Review: "Mami Wata" Brings West African Folklore to the Big Screen

Friday, September 29, 2023 at 9:30PM

Friday, September 29, 2023 at 9:30PM

As if dipped in ink, the screen is a void, shadows so thick they seem to swallow the light. Gravity-pulling like a black hole, this emptiness must be broken. So, it is with water leading the way, that eternal life-giver, life-taker. And even before we see its tide, we feel an ocean calling. It emerges in white lines, foam on cresting waves, their back-and-forth movement an Atlantic embrace. No character has invoked her yet, but we already sense the immensity of Mami Wata, the mother-like water deity that appears across African myth and the diaspora. In a feat of miraculous cinema, Nigerian director C.J. 'Fiery' Obasi has used his third feature to summon the spirit, inviting us to commune with her.

That's not to say Mami Wata – now in theaters – is a film aiming solely at religious ecstasy. If possible, it has even greater ambitions. Its tale is the story of a matriarchal society threatened by patriarchy and treacherous progress, of a sisterhood trying to resolve ancient contradictions while preserving the old ways into a changing world…

The fictional town of Iyi, on the West African shore, feels like a place existing out of time, our present modernity kept beyond borders by a tradition-minded community. Though the figure of Mami Wata has become taboo in contemporary Nigeria, her cult decried as demonic by Christianity and Islam, director Obasi imagines, here, a people who still hold faithful to her divinity. Indeed, the highest figure in the social system of Iyi is the Intermediary between the water spirit and humankind. She's Mama Efe, an elder whose word is sacred and whose way of life is sustained by the peoples' offerings.

It doesn't take long for fault lines to crack across this fragile idyll, the Intermediary's jurisdiction under pressure by forces from within and without her own household. Even Mama Efe's adopted daughter, Zinwe, and faithful protégé, Prisca, are starting to question her unbending rule. The situation is complicated by the Intermediary's failure to channel Mami Wata's grace and save a sick child's life. When mutinous villagers accuse the old woman of wrongdoing, saying the boy should have been taken to the hospital, it's difficult to fault their outrage. Zinwe, in particular, can't understand her mother's resistance to modern medicine.

But maybe Mama Efe sees what the youth cannot, how the intrusion of Western values and their ideas of societal advancement could lead to the collapse of Idy as they know it. The insurrecting Jabi may speak of schools and medical aid, electricity and good roads, but is that what will come to the village if he has his way? Moreover, is that what his faction really wants, or is progress a subterfuge for power-grabbing? When a mysterious man washes ashore, the tensions rise further, his ambiguous intentions proving poisonous in no time. Together with Jabi's men, the stranger called Jasper comes to personify all the vices of our modern times, and none of the good.

Mami Wata's central conflict shines a light on the age-old tensions confronted by many African cultures, pursuing an ideal of 'balance and harmony' that reconciles past, present, future, pre-colonial tradition with post-colonial realities. The narrative further contrasts the imperfections inherent to both matriarchal and patriarchal regimes, finding that the latter ultimately brings nothing but destruction. This is all present in a style not too far removed from declamation, a strike of old-school pageantry that may alienate some viewers but feels consistent with Obasi's vision of a cinema deferent to folkloric practice.

Not all actors thrive in such stylistic constraints, but Evelyne Ily Juhen has a firm grasp on the picture, tackling her role with such confidence that one can't help but stand back in awe. Her Prisca is Mami Wata's grounding element par excellence, keeping the narrative from detaching too much from recognizable reaction. She further sketches an arc that can survive the film's odd structuring, owing much to chaptered tales and the advent of silent movie intertitles. Even with a story broken into truncated episodes, Juhen lets us experience Prisca's predicament, from a crisis of faith to the shock of betrayal, revolt, resistance.

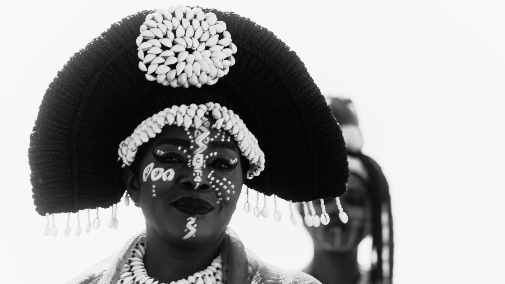

Finally, one can't talk about Mami Wata without extolling the wonders of its look. Simply put, there's nothing else like this film in theaters, its visual idioms so distinct they seem to propose an African cinema wholly detached from Eurocentric paradigms, give or take some love for the graphicness of Expressionism. As shot by Afro-Brazilian DP Lílis Soares, the Folktale is a high-contrast dream of monochrome photography, lit with theatrical gusto and designed for maximum boldness. The black shadow is often so deep one sinks into spatial ambiguity, while the villagers' white-lined faces and cowrie shells shine, almost iridescent, in the night sky. By daytime, the magic remains as the digital image is pushed to the limits of otherworldly beauty.

It's a conflagration of mesmerizing sights that rightfully won Soares a Cinematography prize at Sundance and makes Mami Wata essential viewing for all those who care about film.