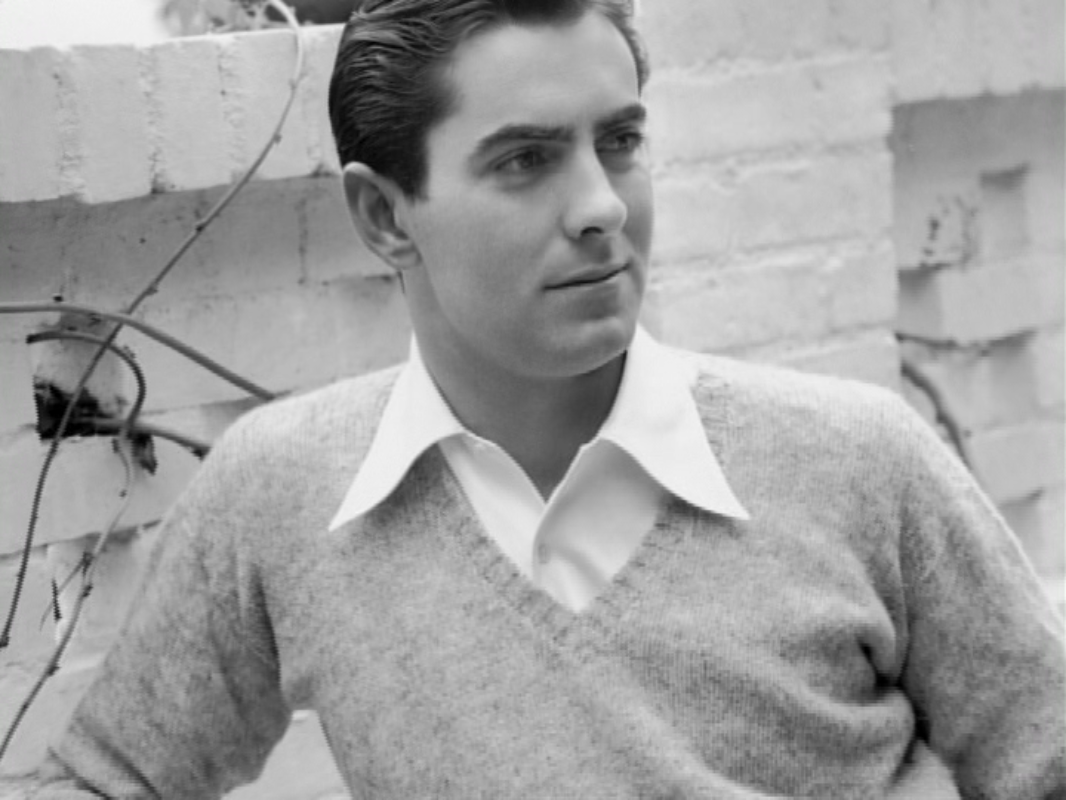

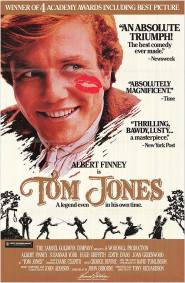

Andrew here to celebrate an anniversary. Fifty years ago tomorrow, Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones won the 1963 Best Picture Oscar at the 36th Academy Awards. Up until a few weeks ago it was one of my most glaring cinematic blindspots from that era.

Andrew here to celebrate an anniversary. Fifty years ago tomorrow, Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones won the 1963 Best Picture Oscar at the 36th Academy Awards. Up until a few weeks ago it was one of my most glaring cinematic blindspots from that era.

A cursory glance over the Best Picture winners of the 60s (ha, who am I kidding? I know the list by heart) reveals that by my faulty empirical research Tom Jones is easily the least discussed Picture winner from that decade today. Even Oliver, arguably the decade's least respected winner, seems more oft considered and it’s a curious thing because even ignoring the actual quality of Tom Jones it’s not business as usual as far as Oscar winners go. And, usually, we like to talk about when AMPAS throws us a curveball with its winners, for better or for worse.

Certainly, from an outsider's perspective it doesn't seem to be much of a curveball. What's the fuss about another period-piece turned Oscar winner? Although period films are lucky with awards they don't tend to be well remembered, or loved, on the internet. I could imagine what Tom Jones seems to represent to someone on the outisde looking in, another stuffy British drama Oscar bait film. (Something's that plagued Merchant Ivory films two decades after their heyday, but that's another story.) But, Tom Jones in all its unusualness has much to savour and enjoy, fifty years after its release.

Here are ten reasons to give it another or your first look...

Click to read more ...

Monday, May 5, 2014 at 12:01PM

Monday, May 5, 2014 at 12:01PM