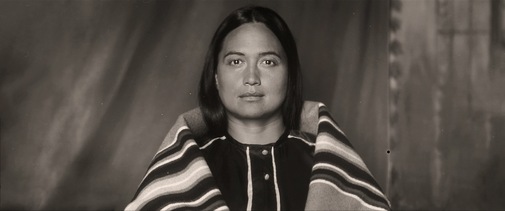

On Gladstone and Scorsese's Mollie Kyle

Thursday, January 11, 2024 at 6:00PM

Thursday, January 11, 2024 at 6:00PM Oscar voting opens today, and, for once, some of my favorites are poised to thrive on the nomination ballot. Because of that, it might seem overkill to write FYC pieces, those love letters by another name. Even so, as it's a time for advocacy, I shall articulate why some of the year's best cinematic achievements deserve to be recognized as such. Today, I find myself inspired to make the case for Lily Gladstone, a virtual lock for a Best Actress nomination who might win it all. And to think some said going lead would ruin her Oscar hopes.

As Mollie Kyle in Martin Scorsese's Killers of the Flower Moon, she breathes life into a dark chapter of American history. Gladstone illuminates the tragedy of a woman and people betrayed, forsaken by individuals who claimed to love them and systems who exploited them under the guise of protection, brutalized by greed and white supremacy…

Before Killers of the Flower Moon ever reaches the tale of Mollie Kyle, a history of cultural schisms and great sorrow has already been established. Perhaps more important to the matters of performance cum character study, it reaches Fairfax, Osage County, through the foot of Ernest Burkhart sometime in the aftermath of World War I. The real-life figure had established himself in town years before enlisting, but Scorsese and co-screenwriter Eric Roth adapt fact to better suit their dramatic intent. Returned from service under military authority, Ernest is quick to fall into another such system of renounced responsibility with his uncle, William Hale, the self-proclaimed King of the Osage Hills.

Despite this trick of structuring befitting the film's trickster noir aspirations, Scorsese made sure his audience met the Osage people before their wealth and before this fool is lectured on them by an autocratic relative. In doing so, the viewer is even more predisposed to notice how the older man presents his information. He describes them as "sickly people. Kind-hearted people, but sickly people." Words dripping with condescension, he projects false grandfatherly affection by repudiating prejudicial dismissals of their character. "The Osage are sharp. They don't talk much (…) Just because they're not talking don't mean they don't know everything about everything." It's a sprinkling of sugar to mask the taste of poisoned gin.

And yet, this warning regarding silence is a fair point. In the book on which the film is based, David Grann mentions how white people were prone to interpreting Native people's taciturn nature as a sign of dumbness, mayhap even soullessness. They used it as another tool in rationalizing hate, justifying their prejudice and its dehumanizing conclusions. So, while we might want to turn away from everything Hale says, the Devil sometimes speaks truth as part of his ploy. Certainly, we shouldn't take on the Osage silence as a sign of inferiority. In Scorsese's late cinema, silence is a multifaceted idea that can be as terrifying as it is ennobling.

Indeed, when adapting Shūsaku Endō's Silence, the director would have done well to remember its value. In that production, narration is a constant, verbalizing what the actor's wordless work had already telegraphed.

This redundancy remains my greatest issue with a film I otherwise love, so I feared a repeat of it going into Killers of the Flower Moon. But Scorsese has chosen a different approach. Hale and Ernest reveal who they are in their lies and half-truths, quickly talking themselves into a corner of the audience's moral judgment. On the other hand, Mollie is permitted to exist in her silence without needing to have everything inside her explained through text. In a beautiful beat of paradoxical filmmaking, this doesn't preclude Gladstone from talking over the moving image. When we finally meet Mollie, she's speaking to us in voice-over narration, a privilege no other character gets.

While there's great depth in silence, I can't complain about being introduced to Gladstone through one of her key weapons as a performer – that melodious, measured voice of hers. Hearing it now, so directly, will make its progressive absence all the more intolerable. But what about what's said? She delineates the fate of her people over tableaux of death, the brutality of killing contrasted with the victim's repose under funeral rite. At times, we even glimpse the murder happen as she declares the case shut by authorities and deemed suicide. There's such exhaustion in the sound of her telling, a bone-deep sorrow in every syllable. It's like a slap when her entrance leads to "I'm Mollie Kyle, incompetent."

It's the first line she speaks within the film's reality, engaging another person rather than the camera and the audience beyond. The language is blunt, an act of self-humiliation demanded by the powers that be, a formality in the racist system she inhabits. However, though the act is denigrating, both Mollie and Gladstone keep their dignity. It's a powerful introduction that beseeches the viewer to read into the words unspoken, the poise and passive resistance of Mollie. Notice how she swallows any objection against the man who's got her fortune under his thumb. At the end, there's a suggestion of a smile, some placid performance of acquiescence that'll put the white authority at ease.

To him, it corroborates her incompetence and childlike helplessness. To us, it's a knowing, unknowing smile, a façade of serenity that's more strategic retreat than capitulation. Even more than her oft-silent and silenced words, Mollie's smiles are a precious commodity within Killers of the Flower Moon and help erect the arc of her undoing, resistance, survival. Early in the picture, they're more common, even if not always sincere. She seems honestly content at Osage ceremonies, but those grow fewer and far between as the Native population is violently cut, their customs gradually receding into the background, unseen. Even when her sickness worsens, Mollie still smiles in Osage ceremony and Christian church.

Her genuine smiles reach her eyes. Her polite ones never do. It's a distinction that becomes obvious when, after that bit of painful bureaucracy, the viewer gleans the first meeting between Mollie and Ernest, working as her cabbie. She doesn't take his offered hand getting into the vehicle as she'll later do, a sign of early reticence when dealing with this white man, new in town and thirsty for riches. But as the ride continues and more rides come after, she relaxes, perchance amused by Ernest's dimwitted openness and bad jokes. Whether it's a smirk in the rearview mirror or a face-to-face grin, Mollie is gratified by the man's presence. What he looks like to us is immaterial as long as Gladstone can convey the layers of attraction falling into infatuation.

He's simple and boyish, flat-footed clumsy, so open about his mercenary intent that the unsubtlety tastes like accidental honesty. Even if the viewer can't appreciate it, she sure can. He counterpoises the innate seriousness of the responsible daughter we'll know her to be, the put-upon sister who's stalwart and believes diabetes will take her before her time. Furthermore, Ernest's dimwitted blasé nature almost seems to give her security. She's smarter than this lazy man whose lack of substance will mean he's not as likely to run around or walk over her. Or so the movie's Mollie would think. The character flaws that make him an agreeable partner are central to his evil. So, though her smile is knowing again, in the broader context, she doesn't know what she's getting herself into.

From the car to church and back again, to her house, where they have a first date of sorts. I'll be honest: this after-dinner sequence is my favorite passage of Killers of the Flower Moon, maybe of the entire cinematic year, culminating in a demand for quiet while the sounds of nature clamor over the smallness of Man. But there's more to it, such as the ways in which their interaction develops the chemistry that arose in their car-riding scenes. And new depths come forth. Please pay attention to a hint of resentment in Mollie's expression when mentioning her mother. It's nothing but a side-eye, just a slight movement, a touch of anger to be echoed later when facing the older woman's displeasure. The actress fleshes out a personal history beyond the film's narrative, expanding under its frame.

Though saturnine, Mollie reveals much about herself in a conversation that, on paper, might feel like a two-sided interrogation. But Gladstone plays it like a candid negotiation of intimacies with a potential beau. As a performer, she's excellent at acting attraction and fondness, suggesting the depth of emotion the text eludes. In my eyes, it's not a script deficiency but rather a trust in the actress. Through Gladstone, we see Mollie letting him in, little by little. And there's yet another reality making itself known on the margins of these scenes - she likes to be wanted. More specifically, she likes to be wanted by a white man and all that promises. Kissing in the car, she'll contemplate how his pale hand looks over her darker skin, and Gladstone lets a note of wonder intrude upon Mollie's sensible voice. If there's a facet of fetishization to his desire, she lives with it in a most familiar compromise.

The scene of the sisters talking about their men after church is another crucial moment of lightness before the shadows close in and snuff all that's joyful out for good. It tells us what we need to know about Mollie's complicated feelings for Ernest at the onset of their romance. This time, it's not something to be gleaned from performance notes and context clues – it's plainly stated in the text. She likes his blue eyes and finds him handsome, even as the sisters disagree and see more beauty in his brother. Sure, Mollie recognizes his mercenary wants, his desire for money, but she appreciates his supposed need to settle. She sees him as a coyote she can tame or live with regardless. It's the pragmatism in her. It's the naivete. These are confidences shared between sisters in the Osage tongue, laughs and gentle teasing lacing their communion with warmth and familiarity.

When death comes knocking, the memory of that temporary happiness will be lemon juice poured over an open wound.

First goes Mollie's sister, Minnie, and Gladstone refuses to underplay grief. She cries, shouts, and breaks apart, sharing the pain across the camera and the screen. Then, Anna is dead – killed – and seeing her body, Gladstone conveys Mollie's horror as near catatonic. There's the idea she's going to throw up, but the actress plays the sickness like something kept barely under control. As an autopsy out of one's worst nightmares gradually manifests, Gladstone disconnects Mollie from what's happening. At the height of affliction, she covers her ears and rocks, a traumatized woman trying to lull herself into an impossible peace.

In a new confession to the viewer, Gladstone's voice speaks of an anger consistently sublimated in stares and the tension of maintaining composure. Throughout tribal council and attorney talks, Scorsese and Schoonmaker keep cutting back to the actress' face as other characters talk over Mollie, examining the visage of one who's losing everything. "This evil around my heart comes out of my eyes," she says, and we can see it plainly. She's a body wrecked by sickness, a spirit consumed by paranoia, and in this nightmare of an existence, Ernest becomes her support. It's a horrifying reality, but that ugliness doesn't make it any less accurate. The filmmakers don't overexplain, they let you absorb the treacherous emotional web of the characters and make your conclusions.

Part of it is an admittance of our limitations when looking at history. We have records of Mollie and Ernest's relationship, but the truth of their hearts will always be unreachable. The film lets us get close while denying the arrogance of presuming to expose all of their mysteries. And yet, how could we be closer to the film characters than in the secrecy of their bedroom, watching how the husband assuages his wife's pain with sweet lies and untruths he might think true? Right after questioning the man's love, Mollie will smile and allow herself to get pulled into an erotic embrace. Fueled by the actors' chemistry, this portrait of spousal harmony is both affecting and infuriating, for it looks like love but surely can't be. Let that thought eat you from the inside out.

At this point, smiles have become rare to the point one questions if they're really there whenever the camera catches them. At the doctor's office, for instance, Gladstone is a bottomless pit of caution when talking to the medicine men, only ever trading in softer expressions with Ernest or their children. The actors establish different levels of trust as if building a house of cards to be brought down most terribly when Mollie finally accepts the misplacement of her heart. But there's a long way to go until then. The first suspicion explodes in the only argument we get to see between the married couple, when a weakened Mollie tries to reject the doctors' insulin injections. Mostly verbalized in un-subtitled Osage, we don't need the words to understand the rhapsody of doubt and fear roaring between the actors.

Scorsese trusts you to pay attention to her tone and face because her ultimate, wordless resignation is where the cinematic "truth" lies. She must believe Ernest when he proclaims his love, that the medicine is for her health, that he'd never hurt her. What else can she believe? That she's powerless and her whole life's a lie? That she let herself live with the murderer of her kin? Like a displaced preamble to Mollie's last scene, Scorsese and Gladstone invoke the possibility of guilty feelings beyond Ernest's conscience. Part of her ultimate acceptance, taking the injection like her husband wants, is also a consequence of exhaustion. At a certain point, one grows tired of fighting. Better to give in than keep speaking up for oneself and suffer just the same.

It's easier to capitulate than inspire hatred in the only person still there for you, loving you. There's a movie's worth of marriage stories happening in one scene, a tale of conflicting self-delusions and despair in the face of abuse. Now, I know I am bringing a lot to the proceedings as someone who read the book beforehand, got intrigued by Mollie Kyle's story, and has a personal history that might echo through portrayals of toxic relationships. However, I also believe one must credit the artists at hand for inspiring such reflection. Despite what others have criticized about the film's decentralizing of Mollie, scenes like this make a thousand thoughts rattle in my head and feel, if only for a moment, that I got Mollie or at least Gladstone and Scorsese's version of her.

Outside the chamber drama, death keeps coming, and with each funeral, a part of Mollie erodes away. Rather than play an anesthetized stupor, Gladstone continues to let grief affect the character in ever-growing waves. Each new loss is a crack in the foundation of her personhood, her poise. Even the ghost of a demise yet to happen seems to sneak up on Mollie. It's the unspoken tension Gladstone exudes in the presence of William Belleau's Henry Roan, a childhood fiancé according to Osage tradition. When news of his demise reaches her, there's no surprise or shocked reaction. Instead, there's a pause, a question - "Was he murdered, or did he kill himself?" Tears come first, but they dry quick, but the proffered doubt lingers. The sound of her words may not reverberate on the soundtrack, but it sure does inside the viewer's head.

As does the scream she lets out when Mollie's final sister dies in an explosion. While the camera keeps its distance, Gladstone wails and crumbles, as if daring us to look away or cover our ears. It's sorrow and it's fury, tangled up and aflame, doused in gasoline for good measure. Maybe because this scene is so lacerating, Scorsese lent his version of Mollie a shred more agency than the real woman had in life. Her trip to Washington to appeal to the government for federal intervention in the Reign of Terror is fictitious. However, it lets us consider Gladstone's characterization at the height of despair but still active enough to take action. As the poisoned insulin takes its toll in the following hour of film, we'll fondly remember a time when Mollie could do such a thing.

At church, proclaiming she's afraid of being in her own home, Mollie almost looks lost in some somnambulistic daze. Gladstone contains a horror film within Killers of the Flower Moon. This could be an Ethel Barrymore situation with all the stodginess that entails but instead reads like an existential apocalypse, visceral to the nth degree. You have to admire the complete surrender of Gladstone to Mollie's physical decline; the corrosive nature of Ernest's love manifest in undeniable visual terms. It's sweaty and disjointed, far from notions of idealized martyrdom. One could expect another conclusion from the Catholic mind of Martin Scorsese but, just like in Silence, Because, we're made to see there's no inherent nobility or spiritual valor to suffering. It's pain and pain alone.

On the brink of death, Mollie's rescued by the FBI men after Ernest's arrest, and we see glimpses of her recovery, lost in the flurry of montage. From the physicality of someone learning to walk again to a supervised reunion with her husband on a field, the woman's marital trust starts to seem obscene. In any regard, it's upsetting to witness, and one begins to search for clues of wariness in Gladstone's portrayal. They can mostly be spotted by comparison, by weighing her tone in scenes past, such as when Mollie asked Ernest if he feared his uncle during their dinner date. Now, when she asks similar questions, a new keenness emerges, her stare more doubtful, eye contact wavering slightly. These are the dying embers of trust. Watch them die when Ernest Burkhart finally admits to his crimes on the stand.

Throughout the film, Scorsese and Schoonmaker have used Gladstone's muted reactions as a central factor in the film's storytelling strategy. At points, those reactions gained another value as one came to sense certain moments as manifestations of Mollie's perspective. Take the wandering camera peering at white people's faces at the train station and during baptism, paranoia given film form. Take the fiery interlude that comes across like a Witch's Sabbath, hell on earth as envisioned by the Christian imagination. And here we must remember that Mollie, not Ernest or Hale, is the one whose spirituality is more in tune with the camera both because of her Osage tradition and Catholic faith.

At the final trial scenes, the image cuts to Mollie at precise points, confronting us with her own confrontations – not just with the culprit, but with the facts, with her ignorance of what was happening. The flashbacks to Anna's death are as much the killer's mind as Mollie's imagination, harrowingly couched in the image of her gently putting a pillow under the killer's head. Then, her eyes are fixed on him during Ernest's second testimony. Even when the prosecutor brings the jury's attention to Hale, the cutaway to Mollie reveals her eyes never leave Ernest on the stand. Judgment, hope crumbling, love rotting away within her steely gaze beneath a shroud of unshed tears. She only ever wavers when he proclaims his love. Gladstone's Mollie can't stand to stare at that love anymore.

Thus, we come to Mollie Kyle's last scene in Killers of the Flower Moon, a culmination of Lily Gladstone's performance and final testament to her shattering achievement. For me, it's sublime.

Entering the room, Scorsese's lens observes us as it tends to do. She's the most beautiful person in existence. She's the Virgin Mary in Osage blankets. Her words cut through his panicked babbling like a hot knife, sizzling as Mollie reminds Ernest of their daughter when he only asks about their white-passing son. Instead of steeliness, Gladstone works within a register that's almost too soft for comfort, a despondent exhaustion that's never been so pronounced, not even near death's door. Something broke inside Mollie, and it's dolorous to hear, to see, to experience. Hers is a symphony played in minor key, reaching the most desperate coda as Mollie asks her husband if he has been poisoning her with the injections.

This, right here, is the final destruction of their bond, so central to Killers of the Flower Moon. It's not Mollie giving him a chance at redemption, though. It's Mollie coming to grips with the reality of his hollow love, that this is a man for whom nothing's sacred, and what that means to her as a devout Catholic whose feelings on guilt and blame, on salvation, are shared by many of Scorsese's heroes and lost souls. Ernest's denial is worse than his admission. It takes away the possibility of truth to their supposed union, because it spits in the face of their vows, their devotion sworn under two faiths. As an epic draws to its close, Mollie is the last person standing and wrestling within themselves, for she's the only one capable of examining one's soul and existing within the silence.

Lily Gladstone keeps it inside, a storm of disappointment suggested by her gaze and little else. Serenity prevails, even if only on the faintest of surfaces. Her physicality is as quiet as her symphony, minor-key and stately, still haunting despite it all. And in memory, her performance shall remain colossal, a cathedral.

Disdainfully looked down by the camera and the woman he swore to love, Ernest is left alone, and Mollie exits stage left. There's no absolution, only a dark tale to tell and imperfectly share, to reckon with for perpetuity.

In this exhaustive analysis, I hope to have explained what makes me love Lily Gladstone's portrayal of Mollie Kyle so much. Moreover, I hope you glean how that portrayal is constructed not just by the actress' work but by a whole network of textual and directorial decisions, precise cutting, and framing. I believe that, though many writers I admire think otherwise, Mollie Kyle in Killers of the Flower Moon is one of the year's best and most fascinating creations. Honoring the historical person is a responsibility so great as to be unreachable, and Gladstone, Scorsese, and all others did an admirable job. At the very least, they created great cinema. Feel free to disagree, but I must remain faithful to this truth of my own.

Reader Comments (22)

This is such a thorough write up I want to watch just her bits again,I was impressed though I don't think it ranks up their with classic performances but maybe in future years it will.

I have Lily at no 3 on my own ballot behind my no 1 Teyana Taylor and Carey Mulligan 2nd with Natalie Portman in May December and Michelle Williams in Showing Up 4th and 5th,I've not seen Stone,Huller,Chastain or Barrino.

I am so intrigued by Lily and what her performance holds, but I cannot stomach the idea of a nearly four hour movie of this depressing nature with only her performance holding my interest. I am still rooting for her Oscar win, though. She's a fantastic actress.

I can’t revisit another 3 1/2 hours watching this movie again. Good luck, Lily.

Good article, Alves.

Very well written and full of love for your subject.

Gladstone is excellent. Her presence - and also DeNiro - is the best thing in KOTFM.

Nevertheless, I think it was a great risk promote her as leading.

It's a very strpng year. We have a sparkling Mulligan, a powerful Stone in a tour de force performance and a remarkable and overdue Bening.

Considering Gladstone in that thin line between leading and supporting, I think she can be pretered - except for the power of narrative, what I think is not fair.

This is beautifully written, Cláudio. You have articulated why her performance works wonders and is key to the success of KOTFM.

I will never forget watching this in opening week in the cinema, with Gladstone's face projected onto the big screen, with such serenity and yet depth and complexity that is beyond comprehension to me. I think it's terrifying being called the "heart and soul of the film" simply due to the hyperbole it might invoke, but Gladstone truly is that anchor that gives the film the emotional heft that it needs.

Rewatching KOTFM might be a daunting task given its downbeat tempo (which is a brilliant choice by Scorsese and Schoonmaker, btw), but Gladstone is and will always be the one thing that I hold onto and gets me through this film. Having said that, I will never get behind anyone who calls this performance expressionless or does nothing.

And no, it's not a difficult question for me: she is a lead in the film and is rightfully campaigned as such.

She's fine.

Great and meticulous analysis. You remembered me why I loved so much this movie before the boring awards season started. The use of the silence that you depicted make me think to what Scorsese did with Anna Paquin character in The Irishman

I personally feel that the narrative has taken over the performance which is very solid grounded moving and real but it's not the best of the year for me.

Peggy Sue though i'm not on the Gladstone winning train I do think she's more than fine.

I'd put 2 actresses before her Carey Mulligan and Teyana Taylor who could have used some of that campaigning Andrea Riseborough got last year.

With the right focus on her campaign she could have followed Halle Berry and been crowned a winner.

It's a good performance that elevates an underwritten part, but it's still not worthy of winning. Stone, especially, but also Hüller and Mulligan deliver better acting performances. So does Teyana Taylor, who will, unfortunately, not be nominated.

@Peggy Sue: I hate that you condensed this well written analysis down to that…but also you’re right so I can’t argue with you.

Claudio, as always, a very thoughtful and insightful essay! I do think Gladstone is superb in the movie, but like Ad_Mil and some other folks, I don't think it's worthy of winning. The character is just so passive, and early on, we see that the whole family is just going to be taken down, and then all we have is THREE HOURS while it happens. Gladstone fills in all the blanks, and the part couldn't be played better, but the character lacks dimension, and there's only so much she can do.

I'm rooting for Emma to get number two, or Sandra Huller. Their acting is so dynamic and exciting, and has so many layers and jagged edges...Gladstone is a little too controlled for a little too long.

If she's passive AND excellent in the film, then she deserves to win. Nothing wrong with playing passive excellently. In my opinion, her role wasn't that difficult and the performance not that outstanding.

I wish I saw all of this in the performance but what I see is a very good actress with a cliche stereotypical role --it's like the 2023 version of what people now deride about early big-deal dramatic roles for black actors: Noble Suffering. I think she's very good in the two passages you spend a lot of time with (the date and the conversation with her sister) but halfway through the film Scorsese becomes way more interested in the people he's always interested in (DiCaprio and DeNiro) and the film's inability to really stick with the Osage people is a real bummer. Plus I never bought Mollie's love for Ernest which for me is less her fault (she really does show the sexual attraction) and more the fault of Scorsese and DiCaprio and DeNiro, who are all doubling down so hard on OBVIOUS villany that it has the unfortunate effect of making Mollie and the Osage community at large look stupid rather than duped, even though Gladstone projects intelligence as an actress.

In short the film is constantly working against her! think she's good despite the problems with the film but Ive seen at least a dozen actresses this year that had more exciting or equally demanding roles and did them justice!

I can't say I'm surprised at the response, but still a bit disappointed. Either way, one can't expect agreement from everyone in matters as essentially subjective as art. I want to thank you all for reading this very long piece and giving it a chance, even if you disagree with its conclusions. Also, Mr Ripley79, I completely agree that Taylor is among the year's best performances.

However, I would like to leave a few stray thoughts.

Mollie Kyle was a real person, she did stay with Ernest through the Reign of Terror and believed him to be blameless even when she was already at the hospital and he had confessed to the FBI. Barring a few adaptations - Ernest's arrival in the community, Mollie's trip to Washington, the ages of characters - the script is fairly accurate to historical fact. I think there's a responsibility to reality when tackling stories like this, and making Mollie much more "active" to meet modern expectations of behavior and self-advocacy would have been a betrayal to her memory. I understand the desire to see Ernest through her eyes and be seduced as well, but that, to me, isn't the point of the film and shouldn't be a requirement to empathize with the characters on-screen.

I also think this film shows the banality of evil, so many are misattributing to THE ZONE OF INTEREST. In that, it presents a relinquishing of personal responsibility and how the façade of order and authority allows people to do the most evil things. These crimes happened, and looking into them, one sees how obvious the conspiracy was. I think there's value in showing that, in confronting the audience with the fact social rules and the perceived "superiority" of whiteness allowed these things to happen. It's uncomfortable, it might seem unreasonable, but it's something the audience should confront. To me, it doesn't make Mollie or the rest of the Osage Nation look stupid.

These things happen every day whether we recognize it or not, whether films tend to depict it or not, and it mostly doesn’t fit narrative sense.

I guess part of it is that I think there's value to the film's structuring as an anti-mystery, a tragedy, a repudiation of the entertaining twists of truth we're so used to seeing when Hollywood considers history. Or, perhaps more incisively, how media tends to depict evil and those who practice it. There need not be masterminds or superlatively unusual circumstances for it to manifest. In many ways, it's ingrained in how the world came to be as it is, in the colonial and capitalist forces that shaped it. An ugly and distressing view that makes the epic hard to stomach and live with.

There are no surprises or twists, nothing for us to hold on to while the tragedy reaches the point it would always reach. To be paralyzed and powerless, frustrated while watching it is suffocating - it's also part of the point. Moreover, I see challenges for the actors in this, including the three leads, though I know a lot of you disagree.

In my view, this is actual challenging art and I love that challenge. That I have to say all this in the comment section probably means I'm not a very good writer, but alas, maybe I'm not. If you’ve had the patience to read this far, thank you.

Claudio,

You are a good writer. You wrote a beautiful article, as I said before, full of passion and love.

Sometime people disagree with us - and if it comes with respect, it's ok.

I think Bening is great in "Nyad", and beyond the overdue fact. Most people here disagree.

People liked Heath Ledger in "Brokeback Mountain", and for me he's absolutely flat and inexpressive, giving a weak performance, while Gyllenhaal and Williams shine in every scene.

Some "passive performances", like almost everything the Great Joan Allen does, are extraordinary.

Personally, I think Gladstone are excellent - and should be nominated in supporting.

In leading, I think Bening and Muligam deserve to be the frontrunners- I didn't watched Stone yet.

In the end: Art is a little subjective (not entirely, just a little.

And yes, you're a good writer. 😀

I have never seen an actress more failed by her script and director than Gladstone in this picture. She does what she can but she becomes such a nonfactor in the last half of the movie and makes bizarre decisions without any insight into why. It would have helped if we spent more time with her. Choosing not to cut to her reaction to Ernest’s testimony is one of Scorsese’s strangest directing decisions.

The more I hear about ‘Scorsese’s masterful use of Lily’s expressive silence,’ the more I feel her perceived victory falls in line with Jane Wyman’s win for Johnny Belinda.

@ Stephen C: What are you talking about? The film cuts to Gladstone during DiCaprio's speech, specifically in that moment when he says he loves her. It's a very deliberate cut, demonstrative of Schoonmaker's very intentional way of cutting this film. No throwaway shots, no easy cutaways. All motivated.

@ TOM: 🙄

Juan Carlos - the film only cuts to Gladstone, briefly, after DiCaprio’s speech is done, not during it, then cuts immediately to the scene of Mollie’s final confrontation with Ernest. If the film hinges so much on Mollie’s silent interiority, I think it would have served the film to show her during the testimony of the role her husband played in her family’s murders. It certainly would have served that next scene. I think Scorsese ultimately cared a lot more about Ernest’s motivations/interiority/sense of self/regrets/ignorance, etc. than he did Mollie’s. Which is fine. It’s not new for Scorsese to focus on the criminal. I just feel like I watched a different film than everyone else when they describe Mollie’s character arc. FWIW, I thought Gladstone was pitch perfect in the first half of the film.

@ Stephen C:

As a film editor myself, I disagree.

But you do you.

Juan Carlos — it’s fine to disagree. I’m not trying to convince anyone or dilute your own passion for the editing, just stating my own opinion.

I just think that for a character’s silence to mean something, we have to actually see them being silent. Focusing that shot solely on Ernest, when we the audience had already gone through all those exact plot points and emotional beats with him throughout the movie, felt meaningless and repetitive to me. We missed a chance for a new perspective in that scene, in my opinion. That’s all.

And I don’t want to get into the gender politics of it all, but I will say that it’s a glaring blind spot in those last few scenes that the movie only cares about her reactions to Ernest’s insistence that he loves her, and not her reactions to his admission that he brutally murdered her entire immediate family.

@ Stephen C:

Again, I disagree with what you have stated, but thank you for your insight. Gave me something to think about that scene. Might examine that scene again and keep that in mind when I do a rewatch.

Your perspective and kindness is much appreciated.

We could use more of that in the comments section, tbh.