Robert here, with my series Distant Relatives, where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through a common theme and ask what their similarities and differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema. This week since both films deal with a twist ending, be warned there are definitely SPOILERS AHEAD

Madness

Audiences don’t much like engaging with a film, its characters, its plot and anticipating its outcome for two hours only to be told that the entire thing was untrue, a dream, the story of a crazy man, an elaborate roleplay. The two films we’re looking at today, though made ninety years apart do that exact thing. Clearly this is a cinematic convention that has stood the test of time.

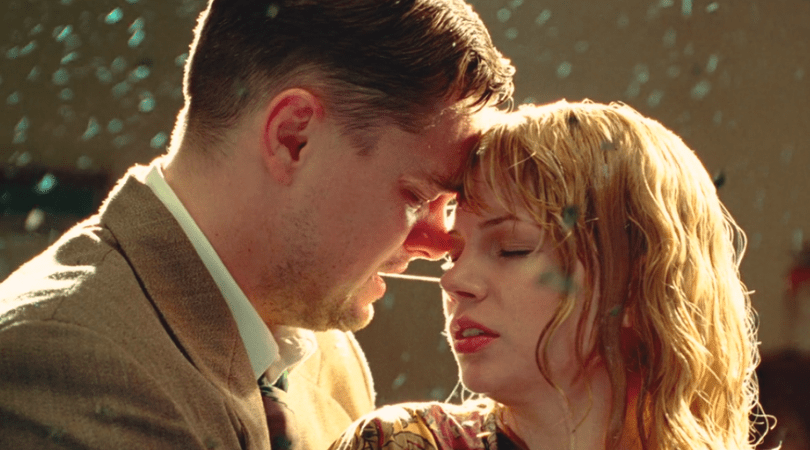

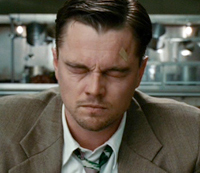

In the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a young man named Francis relates the story of a visiting carnival which brings the evil Dr. Caligari and his somnambulist slave to town. After a series of strange murders and the kidnapping of the young man’s betrothed Jane, Francis leads a posse and discovers that, surprise surprise, Dr. Caligari is the mad director of an asylum, and that his catatonic servant are behind it all. Shutter Island follows two U.S. Marshalls, Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his new partner Chuck, sent to a hospital for the criminally insane to investigate a disappearance. As their investigation goes deeper and deeper Teddy begins to suspect a deeper plot involving the hospital’s head psychiatrist, the disappeared Rachel Solondo and Andrew Laeddis, the man who killed his wife.

Unreliable narrators

Now for the twist. If you didn’t see it coming, both of our protagonists are in fact patients in their respective mental facilities. Francis has made up his entire story. Jane and the somnambulist are fellow patients. Dr. Calirgari is in fact the good director of the asylum. Teddy meanwhile isn’t Teddy at all. He is Andrew Laeddis. He killed his own wife. The entire investigation is a ruse attempting to jar him back into reality. It doesn’t quite work.

You’d be forgiven for seeing both twist endings coming for miles. Both films feature stories that become increasingly fantastic and highly expressionist production design that seems to be peace with the reality of the film at first, but eventually we wonder. Yet I’m not sure that the purpose of these films is a cheap trick twist. We logically recognize that films are fake, actors and props on a set. Yet we accept it as a reality that plays beyond the limits of the film. We consider pasts and futures for characters, motivations, inner thoughts. There’s something uncomfortable about movies that tell us explicitly that they’re fake.

The mind’s eye

The significant difference between these two movies may be the process by which they do this. Shutter Island makes little effort to cover up the fact that the “surprise” is coming. This in turn turned off a lot of viewers who anticipated the reveal, and took the falsehood of what they were witnessing as a sign that their emotional involvement was for naught. It’s an understandable reaction. Who wants to put their time and emotional effort into something untrue? The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari strings the audience along with more determination. The reveal that the entire plot is the invention of Francis is more likely to be a surprise and more likely to be received with delight (though this isn’t always the case).

Yet, as the film that spends more time winking at the audience with it’s own artificiality, Shutter Island contains more reality than Dr. Caligari. The events (or at least most of the events) in Shutter Island actually happen. It’s simply the perception of Marshall Teddy that is false, leaving us less clear as to what plot points his mind has manufactured and which are objective reality than Francis’s tale which is entirely concocted and untrue. Both of the protagonists in these stories create realities where they are heroes instead of madmen, and thus both lean toward a question asked frequently in such fantasy films (and DiCaprio’s other movie of 2010): Is a pleasant fantasy better than a troubling reality? Is it really wrong if we don’t know the difference?

So too can it be said of the movies. We allow ourselves to experience reality vicariously through characters we know are false but don’t want to believe are false. Teddy and Francis would rather be great than recognize that they are in fact powerless, ordinary, and flawed. When their films admit that they are in fact all those things, are we vicariously forced to admit that we are too?

Wednesday, February 19, 2020 at 3:56PM

Wednesday, February 19, 2020 at 3:56PM