Team FYC: "Blue Jasmine" for Costume Design

Wednesday, December 11, 2013 at 10:00AM

Wednesday, December 11, 2013 at 10:00AM In the FYC series, we're spotlighting our favorite fringe contenders. Here's abstew on Blue Jasmine's threads.

When it comes to the Oscar for Best Costume Design, the Academy's aesthetic seems rather limited. They go one of two ways: Period Piece or Fantasy. Having a tendency to confuse 'Best' with 'Most' the eventual winner is often whichever is that year's most elaborate or over-the-top design (Alice in Wonderland, really?!). Contemporary set films with well-thought-out clothes that define the character tend to get overlooked in the Season End Gold Rush. Breakfast at Tiffany's, Pretty Woman, and Clueless are all victims of this crime against fashion. So, hopefully when the nominations are announced on January 16th, Cate Blanchett's inevitable Best Actress nomination for Blue Jasmine will be joined by a nomination for Suzy Benzinger's meticulously designed costumes for the Woody Allen film.

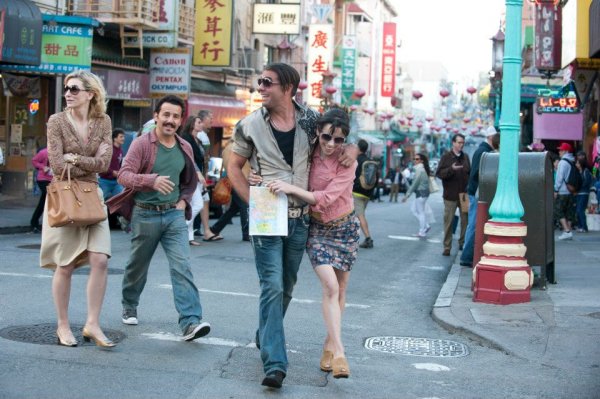

As a Park Avenue socialite, Jasmine French's life is defined by labels. Not just the one's society has placed on her - wife, mother, sister - but, more importantly, the one's that matter most to her, Designer labels - Chanel, Fendi, Louis Vuitton (Blanchett's pronunciation of the French fashion house is perfect in its pretension). In the first shot we see of her, sitting in First Class in her Chanel jacket, crisp white shirt, and strands of pearls, we immediately know who this woman is before she's even said a word. The Upper East side theater I saw the film in (next to Bloomingdale's, of course) was populated with woman all wearing a variation of the uniform. So, it makes sense that when Jasmine's world unravels after the downfall of her corrupt husband, the labels are all she has to cling to. Upon meeting her sister Ginger's boyfriend Chili and his friend, she clutches that highest of all status symbols, the Hermès Birkin bag, as if her life depends on it. Without it she'd be just as low-class as they are.

And yet, as the film progresses, you begin to see something a woman in her position would never be caught doing in public - repeating outfits. There's that Chanel jacket again paired with a different shirt. Jasmine's fall from grace has forced her to be thrifty, mixing and matching clothes like a regular person. And she's soon confronted with something she thought she'd never have to wear in her life: hospital scrubs at a dentist office. (Her sister Ginger's job as a grocery store checkout girl, requires her to wear a similarly hideous smock.) The juxtaposition of how different the two are is clearly illustrated by the women's clothes. Ginger, all short denim skirts and platform espadrilles, is everything Jasmine has spent her whole life avoiding. Benzinger expresses so much about these character's through what they're wearing. The costumes are more than just clothes, but an essential element of the storytelling.

some previous FYCs... Mud | Stories We Tell | In a World... | Short Term 12 | The Great Gatsby | Nebraska | Lawrence Anyways | World War Z | The World's End | The Conjuring | Aint Them Bodies Saints

Blue Jasmine,

Blue Jasmine,  Costume Design,

Costume Design,  FYC,

FYC,  Oscars (13)

Oscars (13)