Robert here with my series Distant Relatives, which explores the connections between one classic and one contemporary film. This week we jump into the admittedly pointless but always fun Chaplin vs. Keaton debate and contrast it with the Pixar vs Dreamworks animation debate. The important thing is to remember that you can love all of these films and it's not a competition.

But if it were a competition (and it's not), we start with Chaplin and Pixar because they're the obvious frontrunners. By that I don't mean that they're better, but they have the name recognition, the marketing, the cultural branding. Chaplin built for himself an image that now almost a century after his first shorts, is still recognizable. Pixar meanwhile, in just over fifteen years in the feature business has introduced a slew of films and characters that have become iconic. While quality is mostly the cause, it doesn't hurt to have most of your films named after their title characters (why Nemo will always be more recognizable than Carl Fredricksberg). So, Chaplin and Pixar are both heavyweights. They share that. They also share a sense of style and innovation, a desire to elevate their genre beyond it's conventional expectations, a love of traditional arcs, and a soft spot for over-sentimentalization.

Lovelorn tramps in the future

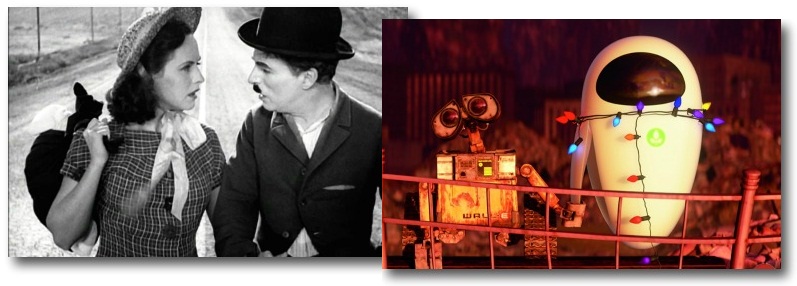

Among the Pixar canon, the best film for our Chaplin comparison is WALL•E because, well a fair portion of its marketing to the online film geek world involved the constant reminder that animators took much inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, although the connections were already pretty evident. To put it another way: you didn't have to read an article on the Chaplin/WALL•E inspiration to see it, but you probably did. WALL•E follows a hapless, lonely, poor protagonist who falls in love and must suddenly achieve something great to get the girl while simultaneously getting the girl to achieve something great. It's one of the few Pixar films that places a strong emphasis on its romantic plot, and WALL•E himself, the nearly silent, occationally prat-falling protagonist is the perfect Chaplin descendent. So WALL•E is an easy choice, but why Modern Times?

Modern Times is unique among Chaplin's films in that a unusually strong focus is placed on the source of The Tramp's discontent. In most other films, The Tramp is a generic vagrant, downtrodden for many unnamed reasons. In Modern Times, he's not a vagabond, he's a worker. His oppressor isn't whatever bully or police brute or aristocrat might be antagonizing him that scene, it's the whole out-of-control industrial complex. It's the giant face of the uncaring corporate class. Yes, it's undeniably political. And so is WALL•E. As much as Pixar attempted to quell controversy, insisting that any politics present were simply there to serve the story, there's no escaping the fact that WALL•E's oppressor is also a giant corporation that cares far less for its workers (in WALL•E's case robots) than for its image and its profits.

Romance and politics and a happy ending.

For both films controversy was unavoidable, and in both cases the filmmaker's weren't shy about subtley commenting on what they were stirring up. A scene in Modern Times where The Tramp inadvertantly leads a communist parade and ends up cast out from society was prescient in regard to Chaplin's eventual career. As for WALL•E, it's hard not to see a sly wink to that year's upcoming US presidential election in a scene where the whole of humanity decides that "blue is the new red." Yet, overtly political as they are, both films do a good job of avoiding platitudes and focusing their attention on their little man main characters whose humanities are being crushed under the threat of their brave new world. Of course, throughout it all, love prevails. Love, that great cinematic motivator, proves that our heroes are more than just cogs in a machine, and capable of doing great things; little great things in the case of The Tramp or big great things in the case of WALL•E.

This is probably the most significant thematic difference between the two films. Chaplin's Tramp wants to get the girl, but WALL•E is tasked with getting the girl and saving the world. Of course, WALL•E's plot gives the film no other choice. Perhaps it the modern mindset that demands a whole world-saving happy ending, or perhaps it was impossible to place that old trash compator WALL•E in a trash-ridden world and not expect him to exceed in the biggest scale imaginable. Either way, Chaplin's film can leave the world a mess while Pixar's cannot. Still, both films serve up a decent serving of uncertainty for their finales, emphasizing that the real important goal, the pursuit of love, has been met and the rest will somehow be okay. Sentimental yet socially conscious, Modern Times and WALL•E are brethren that aim to entertain and enlighten and propell their lovable protagonists into a satisfying future.

Other Cinematic Relatives: Meet John Doe (1941), The Apartment (1960), Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), Avatar (2009)

Wednesday, April 16, 2014 at 8:40PM

Wednesday, April 16, 2014 at 8:40PM

Anthony Mackie,

Anthony Mackie,  Charlie Chaplin,

Charlie Chaplin,  Chris Evans,

Chris Evans,  Gyllenhaalic,

Gyllenhaalic,  Tony Awards,

Tony Awards,  Tupac,

Tupac,  X-Men,

X-Men,  superheroes

superheroes