Best International Film: Pakistan's "In Flames" & India's "2018"

Thursday, December 7, 2023 at 5:00PM

Thursday, December 7, 2023 at 5:00PM Considering the Academy's general disinclination to honor horror cinema, it's always surprising when the genre pops up amid Best International Film submissions. This year, Pakistan is one of the brave countries that didn't let genre bias stop them from selecting a scary movie for the Oscar race. Zarrar Kahn's In Flames is the lucky flick, a Canadian-produced meditation on grief, trauma, and poisonous patriarchy bound to unnerve viewers. Neighboring nation India didn't dip their toes into nightmare cinema but sent a disaster picture that's horrifying in its own way. Juan Anthany Joseph's 2018 dramatizes a real-life catastrophe that befell the state of Kerala…

IN FLAMES, Zarrar Kahn

The artists behind In Flames wouldn't necessarily describe their film as horror. Instead, they'd be more inclined to present it as "a drama with horror beats because horror is an extension of the psychology of the character's experience." And yet, from the start, the picture welcomes the viewer into a world of shadows and strange noises echoing in the night. Through these nocturnal passages, one arrives at a home plunged in white for a burial. The family's patriarch is no more, so the women pay their respects in lace and gloomy faces, fearing the vultures already circling them. An uncle promises help to the bereaved, but his words taste insincere. And so, some inchoate sense of wrongness emanates from the screen.

That eerie feeling intensifies as the camera picks a protagonist in young Mariam, a medical student living in contemporary Pakistan. Sometime after the funeral, we catch her driving to the library when terror strikes in the form of angry men calling her a whore and throwing a brick at the car. It's a disturbing scene, like something out of a zombie story, and without overplaying his hand, director Zarrar Kahn emphasizes his character's psyche by having the film disassociate along with her. This is far from the only instance of misogynistic violence that Mariam faces, but all her attempts at seeking justice are undercut. Even though she wields her father's memory as a powerful man, an unjust system will silence the woman at every turn.

That said, neither narrative nor form is beholden to unwavering misery. Within Mariam's struggles, Kahn still finds time for the blossoming of young love and sunshine warm cinematography. Idyll manifests in an urban landscape, precipitating a romantic montage full of bubbling music and phosphene glow, exuberant and exhilarating in its defiance of strict social codes. But of course, on the margins of the joy, darkness looms, ghosts of patriarchy ready to consume Maryam, her mother, and her brother the moment an opportunity arrives. It comes in an illicit trip to the shore when the lovers' stolen moments crash on the road. Abstraction emerges in a lonely pilgrimage back home, between deaths.

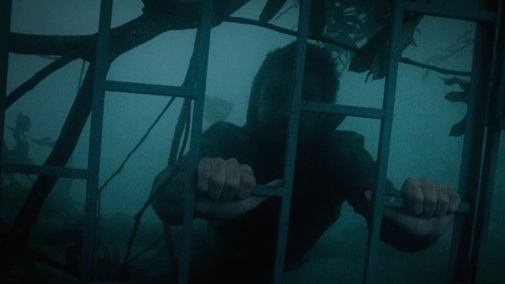

And as much as she tries to wash it off, the stain of lost life won't leave Mariam. It's an infection that starts on the periphery of her eye but grows to consume her whole vision, her complete existence. Maternal fears and an iman's advice end with Mariam imprisoned inside her home, paranoia surging out of every pore. But what's coming can't be so easily stopped, for the horror of a woman living in a society that hates her is beyond words. It's not only the student either, for her mother feels it, too. Indeed, one hour into In Flames, a perspective switch allows us to experience the ghost story through another set of eyes, coming to know Mariam's crucible as something shared with generations of women, with fearful Fariha.

Escalating frights see the masculine specters become increasingly violent, as old promises and prophetic winds invoke a purge by flaming fire. By its climax, space and time are distorted, as one walks into a derelict and enters a memory, ghostly hands wanting to drag mother and daughter into damnation. Though its characterizations are inconsistently developed, and the internal logic is often more confusing than enlightening, In Flames ends on a high note. Reaching for a ray of hope that might have seemed impossible at the start, the story of Mariam and Fariha comes to grips with faith as salvation against the unholiness of male oppression. Even when it skirts incoherence, there's a solid emotional backbone underlying the whole exercise.

2018, Jude Anthany Joseph

The disaster movie represents one of the few models of mainstream filmmaking where a collective approach to storytelling is the norm rather than an outlier. It's true across continents and industries, resulting in experiences that value a community's resilience with the same enthusiasm they do acts of individual heroism. This manifests in projects aimed at fizzy entertainment and more serious stuff. On one end of the spectrum, you find such silly stuff as that slew of star-studded pictures that were all the rage in 1970s Hollywood. On the other, you have something like 2018, where a true catastrophe serves as an opportunity to celebrate survivors and honor the dead, glorify the nation while grieving its losses.

Aptly, 2018 presents another name when its title screen finally appears 20 minutes into a two-and-a-half-hour Malayalam epic. It says "Everyone Is a Hero," a tenet maintained throughout its story of the Kerala Floods. That doesn't mean Jude Anthany Joseph is uninterested in having a set protagonist to guide the viewer into the depths of calamity. He's Anoop, a former military man still haunted by what he saw on the battlefield and the decision to lie about his health to get out of service. As played by the über-charismatic Tovino Thomas, the character's whole arc is evident from the minute he's introduced, a common happening across a film whose script's conventional to the point of contrivance.

That's not to say 2018 is narratively inept. Instead, it's almost classical in its love for archetypes and easy-to-digest morality, everything painted with broad strokes to better frame the survivalist thrills of its central action and, later, the swell of feeling as the audience is invited to share in the characters' breath of relief, their catharsis. At its best, the movie brings it all down to the value of every human life, placing as much stakes in one boy's fate as that of the region as a whole. Regarding structure, the matter is dicier, with some flashback flourishes seeming unnecessary if not detrimental to the picture's flow. Nobin Paul's fantastic score helps smooth over some transitional oddities, but it's not enough to solve the problem.

Furthermore, the picture lacks visual ingenuity as a whole. Footage before the flood almost looks digital raw, as if someone forgot to grade it in post, while the catastrophe submerges the screen in muddied grays and underlit exteriors. One recognizes the attempt at realism, but when the script and score lean so hard toward old-fashioned romanticism, the images should follow their lead. This may be because I didn't experience 2018 on the big screen, but some high-wire sequences were nearly unintelligible to the eyes. In contrast, the use of archive footage reveals a more dynamic picture, colorful despite its depicted destruction. Thankfully, the sound mix's negotiation of sensorial terror and heightened cinema is better calibrated, and the VFX work is good enough to survive the lack of photographic clarity.

In Flames is now in theaters, enjoying a limited release by XYZ Films. However, it'll struggle to get into the shortlist. 2018, on the other hand, could benefit from a renewed interest in Indian cinema that started with last year's RRR.