Gotham Nominees: "Faya Dayi"

Wednesday, November 24, 2021 at 4:00PM

Wednesday, November 24, 2021 at 4:00PM by Nick Taylor

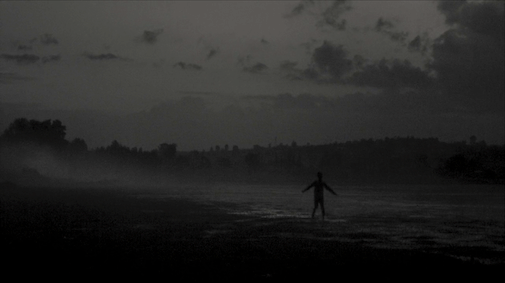

First thing’s first: Faya Dayi easily ranks as one of the most beautiful 2021 films I have seen. I don’t mean to equate its beauty with an automatic FYC for best cinematography, nor a backhanded comment on style over substance. In cahoots with the editing and sound design, the heavy, monochromatic images cloak Ethiopia in a hazy, dreamlike aura that’s foundational to the film’s tone and point of view, and unspeakably gorgeous to boot. I could've pulled a gallery's worth of screengrabs from the first five minutes alone. Producer/director Jessica Beshir also acts as her own cinematographer, and her ability to endow her images with such clarity and attention to movement, texture, and composition is a stunning achievement.

But is it fashion? Does the gorgeousness of the imagery actually serve the film, or is it too loaded down to carry its own weight? How much movie truly lies underneath all this black and silver? Well...

Faya Dayi takes place in the Ethiopian village of Harar, where Beshir grew up as a child. Her family fled the country when she was young, and in the time she was gone her village underwent a radical shift in which crops it produced. Originally renowned for their coffee plants, Harar now exclusively exports a stimulant plant called khat, which Ethiopian legend purports was prized by the Suli Imams as a way of connecting to eternity. The plant is now a cash crop sold across Ethiopia, and Harar’s economy is primarily (if not exclusively) based on harvesting khat, transporting it, and selling it to villages across the country. Faya Dayi is very much a showcase of how khat is harvested, and film’s style is meant to replicate the haze borne from being immersed in so much khat. But even more than that, Beshir’s camera is interested in weaving through the lives of the villagers who prepare it, depicting Harar as a town lost in the sauce of its endless khat supply.

Although the film has been classified as a documentary, the filmmaking gives it the feeling of a tone poem. Harar is more of a dreamscape than it ever is a physical location, one replete with older folks who long for the days of farming coffee and young people trying to handle khat-addicted relatives and hoping to leave Ethiopia altogether. Their testimonies are loosely scattered throughout the film, with a couple figures recurring through the film as they recount Harar’s history or debating getting passage to Egypt. I don’t know that Beshir gets away with how several scenes plainly read as restagings of earlier, off-camera conversations, but it fits Faya Dayi’s out-of-body tone better than a traditional documentary.

Still, the question remains: Is it fashion? Part of me suspects I might groove to Faya Dayi a bit better on rewatch simply by virtue of being acquainted with its peculiar style. Maybe it simply works best when the viewer is trapped in a theater. But I may also dive in again and emerge more frustrated with how Beshir’s style doesn’t really facilitate the sort of portraiture she’s aiming for. There isn’t much structure connecting one scene or testimony of Faya Dayi to the next, especially after the latest crop of khat has left Harar. I’d argue that folks who only appear for one or two scenes have the hardest time resonating, but even the people we return to throughout the film are too spread out for their stories to really land. The young man who wants to go to Egypt is present for a good number of scenes, but a specific plan to flee to Egypt that’s mentioned in his first scene doesn’t come up at any point until the very end of the film. Faya Dayi’s dreaminess has a hard time sustaining some of the more upsetting discussions people have about how their loved ones behave on khat. The heaviness of the cinematography ultimately makes the film as whole too impenetrable, even when it’s presenting a genuinely affecting story or striking image.

There’s also a problem with flow and pacing that, for my money, holds the film back even at its most promising points. Faya Dayi struggles completely with momentum, from the level of its overall structure down to individual edits, and I found it difficult to swing from so many jumps between a mood-focused montage to a one-on-one with someone we haven’t met before. It’s frankly surprising Beshir spends so much time reinforcing her dreamlike tone when it’s already so potent in even the most character- or information-focused passages. I expect if you’re in the film’s groove that its transitions and choices on what to focus on read as intuitive or surprising in a dream-logic sort of way, but it felt increasingly disjointed once it became clear that there wouldn’t be much to hold onto from one scene to the next except for the tone.

I admire a lot of Faya Dayi’s risks but spent a lot of my time with it thinking of Khalik Allah’s 2018 film Black Mother, an even more formally ingenious and narratively risky documentary that attempts to survey the past and present of a whole country, without striving for heterogeneity or being easy to sit with. That film gets away with telling about a hundred stories at once, all of which stand out on their own and still add up to a multifaceted presentation of Jamaica. Beshir could stand to let the many histories she presents breathe on their own terms. There is every chance you might get more out of this than I did. I might even get more of this on a second watch than I did now. But I mostly feel as though Faya Dayi has a lot of fascinating, worthwhile stories that its incredible lensing ultimately smothered a bit. The gains in mood and atmosphere richly convey a very real, very sad idea about Harar’s trajectory, but the inability to bring out the stories of the people living in the city’s fog prevents the film from really becoming something special.

Cinematography,

Cinematography,  Faya Dayi,

Faya Dayi,  Gotham Awards,

Gotham Awards,  Reviews

Reviews

Reader Comments (1)

Dear Mr. Taylor,

You set the tone of your review of Faya Dayi with this phrase, in the first paragraph:

"In cahoots with the editing and sound design, the heavy monochromatic images cloak Ethiopia in a hazy, dreamlike aura that's foundational to the film's tone and point of view."

And in the following paragraph, you ask:

"Does the gorgeousness of the imagery actually serve the film, or is it too loaded down to carry its own weight? How much movie truly lies underneath all this black and silver? Well..."

I believe you are asking about form and content, the perennial choice that all artists must make with their work, and which they must decide takes precedence, or whether to weigh them both equally.

Beshir chose form over content. Or more precisely, she chose to camouflage content with form.

The "hazy, dreamlike aura" hides this content, which you adroitly describe: "There isn't much structure connecting one scene or testimony of Faya Dayi to the next..." And "...Beshir's style doesn't really facilitate the sort of portraiture she's aiming for..."

Beshir uses khat as a subject, a protagonist, that leads and guides the direction of the film, but whose "haze" hides the truth of these Oromo youth. For example, the young man who wants to go to Egypt has no game plan, and khat becomes his crutch, his "co-actor," as the drug he takes to avoid the reality, the content, of his life.

And Beshir also uses this khat as a stylistic, cinematic metaphor, to hide from us, the viewers, the content and reality behind her film. She films as though she herself is under the chewable spell of this drug, and it is likely that she took khat as part of her filming process.

Khat causes devastation, but it also produces the spiritual Sufi high, and it provided her (literally, possibly, but certainly cinematically) the form with which she can shoot and produce this film, whose main protagonist, as I said earlier is khat, but perhaps khat's merkhanna might be more precise.

She cannot full-on discuss the devastation that the khat crop produces for this Harari-Oromo Ethiopians, since khat is after all part of the merkhanna, the spiritual high, that is sought after by the regional Sufi-Harari Muslims. This film should have centred directly on this agricultural devastation, rather than weave through "spirituality" and mekhanna, through khat.

Khat thus becomes the distinguishing object, the"Sufiness," and the merkhanna upon which this film rests it laurels.

But what is Beshir hiding, what is she camouflaging?

Of course, more directly, it it the devastating, life-destroying drug that has become the life of these Harari-Oromo youth.

But Beshir is also projecting a political angle, and a strong one. The Harari-Oromo youth, through oppression, governmental neglect, and poverty, are forced to give up other cash crops like coffee in order to grow this substance for their livelihood, and their energy-inducing chanting calls (mimicking religious chants) gives them the rhythmic, and spell-binding, strength to harvest their currency.

And of course, through the haze of her cinematography, it is not clear which government, which export route, and what kind of neglect.

Once Beshir starts to clearly answer, or present, these issues, then her khat thesis of the oppressed, neglected, and devastated Oromo youth falls apart.

Beshir is talking about the governments previous to this one, whose current leader is Abiy Ahmed Ali, a 2020 Nobel Peace Prize winner, whose father is Oromo-Muslim (and mother an Orthodox Christian Amhara - and he himself grew up a Christian, and married an Amhara Christian wife), and who was born in the Jimma region of the Oromo province.

Previous to PM Abiy Amhed Ali, Ethiopia was run by two successive, vicious, Marxist governments. The first was installed after massacres of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian, of all ethnicities, as the Emperor Haile Selassie, the emperor who stood his ground against fascist Mussolini's invasion, was deposed in the early 1970s. Decades of rule under Mengistu Haile Mariam, the Communist head of state of Ethiopia until he was removed by another group of hard-core Marxists in 1991. This second group also spared no lives to further their totalitarian regime.

PM Abiy was a young man when he became an officer and joined forces to oust this second regime. He eventually went on to become a re-elected leader of Ethiopia (Ethiopian elections were completed just last year).

During both these eras of Communist rule, through manufactured famines, mass executions, perpetual states of emergency, and innumerable non-trial arrests, Ethiopians still endured. But, these totalitarians saved no person, had mercy on no-one. Oromo, Amhara, Tigray, and a host of smaller ethnic groups received the same harsh treatment under the self-installed "judicial" system of these post-Haile Selassie, and pre-Abiy Ahmed, leaders.

This is the back story Beshir's camera cannot tell you, which Beshir will not tell you.

She theretofore picks up a pet project - khat - which she remembers her grandmother harvesting in her garden as she practiced her Sufi incantations - and projects it into the lives of these Oromo youth, upon whose poverty, and whose backs, she builds her cinematographically hazy images, from her smart, Brooklyn apartment, gathering monies and grants from a host of "sympathetic" agencies, and screening her films in art-house film festivals, who profess support for oppressed peoples of the world, in the pop-corn outfitted theatres, in air-conditions auditoriums.

And, here is, I believe, her end goal. Her film, and her picking at these sores and frustrations, could instigate enough anger in her "oppressed" Oromo youth, that they may be ready to pick up whatever sticks, stones and few gunpowder, to start their own "revolution" for "freedom." And these Western audiences would shower their support, their concern, and their editorial opinions. Faya Dayi becomes/is a reference manual.

Beshir is evasively active in numerous Oromo liberation groups - through Facebook, Twitter, and through her meetings/screenings of her film Faya Dayi, and other films she's done to date, namely one titled Hariat on the hyena in Harar, in the US and now in Canada. She will never openly present this, since there would be too much negative reaction, especially from her funders, and especially from her viewing public.

Her film gives her some validity in the eyes of those who publicly pronounce this liberation movement, and acts as a documented reference for future activities, and actions. They can cut through the form in Faya Dayi, and get at its content.

One other thing Beshir won't dwell upon is her use of "Ethiopian" as she describes her identity. She calls herself Mexican-Ethiopian.

She shows no love for Ethiopia, and uses that word opportunistically, as she uses those devastated youth of Harar, to gain access into world view, and to be recognized (and noticed). Mexican-Oromo doesn't cut it.

And if she were really sincere, she would simply call herself "Oromo" and return to the land which she left as a teen-ager, and make amends. Opening up a drug rehabilitation centre would be one way. And PM Abiy, through his Ethiopian First commitment, has already started khat-rehabilitation projects for these youth. Beshir already has the place to go, where her Faya Dayi prize money might stand a chance.

I will be watching her next subversive, elusive, moves, as I suggest you do too.

I commend you for understanding the elusive nature of this documentary.

Sincerely,

Kidist Paulos Asrat

Art and Commentary by Kidist Paulos Asrat

https://artandcommentarybykidist.blogspot.com/p/ethiopias-elections-strong-and-united.html