In "The Honoraries" we're looking at the careers of this year's Honorary Oscar recipients including Hayao Miyazaki. Here's Manuel on an animated gem...

Spirited Away, Ponyo, Howl’s Moving Castle and My Neighbor Totoro all wowed me on first viewing. In that sense, I agree with Tim, to choose just one Miyazaki is close to impossible. I know it will date me (more on that in a minute), but while I love what 3D animation can (and has!) done, to me, there’s nothing more exhilarating than traditional, hand-drawn animation. This may be because I come from a household where animation is the family business (little do people know that my mother owns the longest-running animation studio in Colombia) so I pretty much grew up around animators, scanners, and spent many a weekend waiting for a certain scene or episode to finish ‘rendering’ before we could head home, while perusing the “Art of” books that lined the shelves at the office.

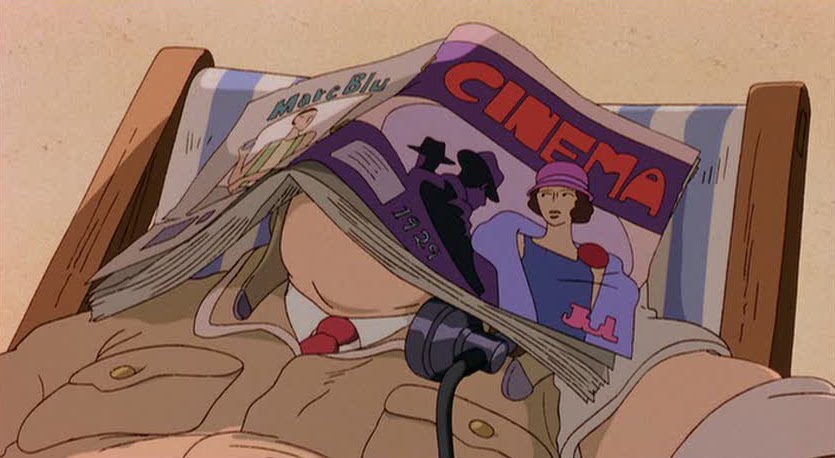

So to commemorate Miyazaki’s Honorary Oscar I thought I’d treat myself and look at one of his films I’d never seen before. I ended up choosing Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind which turned (like yours truly) 30 this year and boy is it a beauty.

Nausicaä soars on the back of its eponymous protagonist. Catching it in 2014, it’s hard to gage whetherNausicaä was ahead of its time or whether pop culture has been slowly feeling its influence since its premiere. Probably both. I mean, here we have an environmentally-conscious plot about a strong-willed and empathetic teenage girl set in a post-apocalyptic world who refuses to engage in the needless killing and destruction that adults around her seem committed to as a way to survive; hard to deny that that sounds familiar no? But to say that Nausicaä is a precursor to Katniss Everdeen (and her fellow YA kickass dystopian gals) is to sell Miyazaki’s film and protagonist short. This is not only because, as Tim noted last week, Miyazaki is less interested in ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys’ (there’s no President Snow and The Capitol to hate here), but because his Nausicaä wouldn’t be caught dead in a love triangle, sadly still a staple whenever we’re granted a female-led action adventure franchise. Indeed, Nausicaä may be an even greater feminist film than that dystopian trilogy for the way it presents its protagonist’s strengths as both born out of but not tethered to her own gender.

Nausicaä, attuned to the natural world around her (including the seemingly hostile ‘toxic jungle’, home of the dangerously angered Ohm), spends the entire movie presenting empathy as her strongest asset, even when this is constantly demeaned by those around her as mere naïveté. In that, she seems both a throwback as well as a novel protagonist. It may seem outmoded to praise a film for playing into cultural tropes about the connection between women and the earth but Miyazaki is keen to position Nausicaä’s intuition as a source of strength not nearly as incompatible with her physical prowess as we might think. At a critical moment, she’s so blinded by grief and rage (so overwhelmed with feelings) that she lashes out and knocks many a soldier down. A scene that might normally lead to a lecture about “controlling one’s anger” (because it leads to the dark side, remember?) instead quickly taps instead into Nausicaä’s own loyalty and affinity for her people, getting her to privilege pragmatism over her own blinding rage. But it is also that ability to feel and empathize with those most unlike her that ends up saving the day. Like I said, it’s both oddly quaint but also quietly transgressive.

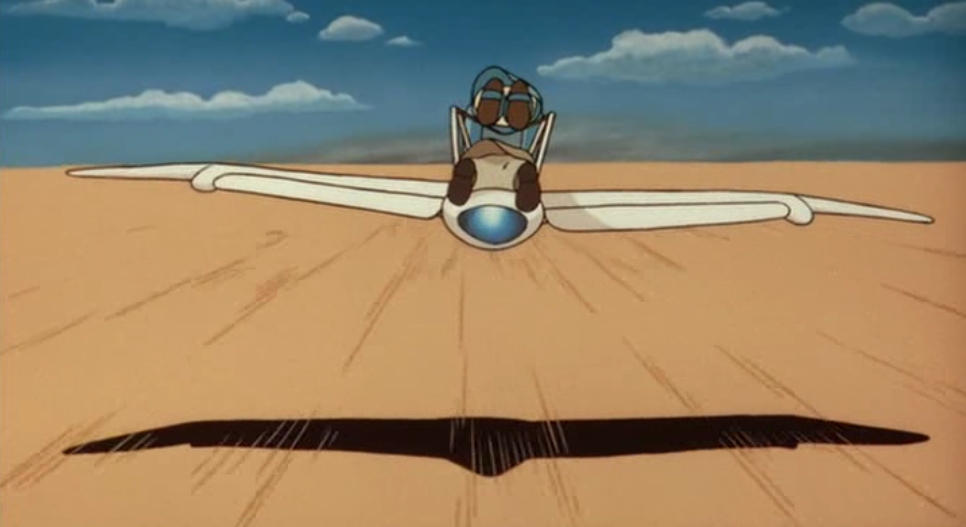

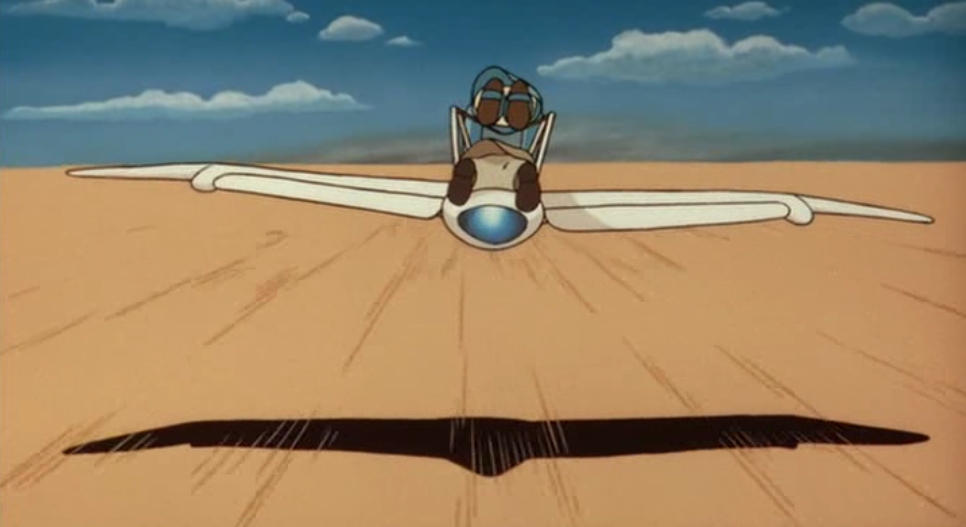

It helps that this type of gender politics becomes a part of Miyazaki’s storytelling fabric rather than its central thread. The film is a classic because it is both a thrill-ride as well as a meditation on mankind’s relationship with nature; it’s an entertaining adventure that doesn’t shy away from Big Themes, it is surprisingly rich in world-building without ever feeling bogged down in exposition; it is kinetic even in quiet moments of reflection; it is beautiful in its simplicity, Miyazaki’s clean lines equally capable of sketching an in-flight action set-piece as well as an almost-forgotten tender childhood memory.

This is all a way of saying that if you haven’t sought Miyazaki’s work, you should do yourself a favor and watch a clear example “they don’t make ‘em like they used to, but also no one ever did ’em like this anyway.”

Previously in The Honoraries: Maureen O'Hara, Jean-Claude Carrière, and Harry Belafonte

Sunday, November 9, 2014 at 1:40AM

Sunday, November 9, 2014 at 1:40AM