"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

Florence's beloved Verdi sports her sensible chapeau.

Florence's beloved Verdi sports her sensible chapeau.

Florence Foster Jenkins was a woman of grand exuberance. She’s mostly remembered for her terrible voice, which I suppose is fair. It’s worth noting, however, that she didn’t exactly intend to make comedy albums. It was her irrepressible love of music that drove her to the stage, the recording studio and, by way of generations of blithe dinner parties, into the 21st century.

With that in mind, a Meryl Streep movie seems like an inevitable conclusion. Florence Foster Jenkins’s director (Stephen Frears) and screenwriter (Nicholas Martin) clearly understand both pieces of the character, her fervent fandom and her wobbly voice. In fact, they so thoroughly embrace her passion for music that they suggest it’s what killed her.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Before Streep’s version of Florence takes her final bow, she lives her musical commitment. The design team of production designer Alan Macdonald (The Queen), supervising art director Patrick Rolfe (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo) and art directors Gareth Cousins (BBC’s Jane Eyre) and Christopher Wyatt (Wuthering Heights) craft for her the most musical spaces possible without a total break from realism...

Of course, Florence herself seems determined to push that very boundary. The tableaux presented to the Verdi Club are fulfillments of fantasy. Suspended from the ceiling, the socialite silently impersonates a muse. Later, she becomes Wagner’s Brünnhilde. She stands in front of a bright and elemental backdrop, tastefully bloody corpses at her feet. The orchestra plays the Ride of the Valkyries with vigor, a musical endorsement of this charmingly absurd recreation.

After all, why should Florence obey the limits of reality? She’s an opera fan. What matters is the rush of the orchestra, the feelings that gush from the notes of the vocal line. Accordingly, Streep’s Florence is as larger-than-life as her Julia Child or her Anna Wintour. She is an icon of passion, not a citizen of the dull world that lurks outside the opera house, or the cinema.

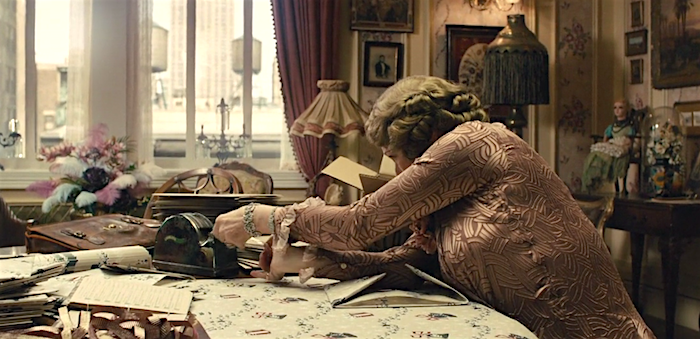

The designers, therefore, elevate her period-appropriate decor with her fanatical devotion to music. Florence’s Hotel Seymour suite is only slightly less ridiculous than the ersatz Valhalla at the Verdi Club.

There are pieces of devotional memorabilia everywhere. One wall is a showcases for Florence’s collection of composer portraits. There’s Wagner, of course, and what appear to be multiple images of Liszt. The central position is reserved for Verdi.

Out in the hall, the same composers bless the apartment with their busts. They are joined by a crowd of matryoshka dolls, an elaborate lamp, and even more portraits hanging above.

Not every relic is clear to the naked eye. The hallway also features a row of chairs in which, as husband St Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant) explains, various celebrities expired. They are, understandably, “not for practical use.”

Not an inch of wallspace is bare, no corner empty. One wall of the yellow music room features picturesque depictions of ruins, small paintings of what might be nymphs and a still life of flowers. The colors are doubled by the fruit display beneath and echoed by the roses of the wallpaper. It seems reasonable to assume that Florence is a great believer in the emotion evoked by sublime depictions of the natural world. The hills, if you will, are alive with the sound of music.

It’s easy to imagine Florence walking through her apartment, frequently stricken with sudden decorative inspirations. It’s certainly a plausible explanation for the flower and feather bouquet next to the window below, as well as the ornate doll seated in a miniature chair on the back table.

Florence’s is the exuberance of a fan who lives the art that she loves, the sumptuous musical excesses of opera. It’s no accident that the impetus for her return to singing is the Bell Song from Lakmé, an aria so extravagant that it dispenses with lyrics entirely in favor of high-flying vocal acrobatics. That same spirit runs through Florence’s apartment, her artistic career, and her joie de vivre. Every flight of fancy leads to a coloratura explosion of feathers or flowers. It’s as clear in her bathtub of potato salad as it is in her Carnegie Hall triumph.

previously on The Furniture

Tuesday, January 10, 2017 at 4:00PM

Tuesday, January 10, 2017 at 4:00PM