Team FYC: The Homesman for Cinematography

Tuesday, December 2, 2014 at 12:01PM

Tuesday, December 2, 2014 at 12:01PM Editor's Note: For the next ten days or so as awards season heats up, we'll be featuring individual Team Experience FYC's for various longshots in the Oscar race. We'll never repeat a film or a category so we hope you enjoy the variety of picks. And if you're lucky enough to be an AMPAS, HFPA, SAG, Critics Group voter, take note! Here's Manuel to kick things off.

Rodrigo Prieto is one of the best cinematographers around. From the gritty urban landscapes of Amores Perros and the color-coded visual triptych that is Babel to the painterly tableaus of Frida and the kinetic Iranian vistas of Argo, Prieto has been slowly amassing quite the filmography, working with the likes of Alejandro González Iñarritú, Spike Lee, Martin Scorsese, Pedro Almodóvar, Oliver Stone, and Ang Lee. It was the first collaboration with that two-time Academy Award winning director that netted Prieto his first Oscar nomination for capturing the breathtaking mountains that shepherded the tragic Western romance of Jack Twist and Ennis del Mar in Brokeback Mountain.

He’s back in contention this year for another twist on the Western with Tommy Lee Jones’ The Homesman. The film focuses on Mary Bee Cuddy (Hilary Swank) and George Briggs (Jones) as they make their way from Nebraska to Iowa in hopes of delivering three unstable women to the care of Altha Carter (Meryl Streep) whose husband runs a church that cares for the mentally ill.

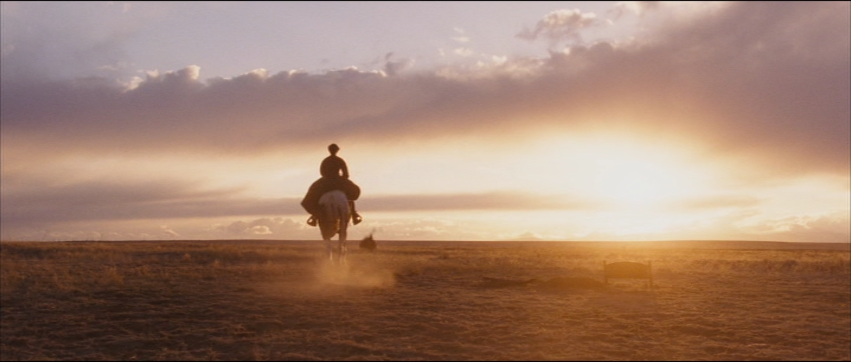

A patient and meditative film, The Homesman showcases Prieto’s great gift for making (in this case mid-) Western landscapes look sublime in the Kantian sense of the word. The barren lands Cuddy and Briggs traverse are grand, vast and majestic; “nature considered in an aesthetic judgment as might that has no dominion over us" as Kant would say. Much of The Homesman depends on the awe-inspiring and terrifying notion of that ever-receding horizon, at once limitless and infinite; promising evermore possibility while denying ever attaining it. In The Homesman, nature is both desolate and beautiful, something Prieto’s endless painterly frames evoke throughout Jones’s film. But while it’d be easy to attribute Prieto’s accomplishments to capturing the natural beauty of the Nebraskan wilderness, what struck me about Prieto’s lensing is the way his static frames both boxed these characters with a relentless indifference that indexed the harsh wilderness around them while also lighting them with a warmth that honed in on where the film’s empathy for the five travellers lies.

This is nowhere more apparent than in the way Prieto recycles seemingly clichéd images of a silhouetted lonely horse-riding figure lit by a brazen, fiery light: man framed against a godforsaken world. They’re two small moments that show Briggs and Cuddy succeeding over man and nature alike; both beautifully-lit and framed by Prieto, making use of an ever-receding natural light in one and of a blazing fire in the other. They’re striking, yes, but they also beautifully illuminate these characters’ resilience even as they’re being swallowed whole by the wilderness around them.

Can Nebraska make it two in a row in the cinematography category, after Phedon Papamichael’s nomination last year? The big push for Jones’s film seems to be in the Best Actress category, but I’m hoping that as voters queue this up for Swank’s wonderfully realized performance, they’ll also give props to Prieto, who’s overdue for a return trip to the Dolby.