Hit Me With Your Best Shot S6.10

Hit Me With Your Best Shot S6.10

Mid Season Finale (See all the pics tonight at 11!)

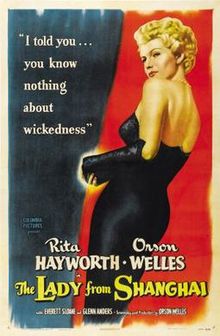

The Lady From Shanghai (1948)

Directed by Orson Welles. Cinematography by Charles Lawton Jr.

Though we're usually tasked to watch the same film for Hit Me With Your Best Shot, today for the Orson Welles Centennial, participants had their choice of three films. I chose The Lady From Shanghai (1948) largely because the only image I ever see for it online is Orson Welles seizing Rita Hayworth, both of them reflected by mirrors in the über famous "Crazy House" finale. It's one of those movie sequences you learn by osmosis just watching other movies (remember Woody Allen's take on it in Manhattan Murder Mystery?) even before you get around to this 1948 noir (Technicall IMDb says 1947 but it was released practically everywhere in 1948). Though the hall of mirrors contains roughly 50 shots that could justifiably be called "Best" it's their proximity and their dizzying accumulation of lies (all about to shatter) that really does it for me so I looked elsewhere.

The Lady From Shanghai is gorgeously uncluttered. It's as if only the basic tropes have room to exist: the femme fatale, the narrating dupe, the shadows, and the crimes. It's so self aware it even toasts its own genre halfway through...

Here's to crime!"

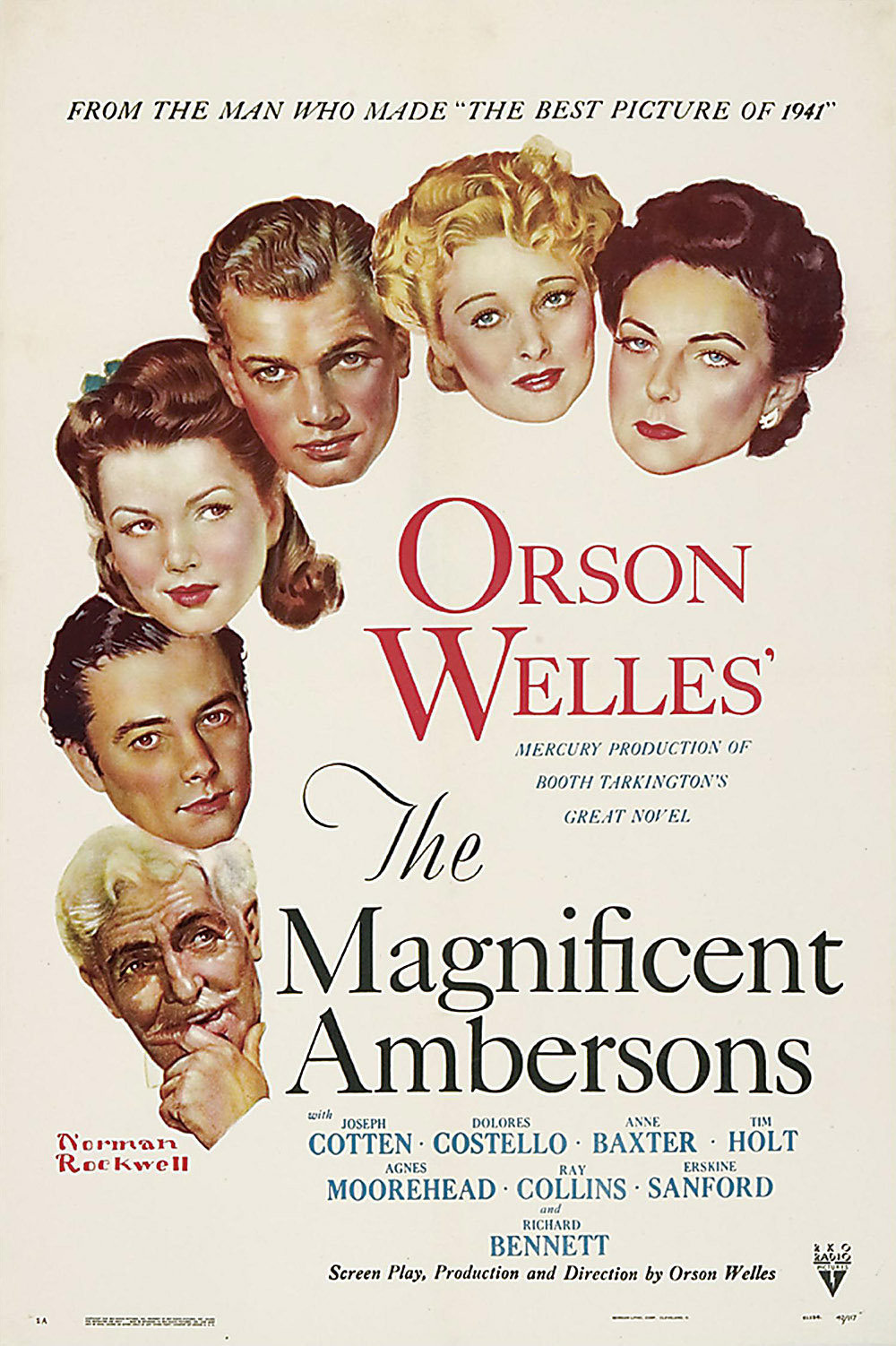

You might even call it minimalist despite the famously baroque visual finale. It was the fourth Orson Welles picture and the first to be ignored entirely by the Academy when it opened in the summer of 1948 but it won the important battle: standing the test of time.

The movie plays its hand immediately, informing you that Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth) will be Michael O'Hara's (Orson Welles) undoing. But every time you look at her, which is often since Welles and Lawton Jr give Hayworth star vehicle closeups throughout, you hope it won't be true. One very smart recurring visual motif is that Mrs Bannister is bathed in light more often than she's in shadow. She so clearly has her own key light that at the tail end of the movie's first sequence, when Welles jumps in a horse drawn carriage with her, their images seem artificially conjoined since he's so shadowy and she's so bright.

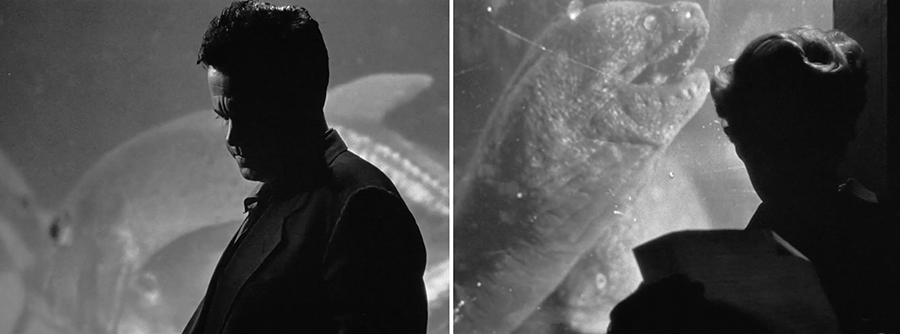

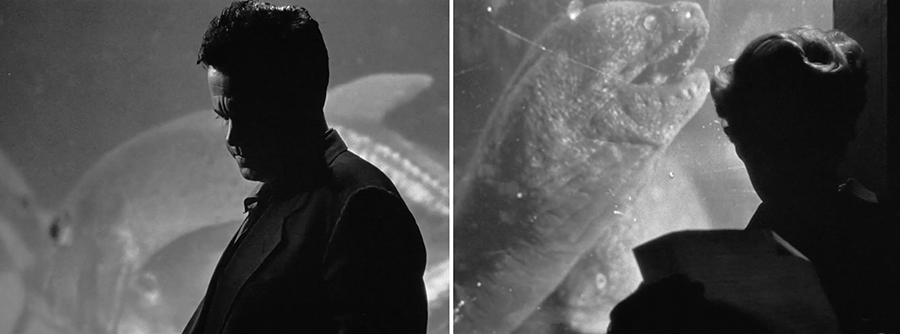

But this lighting motif is a lie, one you catch if you a) believe the narration and b) listen to the dialogue of the film's oiliest and most repulsive character who refers to the paradise around these rich sharks as a "bright guilty world." One notable exception, the one I'd select as Best Shot if I could have two conjoined images to illustrate a point, is when Elsa and O'Hara meet in an quarium. This time they're both bathed in shadows though something is very different about the shots: when O'Hara stands next to the glass they're like harmless magnified fishies; when Elsa picks a spot to stand the marine life is far more disturbing, gasping for air.

But for Best Shot I'm going minimal, and brightly lit, conveying the intoxication of Rita Hayworth. The shot below is breathtaking in its sensuality; Elsa gets the full glamour treatment, the glistening eyes and slightly parted mouth, the soft but ample lighting. But Welles doesn't rest on his co-star and lover's beauty alone. There's an impressive array of choreographed movement that keeps whiplashing the camera back to her, reclined, through lots of business with her three men and one cigarette. You're constantly aware of the relationships between the four principles. This is is not a typical triangulated affair or evil quartet but a circle with Elsa Bannister always at its center.

best shot

best shot

And since we're speaking of juxtapositions, if you pair this hypnotic sequence -- your eyes are getting heavier... You will do whatever Rita breathily implores! -- with an even more brightly lit but far less serene shot of her face in the climax, this star turn reveals itself as quite a bifurcated triumph; it's half fawning iconography (until the mask of her glamour finally drops) and half shifty performance.

By all means if you haven't seen this movie -- or any of Orson Welles's masterpieces, do.

Sunday, October 22, 2017 at 8:50PM

Sunday, October 22, 2017 at 8:50PM  Joan Fontaine's reign at the top of the Hollywood pyramid was short and intense: three out of four movies made in three out of four years netted her Oscar nominations, with a win for the second, Suspicion. We come now to the film made immediately after this golden run: the second talkie adaptation of Charlotte Brontë's 1847 classic Jane Eyre, released in the United Kingdom at the very end of 1943, but held back from the U.S. until February, 1944.

Joan Fontaine's reign at the top of the Hollywood pyramid was short and intense: three out of four movies made in three out of four years netted her Oscar nominations, with a win for the second, Suspicion. We come now to the film made immediately after this golden run: the second talkie adaptation of Charlotte Brontë's 1847 classic Jane Eyre, released in the United Kingdom at the very end of 1943, but held back from the U.S. until February, 1944.