exaggerating proportions in a way that makes him look slender and imposing. Bill's authority is expressed, equal parts, in violent action and stylistic brio.

For her efforts in the Scorsese helmed picture, Powell got a well-deserved Academy Award nomination, but that wasn't the only Oscar-worthy wardrobe she designed in 2002. Far from Heaven is an even better showcase for Sandy Powell's particular genius and how her artistic vision may be in symbiosis with that of her directors but is never submissive to them. The 1957 set film directed by Todd Haynes is an homage to Douglas Sirk's classic melodramas, aping their aesthetic but making explicit what 50s filmmakers never could. It's all a game of repression and expression where cinematic language articulates what the characters cannot. In Far from Heaven, societal expectations are a muzzle, but the artifice of cinema is a megaphone.

As for Powell, she follows this logic but doesn't stick to it religiously. For instance, while Haynes carefully color-coded script is all about color harmony, Powell invests a lot of her artistry in emphasizing the tactile quality of clothing. Look at the plush velvets and soft silks, the crispness of a taffeta skirt, and the luscious warmth of a fur stole. Powell is referencing Sirk's cinema, but her surfaces are richer than the ones in the old master's pictures. Sirk was making a cinema of subversive glamour, while Powell's looking for something that transcends the subversion. The clothes in this film don't just copy the 50s styles, they breathe life into an imaginary past and entice us to reach out and touch. More importantly, these costumes only look real up to a point.

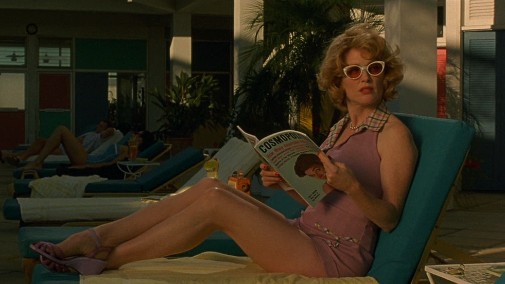

Unlike what she did in Carol, Powell isn't trying to construct a sense of immersive reality with a basis on historical fact. Far from Heaven's wardrobe is too pristine for that, drawing from the fantasy of 50s cinema rather than the reality of the period. Both Haynes and Powell are dissecting melodrama, their social commentary always observed through a prism of earnest fakery. That is never more obvious than when observing how Powell's costumes play off Mark Friedberg's sets. If you pay attention, you'll notice that Cathy and Frank Whitaker often match the environments they inhabit. They are a continuation of the décor, more objects than people, a facsimile of humanity that only looks at home in the photo spread of a glossy magazine.

Julianne Moore's Cathy takes this to ridiculous extremes. She not only matches the interiors of 1957 America, but she's equally in tune with the autumnal colors of the Connecticut outdoors and even the garish lighting with which Ed Lachman paints the night. During a pivotal scene, Cathy stands on her front lawn with a group of other women, all of them draped in the shades of orange and rust of the Fall landscape. Only a lavender scarf on our protagonist's neck is in dissonance and it is swiftly swept away by a gust of wind. As the neckerchief flies, we see that the piece of fabric has more freedom than Cathy, whose wardrobe and social position root her to the ground both physically and spiritually. When she follows the fluttering chiffon through her garden, she's following a siren call of freedom that will lead her to a life of new desires.

The key to that life is the son of her African-American gardener, a well of empathy that's at odds with every other person in Cathy's existence, be it her catty friends or the closeted neurosis of her gay husband. After that moment, we see the costumes gain a new dimension. They're no longer just metaphorical straight jackets, but barometers for Cathy's heart as she slowly starts standing out from the background. This is helped, ironically enough, by the old-fashioned nature of the character's style. Since Moore was pregnant during shooting, Powell had to design the costumes to conceal her actress's changing body. She did it with full skirts that are démodé when compared to the streamlining of 1957 fashions typified, in the movie, by Patricia Clarkson's social viper. Those opulent looks occupy a lot of space and their exuberance gains significance once Cathy starts bristling against her prison.

Their preponderance also calls attention to the few instances when the character wears something different from the norm. Initially, not only are her outfit's big, but they're also full of details that are almost too precious to not feel vaguely absurd. Bows are adorning the pockets of a fitted jacket, contrasting piping on Peter Pan collars, beaded lace, and scalloped hems. It all looks simultaneously matronly and infantilizing. On her last scene, though, after her husband has left, Cathy appears in a severe narrow-skirted suit. Her color scheme is still dominated by purples and reddish pinks, but there's a desire for change. What's horrifying and perfectly encapsulated by the costume, is that, while the men in her life may move on, Cathy can't. Even as her clothes lose their Barbie matchy-ness, they're still tied to the house's general color scheme, an umbilical cord that can't be severed. With costuming, Sandy Powell, the auteur, has created a heartbreaking tragedy that's as haunting as it is beautiful.

Gangs of New York is available to stream on HBO's many platforms, including HBO Max. As for Far from Heaven, you can find it on Starz and DirecTV. You can also rent both pictures from Amazon, Google Play, Apple iTunes, Youtube, and others.

Reader Comments (8)

The Academy chose Gangs of New York as their Powell nomination in 2002. That was a mistake. Yes, I'm certain "more" work went into Gangs of New York, with the further back period, longer movie and massive crowd shots. But...does anyone remember any individual COSTUME from Gangs of New York? The most memorable visual moment (as good as it is) has ZERO costume design in it. Meanwhile, I can point to multiple searingly iconic looks from Far From Heaven.

Everything she has done is wonderful. I do think her wins don't represent the highest achievements of her career. Her collab's with Haynes are stunning and in my opinion she should've won her three oscars for Velvet, Far From Heaven & Carol.

I will watching anything she works on because she does has a nack for great costuming. Not just for the women but she costumes men just as great which of course can be overrated in costume designing.

Thank you for this, Cláudio. I’m a big fan of Gangs of New York, especially for their costumes. Day-Lewis’ top hats and coats, the blue waistbands, and the spectacular dresses made for Cameron Diaz still impresses me among Powell’s best achievements. Far From Heaven, which I love too, I always thought as a more subtle work, and remember mostly for the great performances of Julianne Moore and Dennis Quaid.

" Far From Heaven" deserve to win every Oscar it was nominated for - its a modern classic

Volvagia -- Interestingly, when asked to pick one of her Scorsese looks for an exhibit, Powell chose an individual costume from Gangs of New York. I believe it was Bill's oxblood frockcoat number. I'm a bit biased because I'm a Powell obsessive, but I could probably draw you some Gangs of New York costumes from memory and I don't even like the movie al that much.

Eoin -- I agree that her Oscar victories aren't representative of her true genius. The Young Victoria's win seems particularly uninspired, even though I must praise the miraculous work that is to make 1840s fashions even mildly palatable to modern audiences. I think I'd give her Oscars for Orlando, Velvet Goldmine, The Aviator, Carol.

Antonio -- Overall, I prefer Far from Heaven, but I'm glad you enjoyed this piece. Revisiting Gangs of New York reminded me of how visually spectacular it is. I don't like the movie overall, but some of its individual elements are stellar, like Powell's work and Daniel Day-Lewis' arranged performance.

Jaragon -- I'd have certainly voted for it in Best Actress and Best Cinematography.

Interesting read,thankyou,I like FFH costumes more.

Oh, man. The Aviator had AMAZING costumes. And I should finally watch Gangs of New York.

Sandy Powell is the best costume designer in the industry and Far from heaven is one of her best works, those colors look so alive and fragile at the same time, for me is hard to choose when you have Chicago, but I slightly prefer Far from heaven (I love melodramas)