Whiplash Screenplay Drama (Plus: My Personal Ballot)

Tuesday, January 6, 2015 at 8:50PM

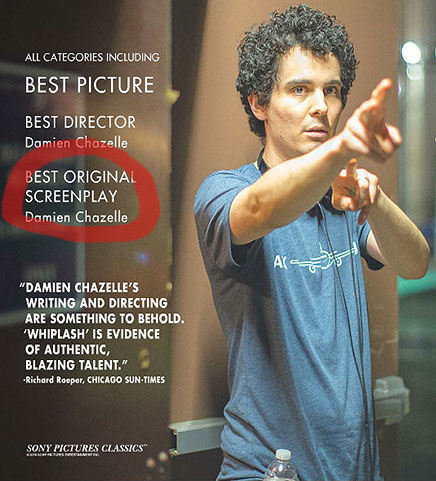

Tuesday, January 6, 2015 at 8:50PM  This can't be good news for Whiplash by way of splintered votes. Mark Harris, who is married to an Academy Award nominated writer remember, reported on Grantland that on the e-ballot reminder list Whiplash is officially considered an Adapted Screenplay by the Academy. The film's campaign always listed it as an Original Screenplay (see FYC ad left). The confusion, as also detailed on Deadline, stems from the Sundance winning short of the same name, also made by Damien Chazelle and starring J.K. Simmons. The short, according to the team, was made solely to get the feature funded. So if anything the short is an Adaptation of the feature which was made later if you will.

This can't be good news for Whiplash by way of splintered votes. Mark Harris, who is married to an Academy Award nominated writer remember, reported on Grantland that on the e-ballot reminder list Whiplash is officially considered an Adapted Screenplay by the Academy. The film's campaign always listed it as an Original Screenplay (see FYC ad left). The confusion, as also detailed on Deadline, stems from the Sundance winning short of the same name, also made by Damien Chazelle and starring J.K. Simmons. The short, according to the team, was made solely to get the feature funded. So if anything the short is an Adaptation of the feature which was made later if you will.

But the Academy rules on this are ever blurry. And technically they aren't "rules". You can vote for anything you'd like after all on your paper ballot (where this isn't a "pulldown menu" of course) but if half of its fans vote for it in Original and half in Adapted it's simple math (if math can ever be simple in preferential ballots) that it's probably not going to get nominated.

[Sidebar: The Writers Guild of America announces its nominees tomorrow but they have such strict rules about who is eligible that many well written films each year are disqualified so it's rarely a very correlative award in terms of the Oscar race. Not that there's anything wrong with that. Better more movies celebrated than fewer.]

This seems as good a time as any to announce my own ballot for Best Screenplay(s) which includes some surefire nominees (like Gone Girl) some absolutely deserving but sure not-to-be Oscar nominated screenplays like Pride, Force Majeure (original) and some oddities like The Babadook (which I put in Adapted even though it's considered Original by many because it is inspired by derived from (whatever) this earlier embryonic short... also by the wonderfully talented Jennifer Kent (who we recently spoke to).

Monster - Jennifer Kent from Jennifer Kent on Vimeo.

...unlike the Whiplash situation where it's just the same thing. Only the short is yanked from the future feature. Categories? What are they good for!? ;)

Nomination announcements have now been made in Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Art Direction for this site's annual celebratory jamboree, the Film Bitch Awards. Now in its (gulp) 15th year.